Something for everybody

J. G. Links

MODERN PAINTERS by John Ruskin edited and abridged by David Barrie

Deutsch, £17.95

Modem Painters is a huge and wonderful book — if five disparate volumes, published over a period of 17 years, can be called a book. It is impossible that an artist or art lover could read it without learning something of his subject, indeed that a human being could do so without learning something about himself. Any botanist or geologist would surely be absorbed by it, however critical he might be. Yet hardly anyone could be expected to read the 2,500 pages it takes up in the Library Edition, even if he could lay his hands on a copy for long enough to read it. Ruskin was conscious of this and much later wanted to break it up into 'four separate books, cutting out nearly all the preaching, and a good deal of the senti- ment'; this was just one of his innumerable 'wants' of the time which came to nothing. Then his friend, Charles Eliot Norton, wanted to take on the task with Ruskin's encouragement, concentrating on the 'art, imagination and morality', leaving out the science and the sentiment. This foundered when Ruskin found the passage he thought 'worth all the rest of the book, — marked — "Omit to end of Chapter" ', and real- ised he had trusted the wrong man. I myself felt ready to try Modern Painters after I had abridged The Stones of Venice. I was minded to leave out all references to God but my publishers demurred, rightly I now feel sure, so the book was never published and I was saved a good haunting from Ruskin's ghost. Many others must have had the same wish to make the delights of Ruskin accessible without the pains.

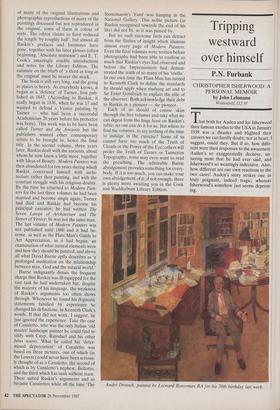

David Barrie has succeeded where so many have been daunted and will certainly have the profound gratitude of his readers. Here is a one-volume edition of 656 pages including an index (Ruskin left this to his schoolgirls and the Library Edition does not provide a separate one), and an in- formative and intelligent introduction and notes. There are acceptable reproductions of many of the original illustrations and photographic reproductions of many of the paintings discussed but not reproduced in the original, some of them in colour of sorts. The editor claims to have reduced the length 'by roughly half, but almost all Ruskin's prefaces and footnotes have gone, together with his later glosses (often beginning, 'Absolute nonsense') and E. T. Cook's amazingly erudite introductions and notes for the Library Edition. The estimate on the blurb of 'a third as long as the original' must be nearer the mark.

The book is still very long, and the going in places is heavy. As everybody knows, it began as a 'defence' of Turner, first pub- lished in 1843. (According to Ruskin, it really began in 1836, when he was 17 and wanted to defend a Venice painting by Turner — who had been a successful Academician 20 years before his protector was born). This work was to be have been called Turner and the Ancients but the publishers wanted other contemporary artists to be brought in, hence the final title. In the second volume, three years later, Ruskin dealt with the ancients, about whom he now knew a little more, together with Ideas of Beauty. Modern Painters was then abandoned for ten years during which Ruskin concerned himself with archi- tecture rather than painting, and with the constant struggle with his religious doubts. By the time he returned to Modern Pain- ters for the last three volumes he had been married and become single again; Turner had died and Ruskin had become his principal executor; he had written The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice; he was not the same man. The last volume of Modern Painters was not published until 1860 and it had be- come, as well as the Plain Man's Guide to Art Appreciation, as it had begun, an examination of what natural elements were and how they should be painted, and above all what David Barrie aptly describes as 'a prolonged meditation on the relationship between man, God and the natural world.'

Barrie indignantly denies the frequent charge that Ruskin was ill-equipped for the vast task he had undertaken but, despite the majesty of his language, the weakness of Ruskin's arguments too often shows through. Whenever he found his dogmatic statements falsified by experience he changed his definitions, in Kenneth Clark's words. If that did not work, I suggest, he just ignored the experience. Take the case of Canaletto, who was the only Italian 'old master' landscape painter he could find to vilify with Cuyp, Ruysdael and his other bêtes noires. What he called his 'deter- mined depreciation' of Canaletto was based on three pictures, one of which (in the Louvre) could never have been serious- ly thought of as a Canaletto, the second of which is by Canaletto's nephew, Bellotto, and the third which has sunk without trace. These suited Ruskin's arguments and so became Canalettos while all the time 'The Stonemason's Yard' was hanging in the National Gallery. This noble picture (as Ruskin recognised towards the end of his life) did not fit, so it was passed by.

But no such tiresome facts can detract from the flashes of insight which illumine almost every page of Modern Painters. Even the final volumes were written before photography had been able to confirm so much that Ruskin's eyes had observed and before the Impressionists had demon- strated the truth of so many of his 'truths'. In our own time the Plain Man has turned to Kenneth Clark to define the standards he should apply when studying art and to Sir Ernst Gombrich to explain the role of the observer. Both acknowledge their debt to Ruskin as a pioneer — the pioneer.

Each of us should of course skim through the five volumes and take what we can digest from the huge feast on Ruskin's table; no one can do it for us. But where to find the volumes, to say nothing of the time to indulge in the exercise? Some of us cannot have too much of the Truth of Clouds or the Power of the Eye; others will prefer the Truth of Turner or Tumerian Topography; some may even want to read the preaching. The admirable Barrie abridgement provides something for every- body. If it is too much, you can make your own abridgement of it; if not enough, there is plenty more awaiting you in the Cook and Wedderburn Library Edition.

Previous page

Previous page