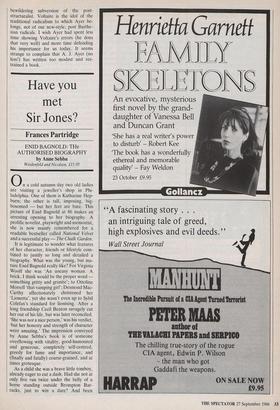

Have you met Sir Jones?

Frances Partridge

ENID BAGNOLD: The AUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY by Anne Sebba

Weidenfeld and Nicolson, £15.95

0 n a cold autumn day two old ladies are visiting a jeweller's shop in Phi- ladelphia. One of them is Katharine Hep- burn; the other is tall, imposing, big- bosomed — but her feet are bare. This picture of Enid Bagnold at 86 makes an arresting opening to her biography. A prolific novelist, playwright and memoirist, she is now mainly remembered for a readable bestseller called National Velvet and a successful play — The Chalk Garden.

It is legitimate to wonder what features of her character, friends or lifestyle com- bined to justify so long and detailed a biography. What was the young, but ma- ture Enid Bagnold really like? For Virginia Woolf she was 'An uneasy woman. A brick, I think would be the proper word something gritty and granite'; to Ottoline Morrell 'that vamping girl'; Desmond Mac- Carthy affectionately christened her tionetta', yet she wasn't even up to Sybil Colefax's standard for lionising. After a long friendship Cecil Beaton savagely cut her out of his life, but was later reconciled. `She was not a nice person,' was his verdict, tut her honesty and strength of character were amazing.' The impression conveyed by Anne Sebba's book is of someone overflowing with vitality, good-humoured and generous, completely self-centred, greedy for fame and importance, and (finally and fatally) coarse-grained, and at times grotesque.

As a child she was a brave little tomboy, already eager to cut a dash. Had she not at only five run twice under the belly of a horse standing outside Brompton Bar- racks, just to win a dare? And been whipped three times before she was 12? But by the time she arrived at Prior's Field, Mrs Huxley's prestigious girl's-school, she had become fat and unremarkable, and for a while her story takes on a tinge comically reminiscent of Arthur Marshall. 'Never by her own admission an intellectual' (and showing little interest in books then or later) 'she kept grass-snakes in her desk and hatched silkworms in her bedroom.' `Week after week she screamed inwardly: "Oh God, give me fame." ' But, a little later, 'Enid was losing some of her 11 stones.' By the time she left school 'she knew precisely what she wanted — an affair', with which in mind she decided to study drawing and moved into Bohemian circles, where she met Sickert, the 'inexperienced sculptor Gautier' and even 'the brilliant young artist Lovat Fraser. . . who looked every inch a dandy.' But in Frank Harris she met her fate. It was 'like being run over by the ocean. . . his very ugliness was attractive.' At 22 Enid was not lacking in feminine allure and Harris was partial to virgins.

The affair obsessed her and she gathered her love letters together into what she called her Death Journal, which nearly found a publisher years later when she was 89. 'All that ancient love for that ancient ruffian,' she wrote; 'it's like looking at one's face in a pond when one's dead.' At the time she knew she must `rebecome a virgin' and return to a conventional social life with marriage as its end. A year or two later she had fallen in love with Prince Antoine Bibesco, and before going to sleep at night she would pray to a God she barely believed in: 'Please make Antoine marry me.' But though this was probably her most passionate affair her happiness was short.

It was not until she was 31 that she made an unexpected match with Sir Roderick Jones, a precise, dapper little man, the son of a hat salesman and now proprietor of Reuters, who courted her formally with flowers, lace handkerchiefs and flattery. He was so absurdly small that when they danced his head disappeared in her ample bosom. Yet his pride in her loyalty to him kept the marriage alive in spite of a period of infidelities on both sides. Even more than the security and wealth he gave her, she valued his appreciation of her new success as a writer. The couple had four children, and in Roderick's old age Enid wrote to him: 'You have been the tree sheltering my whole life, the strongest man I ever knew and the tenderest.'

It would be difficult to say which Enid loved most — fame or the paraphernalia of wealth. She was honest about herself; she knew there were gaps in her intelligence as there were in her reading, but she worked very hard and took her few disappoint- ments (mostly on the stage) bravely. After all she had had outstanding success: National Velvet had been a best seller and ended up as a film. Serena Blandish and The Squire had both done well, though she had been disappointed by her failure to get a collected edition and Roderick's to be awarded a peerage. But her natural buoyancy was beginning to falter. Roderick died in 1962; her much-loved children had grown up and made their own lives. The measure of her loneliness was given in an advertise- ment in the Times for a self-contained person to assist 'savage old playwright. No tact required, taciturnity valued.'

At the age of 79 Enid Bagnold under- went a hip operation which left her in great pain, for which morphia was prescribed. She became and remained an addict until she died.

On the whole Anne Sebba gives a convincing portrait of someone who despite a touch of the clown in her make- up — disarmed by her vitality and good nature and so made many friends. I must protest that she has over-burdened it with a plethora of rather absurd detail. Do we really need to know that `the Joneses gravy had always been made with several pounds of shin of beef — with anything else the world seemed to be crumbling'? Or indeed that 'at Rottingdean some visitors liked the bath run for them, others preferred to run their own'? Yet she gives more space to such minutiae than to the loss of a leg by Enid's eldest son Timothy from a war wound. Must we be told about Enid's false teeth, over-eating, flatulence, false eye- lashes, wig, constipation and face-lift? Seb- ba has a gift for analysis, all too seldom used. She follows the American tradition whose motto is put everything in, I confess to being depressed by the result, and feeling nostalgia for a vanished style of biography — one based on selection, eco- nomy, concentration; one associated with French writers and with Lytton Strachey. Enid spent much of her life writing a patchy, spontaneous and often funny auto- biography. Perhaps that would have been enough.

Previous page

Previous page