MONETARY RETROSPECT

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT As the year closes it is pertinent to ask ourselves, avoiding any wishful thinking, .exactly what has been the financial lesson of 1958. The romanticists would reply that Great Britain had re- covered its financial feet through hard work, restraint and sound finance, dear money and the credit squeeze having done their job so thoroughly that the Chan-

, cellor was able to start re-expand- ing in the last quarter of the year. The proof of this success story, they say, is to be found in a strong near-convertible £, a rise of over $1,000 million in the gold and dollar reserves and the record surplus on our international account of over £500 million. But was the cause of this effect really as noble as they imagine?

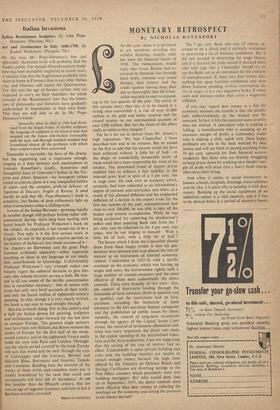

Far be it for me to detract from Mr. Amory's high reputation. 'My best Chancellor' I have described him and so he remains. But he would be the first to add that his success could not have been achieved without 'a little bit of luck'—in the shape of wonderfully favourable terms of trade which have been responsible for most of his surplus. The downward trend of import. prices enabled him to achieve a fair stability in the internal price level in spite of a 4 per cent. rise in wage rates. He took over an economy which, certainly, had been subjected to an extraordinary degree of restraint and restriction, and when, as a result of this planned deflation and the unplanned deflation of a decline in the export trade for the first ten months of the year, unemployment had risen to over 500,000, he was able to take off the brakes and resume re-expansion. While he was being acclaimed for endorsing his predecessor's policy and then reducing Bank Tate from the 7 per cent. rate he inherited to the 4 per cent. rate today, was he not singing to himself: 'With a little bit of luck, with a little bit of luck'?

The lesson which I think the Chancellor should draw from these happy events is that his pre- decessor over-stressed and over-played the rate of interest as an instrument of internal economic control. Confronted in 1955-56 with a terrific overload on the economy, which was forcing up wages and costs, the Government rightly. took a large number of counter-measures and the most effective of them were undoubtedly the direct controls. These were broadly of two sorts : first, the control of short-term lending through the limitation of bank advances (both in quantity and in quality), and the restrictions laid on hire- purchase, including the limitation of bank advances to the hire-purchase finance' companies and the prohibition of public issues by them; secondly; the control of long-term investment through the agency of 'the Capital Issues Com- mittee, the removal of investment allowances and, what was more important, the direct cuts made in the capital spending of the nationalised indus- tries and the local authorities. I am not suggesting that the raising of the rate of interest had no effect. Undoubtedly it upset private building and even now the building societies are unable to attract enough money because the high rates Offered by the Treasury on Defence Bonds and Savings Certificates are diverting savings to the Post Office counters which previously went into building mortgages. But who would deny that up to September, 1957, the direct controls were more effective than dear money in reducing the overload on the economy and easing the pressure in the labour market?

The 7 per cent. Bank rate was, of course, in- tended to be a shock 'and it certainly succeeded in destroying a lot of business confidence. But it did not succeed in destroying the wage claims, and if it shocked the trade unions it shocked them into wild rage that a Chancellor should try to use the Bank rate as an instrument for the creation of unemployment. If, then, very dear money does nothing but upset business confidence and slow down business spending without interrupting the rise in wages, it is a very expensive brake. It raises costs and worsens rather than cures a wage-cost inflation.

If you may regard dear money as a fine for economic excesses the trouble is that the penalty falls indiscriminately on the wicked and the innocent. In fact, it hits the innocent more severely than the wicked. A speculator who is making a 'killing,' a manufacturer who is scooping up an excessive margin of profit, a commodity trader who is making a slick, quick turn, these happy profiteers are not in the least worried by dear money and will not blink at paying anything from 10 per cent. upwards for their financial accom- modation. But those who are bravely struggling to keep prices down by working on a slender mar- gin of profit will often find a heavy bank charge takes away their living.

And when it comes to social investment in houses, schools, hospitals, drainage, water schemes and the like, it is plain silly to penalise it with dear money. Building up ,the 'social equipment of an industrial nation is a vital necessity and if it has to be slowed down in a period of excessive boom

it can be cut by direct action—by directives of the Government to the heads of the nationalised industries and to the local authorities. There is no point in adding to the costs of this social invest- ment by raising the rate of interest as a sort of penalty or fine on the planners.

This raises the question whether there should not be two rates of interest—one for social invest- ment and one for commercial. The latter can be determined by the market; the former can be fixed by the Treasury. The case of the New Towns sug- gests that there is a strong case for this differentia- tion. The building of the New Towns was the finest social investment the Labour Government ever undertook, and it could be said that it was financing them through the forced savings arising out of huge Budget surpluses. Why, then, should the Treasury increase the cost of this vast investment, requiring hundreds of millions of pounds, by rais- ing borrowing rates against itself? I have before me the borrowing rates paid by one Development Corporation as an agent of the Treasury since its inception. Sixteen changes have been made. At the start it was paying 3 per cent. At the beginning of 1955 it was charged 4 per cent. and then by successive increases the rate went up to 6 per cent. on September 30, 1957. An extra 3 per cent. on a £2,000 house puts up the rent by over 20s. a week. The Development Corporation is saddled by the Treasury with a senseless overcharge for borrowing what it was told to do—by the Treasury.

When Mr. Amory is meditating on these things before his log fire this season I hope he will make a New Year's resolution to sweep away the non- sense part of the monetary ritual of our financial system.

(Custos is on holiday)'

Previous page

Previous page