I have not myself read either Fromm or

Burrow was convinced that at the root of our difficulties, as individuals and as a society, there lies an unjustifiable preoccupation in everybody with an image of himself—an 'l'-p& Bona—which overemphasises his separateness from others and his need to justify this separated self. The oppor- tunities given by means of language to symbolise our actions instead of just acting, and to preserve a discrepancy between what we are doing and what we persuade ourselves we are doing, seemed to him to have produced a flaw in the life of the whole species. The result has been 'all these . . . hundreds of thousands of years of our inad- vertent self-ostracism,' by which Burrow evi- dently meant to convey a more fundamental version of what Fromm has since then called the individual's alienation. Burrow's idea was that this self-ostracism involved a division between the individual's 'l'-persona and his own biological reality, which he possesses as a member of his species. it follows that this inner division is a very desperate form of separation from 'society': for Burrow insists that. the 'society' with which we have lost contact is not only the outer social world but the species of which we are biologi- cally part. It is something within each of us, our continuity with our species, from which we are separated.

This 'divisive' condition he regarded as the fundamental disorder in man. While others repeat the lamentation that our material resources have outstripped our moral capacity to use them properly, Burrow really tried to say what this 'moral' failure was. And he saw his work as doing something radical for our social condition (including our international condition). He writes to an old and sceptical friend :

You ask, 'How are we going to cure a disease which you apparently feel afflicts the whole of. humanity?' Freud once asked the same question, 'Does Burrow think he is going to cure the world?' But after all, why not?

And he compares his work with that of the early bacteriologists who, instead of treating individual patients, sought the common cause of their disease. He goes on, All that is needed, all that has ever been needed is that man know clearly, demonstrably what the matter is—what structure and what mechanism is disordered or impaired. Once the real focus of a disorder is clearly established, man pursues the remedy indefatigably.

to borrow rather freely from my thesis. Harry Stack Sullivan helped himself lavishly to my material. 1 knew him at Hopk'ns and he received

through the year all of my reprints.

It would have ,been easy for Burrow himself and his associates to communicate and popularise partial aspects of what he said, but to this he never. descended. He wanted his whole radical theory to be taken seriously by scientific workers.

It may secure new attention through the pub- lication of these letters. The book is primarily .t memorial of the man, but he was so fully and

Ordetrinell10211.111111.1211PrArall

`a triumph

for everyone concerned' SUNDAY TIMES

Undoubted

QUEEN

H. Tatlock Miller & Loudon Sainthill

the gift book of the year (639.)

ardently expressed in his work that his friends and family were all involved in it, and the letters to them as well as to his psychological colleagues present an outline of his theories as they de- veloped. His correction of the usual misunder- standings of his position, and the slight variations with which he expressed himself to different correspondents, all help to clarify views that his books sometimes leave obscure. The editing has been done tactfully and skilfully by a committee of his fellow-workers. Burrow appearS as a man of remarkable serenity in spite of the emotional strenuousness of the programMe he set himself with his close associates and the more ordinary invitations to anger, worry and discouragement that arose out of his breach with orthodox pro- fessional opinion. He is civilised and light in

Mr. Hoover

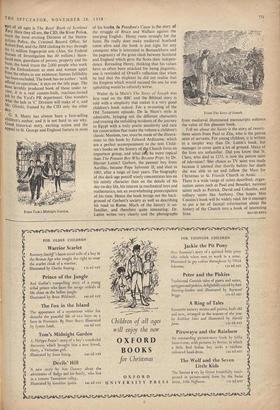

The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson. By AN eminent American has said that the most exclusive club in the world is that formed of ex-Presidents of the United States. And it might be thought, at first sight, that this latest book by Mr. Hoover is an addition to the literature of the club, a tribute from one former President to another. But it is much more than that. It is a moving tribute. Mr. Hoover has no doubt that Wilson was a great man and a great President, that some of the good he attempted to do was not interred with his bones, that the bad luck of his illness, combined with badjudgment (which the stroke accentuated), led to the great defeat —the refusal of the American people to join the League which their eloquent President had im- posed on his reluctant associates. The tragic story is told briefly in two juxtaposed photographs that show Wilson at the height of his powers and as the pathetic wreck who left the White House to the Ohio Gang in 1921. Thus, against his better judgment, Mr. Hoover supported the appeal for a Democratic Congress in 1918; he stayed on in Paris in response to a pathetic appeal from Wilson; he fought for the League cause in the Republican ranks (and, in vain, as President, for American adherence to the World Court). All this is no mere club politeness, but a deeply felt offering.

at Versailles

Previous page

Previous page