Necessary to know in order to see

John Steer

MANTEGNA: WITH A COMPLETE CATALOGUE OF THE PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND PRINTS by Ronald Lightbown

Phaidon-Christie's £60

How difficult it is to write popular art history! In other subjects, English Litera- ture, for example, or History proper, there is a wealth of writing which, as well as being more than respectable as scholarship is also, by intention, accessible to the general reader. In the History of Art, there is almost none. Some of the Thames and Hudson World of Art series, Gombrich's Story of Art, the writings on art of Anita Brookner and Michael Levey, both of them incidentally novelists, fit this bill. But how little else!

Mantegna is not an easy artist or one who naturally appeals to modern taste. All that learning: the supposed sycophancy of 46 voluntarily chosen years at a princely court: the immense amount of detail in his works, which require them to be read as well as experienced: all these things de- mand exegesis and explanation. With him, it is, to an unusual degree, necessary to know in order to see and enjoy.

A new book on Mantegna was then needed: a book surely to appeal to the intelligent many as well as the specialist few, a book to be read by anyone in- terested in the artist and his art. How far does this book do the job?

Lightbown has a great gift for descrip- tion and in this he and his artist are well matched. His book is long — 233 pages of text in double columns apart from the catalogue — and much of it is a close visual analysis of what actually goes on in Man- tegna's works. At such length this can be daunting, but for those with patience it is also, detail by detail, rewarding, simply because it makes one look with new eyes and new attention at the works themselves.

Take for example a passage on the Ecce Homo in Copenhagen in which he writes in close focus of the minute view of the burial cave at the back of the picture. Mantegna has allowed us to see through it to a narrow band of sunlight 'beyond the darkness of the cave' against which the tiny figure of a man is silhouetted. It is this kind of subtle observation of light, both precise and poetic, which, after the colder heroics of his earlier works, makes Mantegna's late paintings so poignant. Such visual observa- tions are the language of his art, but few art historians these days would give them, as does Lightbown, the central attention they deserve.

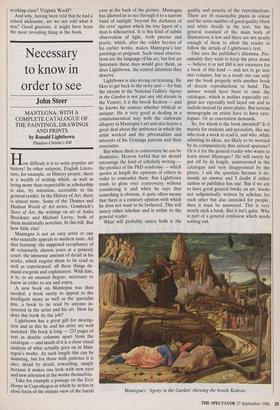

Lightbown is also strong on learning. He likes to get back to the story and — for him the stream in the National Gallery Agony in the Garden is not just any old stream in the Veneto, it is the brook Kedron — and he knows his sources whether biblical or antique. He is very good at dealing in a commonsensical way with the elaborate allegory in Mantegna's art and also learns a great deal about the ambience in which the artist worked and the personalities and interests of his Gonzaga patrons and their associates.

But where there is controversy he can be dismissive. Heaven forbid that we should encourage the kind of scholarly writing the product of the PhD syndrome — which quotes at length the opinions of others in order to contradict them. But Lightbown tends to gloss over controversy without considering it and when he says that something is obvious, it quite often means that there is a contrary opinion with which he does not want to be bothered.. This will annoy other scholars and is unfair to the general reader. What will probably annoy both is the quality and paucity of the reproductions. There are 16 reasonable plates in colour and the same number of good quality black and white details in the text, but the general standard of the main body of illustrations is low and there are not nearly enough of them to allow the reader to follow the details of Lightbown's text.

One sees the publisher's dilemma. Pre- sumably they want to keep the price down — believe it or not £60 is not excessive for a book of this kind — and not to go into two volumes, but as a result one can only use the book properly with another book of decent reproductions to hand. The answer would have been to omit the catalogue, which is neither especially ori- ginal nor especially well layed out and to include instead far more plates. But serious monographs on artists have to have cata- logues. Or so convention demands.

So, for whom is the book intended? Is it mainly for students and specialists, like me who took a week to read it, and who, while admiring its ideas, are likely to be worried by its comparatively thin critical aparatus? Or is it for the general reader who wants to learn about Mantegna? He will surely be put off by its length, uninterested in the catalogue and very disappointed by the plates. I ask the question because it de- mands an answer and I doubt if either author or publisher has one. But if we are to have good general books on art, books not solipsistically written by scholars for each other but also intended for people, then it must be answered. This is very nearly such a book. But it isn't quite. Why is part of a general confusion which needs sorting out.

Mantegna's 'Agony in the Garden' showing the brook Kedron.

Previous page

Previous page