Exhibitions 1

American Art in the 20th Century 1970-1993 (Saatchi Gallery, till 12 December) American Prints (Fine Art Society, till 9 October) Agnes Martin (Serpentine Gallery, till 24 October)

Evidence of the eyes

Giles Auty

So, naturalists observe, a flea Hath smaller fleas that on him prey; And these have smaller fleas to bite 'em,

And so proceed ad infinitum.

(Jonathan Swift, On Poetry) Facing recent American art for the sec-

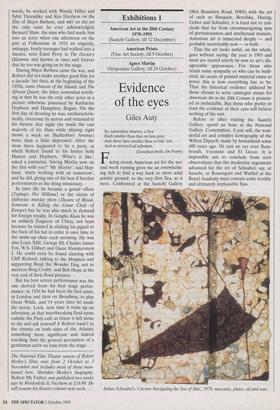

ond week running gives me an overwhelm- ing itch to find a way back to more solid artistic ground: to the very first flea, as it were. Confronted at the Saatchi Gallery (98A Boundary Road, NW8) with the art of such as Basquiat, Borofslcy, Haring, Gober and Schnabel, it is hard not to con- clude that far from circumnavigating seas of portentousness and intellectual manure, American art is immersed deeply — and probably inextricably now — in both.

That the art looks awful, on the whole, goes without saying: the year is 1993 and most are inured utterly by now to art's dis- agreeable appearance. For those who retain some sympathy or who can be both- ered, an ocean of printed material exists to prove this is how everything has to be. Thus the historical evidence adduced by those chosen to write catalogue essays for American Art in the 20th Century is present- ed as ineluctable. But those who prefer to trust the evidence of their eyes will believe nothing of the sort.

Before or after visiting the Saatchi Gallery, spend an hour at the National Gallery. Contemplate, if you will, the won- derful art and complex iconography of the Wilton Diptych, made by humankind some 600 years ago. Or cast an eye over Rem- brandt, Veronese and El Greco. It is impossible not to conclude from such observations that the modernist arguments advanced for the art of Schnabel, say, at Saatchi, or Rosenquist and Warhol at the Royal Academy must contain some terrible and ultimately implausible flaw.

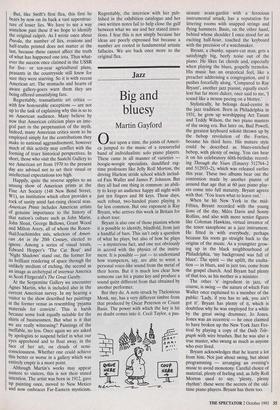

Julian Schnabel's `Circum-Navigating the Sea of Shit', 1979, masonite, plates, oil and wax

But, like Swift's first flea, this first lie bears by now on its back a vast superstruc- ture of lesser lies. We have to see a way somehow past these if we hope to identify the original culprit. As I wrote once about Pravda, the number of lies, evasions and half-truths printed does not matter at the last, because these cannot affect the truth of what has happened one iota. Thus what- ever the success once claimed in the USSR for five- or ten-year agricultural plans, peasants in the countryside still knew for sure they were starving. So it is with recent American art. The stomachs and hearts of aware gallery-goers warn them they are being offered unsatisfying fare.

Regrettably, transatlantic art critics — with few honourable exceptions — are not up to the task of explaining why this is so to an American audience. Many believe by now that American criticism plays an inte- gral part in the perpetuation of the myth. Indeed, many American critics seem to be employed simply for the contributions they make to national aggrandisement, however much of this activity may conflict with the forming of truer historical perspectives. In short, those who visit the Saatchi Gallery to see American art from 1970 to the present day are advised not to set their visual or intellectual expectations too high.

Happily, quite the reverse applies to an unsung show of American prints at the Fine Art Society (148 New Bond Street, W1), an institution which often provides a rock of sanity amid fast-rising cloacal seas. American Prints includes American artists of genuine importance to the history of that nation's culture such as John Mann, John Sloan, George Bellows, Grant Wood and Milton Avery, all of whom the Rosen- thal/Joachimides axis, selectors of Ameri- can Art in the 20th Century, elected to ignore. Among a series of visual treats, Edward Hopper's 'The Cat Boat' and 'Night Shadows' stand out, the former for its brilliant rendering of space through the unlikely medium of etching, the second as an image as archetypal of interwar America as Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby.

At the Serpentine Gallery we encounter Agnes Martin, who is included also in the current American survey. In my hearing a visitor to the show described her paintings at the former venue as resembling 'pyjama materials for convicts'. This is harsh because some look equally suitable for the Shirts of businessmen. But what is it that we are really witnessing? Paintings of the ineffable, no less. Once again we are asked by apologists to suspend belief in what our eyes apprehend and to float away, in the face of her art, on clouds of semi- consciousness. Whether one could achieve this better or worse in a gallery which was entirely empty is a moot point.

Although Martin's works may appear austere to visitors, this is not their stated intention. The artist was born in 1912, gave Up painting once, moved to New Mexico and now embraces Far-Eastern mysticism.

Regrettably, the interview with her pub- lished in the exhibition catalogue and her own written notes fail to help close the gulf between what we see and her stated inten- tions. I fear this is not simply because her ideas are poorly expressed but because a number are rooted in fundamental artistic fallacies. We are back once more to the original flea.

Previous page

Previous page