Ngaio Marsh

Harriet Waugh

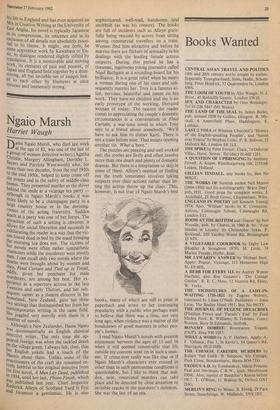

Dame Ngaio Marsh, who died last week at the age of 82, was one of the last of a group of women detective writers (Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, Dorothy L. Sayers and Patricia Wentworth) who, for More than two decades, from the mid 1930s to the mid 1950s, helped to keep crime off the streets and in the safety of middle-class homes. They presented murder as the shiver behind the smile at a vicarage tea party although in Ngaio Marsh's books it was more likely to be a champagne party in a large country house or in the dressing- rooms of the acting fraternity. Sudden death at a party was one of her fortes. The attraction of such a setting is obvious: it allows for social liberation and succeeds in exhilarating the reader in a way that the vic- tim found dead in bed by the maid bringing her morning tea does not. The victims of ner novels were often rather sympathetic characters while the murderers were mostly en. I can recall only two novels where the deaths were brought about by women and they, Final Curtain and Tied up in Tinsel, Oddly, given her penchant for male Murderers, are among her best. Her ex- perience as a repertory actress in the late Twenties and early Thirties, and her sub- sequent career as a theatre director in her homeland, New Zealand, gave her these two settings that distinguished her from her contemporaries writing in the same field. She juggled very merrily with them in a number of novels. Although a New Zealander, Dame Ngaio Was quintessentially an English classical detective writer. The only time she ap- peared foreign was when she tackled death on the village green. I always felt, then, that her English yokels had a touch of the Maoris about them. Unlike some of the practitioners of the craft she remained en- tirely faithful to her original detective from the first novel, A Man Lay Dead, published In 1934, until her last, Photo Finish, which w„as published last year. Chief Inspector Koderick Alleyn of Scotland Yard is first and foremost a gentleman. He is also sophisticated, well-read, handsome, 'and snobbish (as was his creator). The books are full of incidents such as Alleyn grate- fully being rescued by actors from sitting among commercial travellers on a train. Women find him attractive and before he marries there are flickers of sensuality in his dealings with the leading female actress suspects. During this period he has a tiresome, ingenuous young journalist called Nigel Bathgate as a sounding-board for his brilliance. It is a great relief when he meets a woman during one of his cases and sub- sequently marries her. Troy is a famous ar- tist, nervous, beautiful and intent on her work. They have no children and she is an early prototype of the working, liberated woman of today. The nearest the reader comes to appreciating the couple's domestic circumstances is a conversation in Final Curtain, a war-time novel in which Troy says to a friend about somebody, 'We'll have to ask him to dinner Katti. There is not a train before nine. That means opening another tin. What a bore.'

The puzzles are pleasing and well worked out; the stories are lively and often involve more than one death and plenty of domestic dramas. But there is a temptation to skip in some of them. Alleyn's method of finding out the truth sometimes involves taking suspects over their actions rather than let- ting the action throw up the clues. This, however, is not true of Ngaio Marsh's best

books, many of which are still in print in paperback and attest to her continuing popularity with a public who perhaps want to believe that there was a time, not very long ago, when violence was a matter of the breakdown of good manners in other peo- ple's homes.

I read Ngaio Marsh's novels with greatest enjoyment between the ages of 13 and 16 when it still seemed conceivable that life outside my convent went on in such a man- ner. If crime ever really was like that or if Ngaio Marsh's characters ever existed in other than in such pantomime conditions is questionable, but I like to think that sud- den, neat, emotional murders can take place and be detected by close attention to invisible cracks in the murderer's defences. She was the last of an era.

Previous page

Previous page