Photography

Branded Youth and Other Stories (National Portrait Gallery, till 8 February)

Over exposure

Simon Blow

Bruce Weber is a photographer wor- shipped by wannabes. He is an icon to thousands, possibly millions. In these times of street culture, Weber is a god. If he holds his lens at a new angle, street culture knows of it. It doesn't matter if the new angle has much to reveal or not, Mr Weber is an icon. True, he has made a number of photographic 'image' inroads — with homo-eroticism (now dated) and fashion shoots — but does this warrant him an enviable creative genius status? No, because it's a reputation hyped by a down- market media who are largely responsible for this sadly ignorant condition which has been swankily labelled 'street culture'. They have encouraged a naive public to become media-obsessed dolts, swallowing whatever is sent their way. I say this because the market-place sends out only the most easily accessed of comments. Any stimulating, probing adventure it would not entertain. And so Bruce Weber is sent forth as a messianic Tolstoy of the modern market-place.

Forgive the analogy, for the market- place would give Tolstoy zero rating. His words would be daubed only on the walls of the National Portrait Gallery if they had first been blessed by Bruce Weber. So Scott Fitzgerald shines forth to millions who have never read — or heard of — This Side of Paradise because Weber has plucked a Fitzgerald aphorism to enhance his non-verbal images. 'I don't want to `Leonardo DiCaprio, Coney Island, 1994 repeat my innocence. I want the pleasure of losing it again,' scrawls Weber via Scott Fitzgerald on a wall. And on another wall of this exhibition he has a message of his own for all of us: 'A lot of people think `Tina Turner in Rocking Chair, 1990 having a big fantasy life is dangerous, maybe that's why someone's always trying to take it away from you.' Profound think- ing, Mr Weber.

But then his words, the market-place has decreed, are to enter the imaginations of millions, not just the few. This is iconspeak. There is nothing dangerous in anything Weber has to say, just as there is nothing dangerous in his photographs. If pho- tographs can state, then what they contain — here and there — are some ironic com- ments. This is good, since irony is a condi- tion rarely understood by Weber and his fellow countrymen. And Weber is an American living on a dude ranch in Cali- fornia. But he also has a studio in New York and his journeys have long been international. Good things can happen to Americans when they travel.

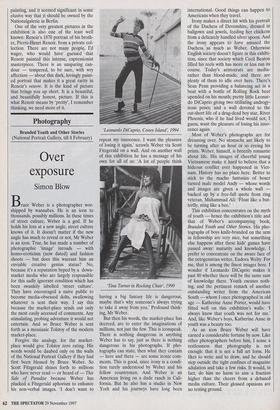

Irony makes a direct hit with his portrait of the Duchess of Devonshire, dressed in ballgown and jewels, feeding her chickens from a delicately handled silver spoon. And the irony appears to have amused the Duchess as much as Weber. Otherwise English society doesn't figure in this exhibi- tion, since that society which Cecil Beaton filled his reels with has more or less run its course. Today's aristocrats are media- rather than blood-made, and there are plenty of them to idle over here. There's Sean Penn providing a balancing act in a boat with a bottle of Rolling Rock beer upended on his mouth; pretty little Leonar- do DiCaprio giving two titillating androgy- nous poses; and a wall devoted to the cut-short life of a drug-dead boy star, River Phoenix, who if he had lived would not, I guess, want the pleasure of losing his inno- cence again.

Most of Weber's photographs are for dreaming over. No stomachs are likely to be turning after an hour or so eyeing his prints. Weber, himself, is breezily romantic about life. His images of cheerful young Vietnamese make it hard to believe that a hideous conflict ever happened in Viet- nam. History has no place here. Better to stick to the macho fantasies of boxer turned male model Andy — whose words and images are given a whole wall backed up by a free-fall quote from ring veteran, Muhammad Ali: 'Float like a but- terfly, sting like a bee.'

This exhibition concentrates on the myth of youth — hence the exhibition's title and that of Weber's accompanying book, Branded Youth and Other Stories. His pho- tographs of boys knife-branded on the arm in fellowship are very nice, but something else happens after these kids' games have passed away: maturity and knowledge. I prefer to concentrate on the aware face of the octogenarian writer, Eudora Welty. For me, that is among the finest images here. I wonder if Leonardo DiCaprio makes it past 80 whether there will be the same sum of knowledge there. Youth excuses noth- ing, and the pertinent remark of another outstanding writer from the American South — whom I once photographed in old age — Katherine Anne Porter, would have fitted well on this exhibition's walls: 'I always knew that youth was not for me.' And, like Weber's boys, Katherine Anne in youth was a beauty too.

As an icon Bruce Weber will have earned a considerable fortune by now. Like other photographers before him, I sense a restlessness that photography is not enough: that it is not a full art form. He likes to write and to draw, and he should step outside the tight confines of magazine adulation and take a few risks. It would, in fact, do him no harm to aim a fraction higher than the cheers from a debased media culture. Their glossed opinions are no testing ground.

Previous page

Previous page