Talking of books

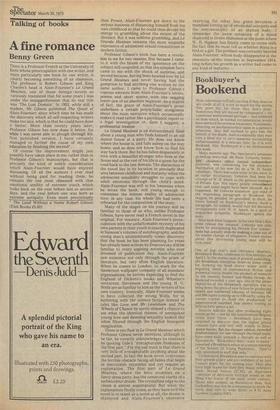

A fine romance

Benny Green

There is a Professor French at the University of Kent whose preoccupation with one writer, and more particularly one book by one writer, is clearly becoming something of an obsession. The professor is Robert Gibson and King Charles's head is Alain-Fournier's Le Grand Mealnes, one of those foreign novels so variously translated that for some years I was under the misapprehension that its real title was 'The Lost Domain.' In 1953, while still a student, Mr Gibson published The Quest of Alain-Fournier, since which time he has made the discovery which all self-respecting writers make too late, which is that he could have done it better. More than twenty years later, Professor Gibson has now done it better, for while I was never able to plough through his first published version, I have certainly managed to further the cause of my own education by finishing the second*. Of course the improvement might just possibly have taken place in me, rather than in Professor Gibson's manuscripts, but that is precisely the kind of subtle consideration which Alain-Fournier would have enjoyed discussing. Of all the authors I ever read without being paid for reading them, he remains the one most obsessed with that emotional senility of extreme youth which looks back on the year before last as ancient days, and the year before one was born as extreme antiquity. Even more precociously * The Land Without a Name Roberf Gibson (Elek Books £5.80) than Proust, Alain-Fournier got down to the serious business of distancing himself from his own childhood so that he could then devote his energy to grumbling about the extent of the distance. But it was sublime grumbling, and Le Grande Mealnes remains the most exquisite expression of adolescent sexual romanticism in modern fiction.

Professor Gibson's book has been a revelation to me for two reasons; first because I came to it with the bloom of my ignorance on the subject still unspoiled, so that the simplest facts came to me with the shock of surprise, and second because, having been bowled over by Le Grand Mealnes and never having had the gumption to find anything else written by the same author, I came to Professor Gibson's copious extracts from Alain-Fournier's letters, poems and short stories, with the sagging lower-jaw of an absolute beginner. As a matter of fact, the grace of Alain-Fournier's prose underlines a certain polysyllabic stodginess about the main narrative which occasionally makes it read rather like a psychiatric report or a legal investigation or, dare I suggest, a professorial treatise.

Le Grand Mealnes is an extraordinary fable about a young man who finds himself in an old manor house at a party. He does not know where the house is, and falls asleep on the way home, and so does not know how to find his way back there. But he has fallen desperately in love with a beautiful stranger who lives at the house and so the rest of his life is a quest for the road back to the lost domain. The distinction of the novel lies in its location in precisely that area between childhood and maturity when the adolescent sensibility struggles to cope with adult emotions through the child's mind. Alain-Fournier was still in his 'twenties when he wrote the book, still young enough to remember the intense reality of adolescent love; in any case, his whole life had been a rehearsal for the composition of the story.

Many of the stages on his journey will be familiar to those of us who, unlike Professor Gibson, have never read a French novel in the original. For instance, Alain-Fournier's preoccupation with the unfathomable mystery of his own parents in their youth is exactly duplicated in Sassoon's volumes of autobiography, and the young man's unintentionally comic discovery that the book he has been planning for years has already been written by Dostoievsky will be familiar to every aspiring novelist who ever dreamed of publication day. Alain-Fournier saw existence not only through the prism of literature, but very often English literature. When he comes to London, to work for the Sanderson wallpaper company of all mundane organisations, he arrives expecting to find the England of Dickens's books and Whistler's nocturnes; Stevenson and the young H. G.

Wells are as familiar to him as the writers of his own country. Ironically, Alain-Fournier seems to have collected the wrong Wells, for in bothering with the science fiction instead of tales like Love and Mr Lewisham and The Wheels of Chance he surely missed a chance to see what the identical themes of unrequited young love and dawning sexuality looked like when filtered through the English bourgeois imagination. There is one flaw in Le Grand Mealnes which Professor Gibson never mentions, although to be fair, he covertly acknowledges its existence by quoting Gide's "irrecapturable freshness of the first part."_For the sad truth is that there is very little of irrecapturable anything about the second part. In fact the book never overcomes the terrible obstacle facing all fables that begin as inscrutable mysteries and yet require an explanation. The first part of Le Grand Mealnes, where the hero stumbles on a fancy-dress party, has the unnatural clarity of a technicolour dream. The crystalline edge to the vision is almost supernatural. But when the explanations finally come, as they have to if the novel is to stand as a novel at all, the dream is shattered and Alain-Fournier's obsessive yearning for what has gone becomes a mundane totting up of emotional accounts and the sentimentality of an orphan baby. I remember the same sensation of a mood shattered in Green Mansions at the point where W. H. Hudson has finally come to terms with the fact that he must tell us whether Rima is a bird or a girl. The problem was certainly beyond Alain-Fournier, whose body disappeared in the obscenity of-the trenches in September 1914, long before his growth as a writer had come to any kind of maturity.

Previous page

Previous page