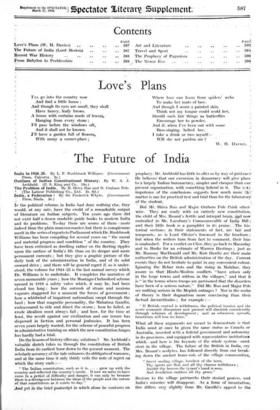

The Future of India

The Problem of India. By B. Shiva Rao and D. Grahain Pole.

• (TheLabour Publishing Co., Ltd. 2s. 6d.) • Press, Simla.' 3s.)

IF the political reforms in India had done nothing else, they would, at any rate, have the credit of a remarkable output of literature on Indian subjects. Ten years ago there- did not exist half a dozen readable guide books to modern India and its problems. To-day there are scores of them—more indeed than the plain man can master, but there is conspiCuous merit in the series of reports to Parliament which Dr. Rushbrook Williams has been compiling for several years on " the moral and material progress and condition" of the country. They have been criticized as dwelling rather on the fleeting ripples upon the surface of India's life than on its deeper and more permanent currents; but they give a graphic picture of the daily task of the administration in India, and of its solid onward drive ; and there will be general regret if, as is under- stood, the volume for 1924-25 is the last annual survey which Dr. Williams is to undertake. It completes the narrative of seven memorable years ; how the Montagu-Chelmsford scheme opened in 1918 a safety valve which, it may be, had been closed too long ; how the outrush of steam and noxious vapours staggered for a moment the forces of government ; how a whirlwind of impatient nationalism swept through the land ; how that magnetic personality, the Mahatma Gandhi, endeavoured to ride and direct the storm ; how he failed, as crude idealisM must always fail ; and how, for the time at least, the revolt against our civilization and our tenure has dispersed in faction and personal jealousies. It has been seven years largely wasted, for the scheme of peaceful progress in administrative training on which the new constitution hinges has hardly had a trial. Do the lessons of history offer any solutions ? Mr. Archbold's valuable Sketch takes us through the constitution of British India from its earliest hour down to the present moment., The Scholarly accuracy of the tale enhances its obbligato of romance, and at the same time it only thinly veils the note of regret on which the story endi :— " The Indian constitution, such as it is,.. . . grew up with the country and reflected .the country's needs. If now we seem to have come to a period of difficulty and danger, it can only be because there is a divergence between the ideas of the people and the nature of that constitution as it exists to-day."

And yet in the brief postscript in which alone he ventures on

prophecy, Mr. Archbold has little to offer us by way of guidance He believes' that our excursion in democracy will give place toalargely'Indian bureaucracy, simpler and cheaper than our. present organization, with something federal in it. The vc ry impotence of the conclusions .suggeSts how much more th."' matter is one for practical test and trial than for the laboratory

of the student.

But M. Shiva Rao and Major Graham Pole think other-- wise. They are ready with an entirely new constitution, the child of Mrs. Besant's fertile and intrepid brain, .4.94 now embodied in Mr. Lansbury's Commonwealth of India Bill ; and their little book is a pamphlet in its praise. . The .his- torical sections, in 'their statements -of fact, are fail: and temperate, as is Lord Olivier's foreword to the brochure; but when the writers turn from fact to comment, their bias is unabashed. For a verdict on Clive, they go back to Macaulay and to Burke for an estimate of Warren Hastings ; just as Mr. Ramsay MacDonald and Mr. KeirHardie are their main authorities on the British administration of the day. Current events they do not hesitate to paint in any convenient colour. Ignoring the Behar riots and the rising in Malabar, they assure us that Hindu-Moslem conflicts "have arisen only in the large towns and seldom in the villages," and that it is " in the towns where troops are garrisoned that the disorders have been of a serious nature." Did Mr. Rao and Major Pole see nothing serious in the Moplah outrages ? Nor in the realm of theory is their dogmatism more convincing than their

factual inexactitudes ; for example :-

" If British control is withdrawn, the political tension and the acute economic discontent now present will diminish considerably through' 'schemes of development ; and as education spreads, fanaticism will lose its force.'

What all these arguments are meant to demonstrate is that India must at once be given the same status as Canada or Australia, invested with a federal government and autonomy in its provinces, and equipped with representative institutions which—and here is the keynote of the whole system---must start in the village. The failure of the British in India, cry Mrs. Besant's acolytes, has followed directly from our break- ing down the ancient home-rule of the village communities,

" Sweet.smiling village, loveliest of the lawn, Thy sports are fled, and all thy charms withdrawn ; Amidst thy bowers the tyrant's hand is seen, And desolation saddens all thy green."

Restore to the village patriarchs their storied powers, and India's -miseries will disappear. As a form of incantation, this differs very slightly from Mr. Gandhi's appeal to the spinning wheel for India's salvation. Both conceptions invoke archaic methods which have atrophied long ago through the natural proceSses of the country's develop- ment. It would, of course, be an excellent thing if the village communities would. manage their own local affairs, but it would still leave us a long way from 'solving the bigger prOblemS, and the conduct of Ind ia's leaderS during the last Seven years has been poor evidence of theii capacity to shoulder Dominion.. status and its responsibilities.

Federation is one of the catchwords much in vogue among those who would fain take up Lord Birkenhead's challenge to produce' a better constitution than Parliament gave them in 1919. Like village self-government, it is supposed to hold the secret of some Magic short-cut to Home Rule. The Government of India did well to commission Sir Frederick Whyte to Study-the federal systems of the world, and to advise how far their principles are applicable to existing conditions in India. His analysis of the seven best types of modern federalism, from Switzerland to America, finds plenty of points at which India could profit from their experience ; and Sir Frederick improves the occa- sion by dwelling on the atmosphere of unity, nationality and a conscious dual pairiotisni in which alone a federal system can breathe. If he had' stopped there, his report would 'have lost none of its Value. But he is curiously insistent on a complaint that nobody—neither his Majesty's Government, nor the Government of India, not Mr. Montagu, nor Lionel Cui-tis-envisziged.the federal implications of the new regime. Even if this were true, what is there to complain of ? Those who worked at the new constitution were 'cleviSing not a federal system for existing autonomous units, but the begin; nings of a political life which might in time---or might not-- blossOrri into federation. But the complaint is baseless. The whole conception of federation is rooted in a division of functions between the central and the provincial powers, and such a division was of the essence of the Montagu-Chelmsford scheme throughout. How carefully the ground which Sir Frederick treats as Virgin soil was traversed in the long dis- cussions of 1917-19 is apparent from many passages in Mr. Lionel Curtis's Dyarchy, which Sir Frederick ignores. This, however, is by the way. Federation in India may come some day, not necessarily a union of the artificial geographical units which compose the existing provinces, but an association oii'the one hand of administrative areas determined on closer affinities of local patriotism, and on the other of the self- governing Indian States. It will be a federation of a type , unique in political experience, and held together by a cement . which has still to be extracted from the Indian soil ; but there is no reason. to despair of its accomplishment. To labour the idea at present, however, is sheer waste of time ; none of the essentials are ready. It is worse ; because the cry for federa- tion is a symptom of that pathetic devotion to the arid me- chanism of politics rather than to the spirit of humanity which makes political progress a reality. In Indian life and character there is an infinity of good ; and the particular type of con- stitution which will best evoke and employ it will ultimately be found. Meanwhile the wrangling over forms must cease. The world looks to the Indian leaders to get on with the business of government, and of government for the general . good of the People..

MESTON.

Previous page

Previous page