ARTS

Cinema 1

A certain audacity

ortunately I am not an actor who ever got into the habit of refusing film roles, holding that if one doesn't read the script in advance, or ever see the finished product, there is nothing to prevent one accepting the money and then spending it.'

In a studio career of some 53 years, my father made just over 80 films, from Marie Antoinette in 1938 to The Lady and the Highwayman (don't ask) in 1991, and his absolute refusal to take all of them serious- ly, or to accept the automatic authority of the writer and director over that of the actor, was a perpetual source of annoyance to his more humourless and portentous critics. But in truth he made some quite remarkable and wonderful films along the way, and it is in an attempt to prove this that I have put together the season of a dozen of them which starts at the National Film Theatre in London this Saturday. My father's attitude to film directors much resembled the way he treated stage direc- tors: 'I give them 20 minutes, to discover if they know any more than I do, and if they don't then I just get on and do it myself'.

Yet he worked with many of the best: John Huston employed him three times (twice with Humphrey Bogart, on The African Queen and then Beat the Devil). Elsewhere he was lucky enough to star for Gabriel Pascal, Carol Reed, Anthony Asquith, Jules Dassin, Peter Glenville and, rather less happily, Tony Richardson. Of course he was a 'personality actor', if by that we mean that many directors and not a few screenwriters, in trouble with a character or a scene, would send for Robert the way they would send for Peter Ustinov or David Tomlinson or Wilfred Hyde White, knowing they would fill out an underwritten moment and bring something of their own (often a lot) to bear on an oth- erwise threadbare character or situation. But Robert only relied on his larger-than- life personality when there was no help forthcoming from any other source.

'If I have learnt anything in a long life,' he once wrote, 'it is that there is really not a very great deal to acting, beyond a certain audacity. I do it mainly for the lolly, and am no longer capable of learning new tricks, so directors are now stuck with a resolute, elderly comedian. I see it as my

'F

job to entertain as best I can: it's much like being a waiter, without having to worry about the food or the tips. Just save the audience from as much agony as possible for the short time they are with you. That's what it's all about, I think.'

But that was written towards the end of his life, when the British film industry had collapsed around him and he was seldom getting scripts of any real value. It was not ever thus: he started out before the war in Hollywood, got an Oscar nomination for his very first film (Marie Antoinette, in which he played Louis XVI to the Louis XV of John Barrymore, and won) and could have stayed there forever.

He was indeed offered The Hunchback of Notre Dame, but turned it down on the grounds that it appeared to be a grunting rather than speaking role: it went, famous- ly, to Charles Laughton and I once asked Robert if he had ever regretted the lost opportunity: 'Not at all: Laughton was at RADA just before me, and put a lot of courage and hope into us fatties, but I should have hated to end up like him, for- ever waiting around a Hollywood pool to be insulted. Mind you, Hollywood before the war was a wonderful place to be: on Marie Antoinette, Norma Shearer insisted we have a live studio orchestra to while away the waiting time between shots. She had it in her contract, because she believed she always acted better to orchestral accompaniment. Then there was the maitre d'hotel who came around to take our orders for luncheon, which would be deliv- ered to our dressing-rooms by liveried wait- ers. Those were the days.'

Except perhaps for Louis B. Mayer, who had to pay for it all: 'Jesus, but I hate histo- ry,' were his first words to Robert on learn- ing that here was yet another actor out from England to make yet another expen- sive costume epic on his back lot. 'We got them all here, though,' he added, warming up a little, 'every star in the heavens. Except of course for that damn Mouse over at Disney.'

Declining to stay even long enough to see if he had won the Oscar, Robert returned to Broadway and the West End and the 'real' world of theatre which was always to be his first home. Soon after- wards, he worked with Wendy Hiller and Sybil Thorndike and Rex Harrison on the film of Major Barbara, and met on the set the only saint he ever acknowledged, Bernard Shaw, the man who had made him into an actor when one afternoon on the pier at Folkestone in 1924 an ungainly, unhappy, lonely teenager had walked into a theatre, seen Esme Percy in The Doctor's Dilemma and known at once and forever that he too was going on to the stage.

During Major Barbara came the war, and Robert did not make another good film for a decade: but then, at the beginning of the 1950s, came Outcast of the Islands and The African Queen, the latter somewhat terrify- ing in that he was the only other actor in a picture otherwise possessed by Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart. On the first day of shooting he was, uncharacteris- tically, overcome by nerves and returned to his theatre that night (he made the vast majority of his films while playing eight shows a week on Shaftesbury Avenue) more than a little depressed. After the show there happened to be a party, at which Robert found to his horror both Huston and Hepburn. 'What's it like', asked a journalist, 'having Morley now on the film with you?' Mr Morley', said Hep- burn, 'starts working with us tomorrow', and he did, giving one of his best if briefest performances as the dying missionary.

In later life he became a genial villain (Topkapi, Hot Millions) or the victim of elaborate murder plots (Theatre of Blood, Someone is Killing the Great Chefs of Europe) but he was also much in demand for foreign royalty. In Genghis lawn he was an unlikely Emperor of China, not least because he insisted in sticking his pigtail to the back of his hat in order to save time in the make-up chair each morning. He was also Louis XIII, George III, Charles James Fox, W.S. Gilbert and Oscar Hammerstein I. He could even be found dancing with Cliff Richard, talking to the Muppets and supporting Benji the Wonder Dog, not to mention Bing Crosby and Bob Hope at the very end of their Road pictures.

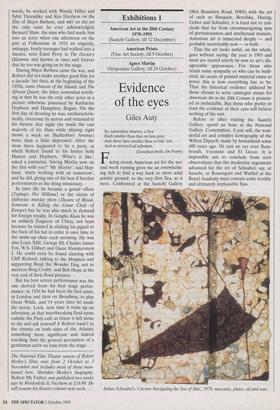

But his best screen performance was the one derived from his best stage perfor- mance: in 1936 he had been the first actor, in London and then on Broadway, to play Oscar Wilde, and 14 years later he made the movie. Look, next time it turns up on television, at that heartbreaking final scene outside the Paris café as Oscar is left alone to die and ask yourself if Robert wasn't to the cinema on both sides of the Atlantic something more significant and indeed touching than the general perception of a gentleman actor on loan from the stage.

Previous page

Previous page