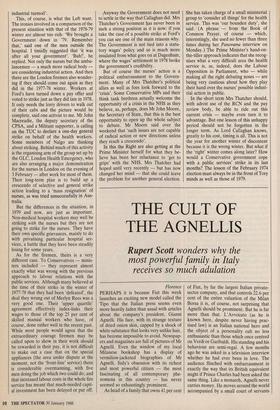

THE CULT OF THE AGNELLIS

Rupert Scott wonders why the

most powerful family in Italy receives so much adulation

Florence PERHAPS it is because Fiat this week launches an exciting new model called the Tipo that the Italian press seems even more heavily laden than usual with articles about the company's president, Gianni Agnelli. His face, with its strange texture of dried onion skin, capped by a shock of white substance that looks very unlike hair, has become impossible to avoid. Newspap- ers and magazines are full of pictures of Mr Agnelli. Even the window of my local Milanese bookshop has a display of vermilion-jacketed biographies of Mr Agnelli. Italy's obsession with its richest and most powerful citizen — the most fascinating of all contemporary phe- nomena in this country — has never seemed so exhaustingly prominent.

As head of a family that owns 41 per cent of Fiat, by far the largest Italian private- sector company, and that controls 22.6 per cent of the entire valuation of the Milan Borsa it is, of course, not surprising that Agnelli should be prominent. But he is far more than that. L'Avvocato (as he is known here, despite never having prac- tised law) is an Italian national hero and the object of a personality cult no less enthusiastic than those which once centred on Verdi or Garibaldi. His standing and his behaviour are semi-regal. A few months ago he was asked in a television interview whether he had ever been in love. The audience flinched with embarrassment in exactly the way that its British equivalent might if Prince Charles had been asked the same thing. Like a monarch, Agnelli never carries money. He moves around the world accompanied by a small court of servants and advisors. In Italy he is permanently accompanied by police and bodyguards.

Putting Gianni Agnelli's face on the cover of a magazine boosts its sale by between five and ten per cent. This is because reading about l'Avvocato is some- thing for which his compatriots have ex- traordinary enthusiasm (not to mention stamina). Their preferred reading has a faintly embarrassing resemblance to the sort of propaganda about Mussolini that once appeared in II Popolo &Italia. A recent example in the weekly Panorama was a classic of the genre. From it I learnt what sort of tea l'Avvocato drinks for breakfast, that he rises without fail at 6.30, and that he smokes only one cigarette after dinner. His capacity for work, I read, is as great as his capacity for play. He loves sport and speed, and as if to prove the point there were lots of flattering pictures of Agnelli in sporting poses — stripped to the waist at the helm of Azzurro III (his boat), whizzing down the slopes of Ses- triere (his ski resort) and watching Juven- tus (his football team) play at home on a Sunday afternoon. This sort of article, I should add, is not at all unusual. Similar things regularly appear in most sections of the press.

Since Italians have an instinctive respect for rather than (as in Britain) distrust of wealth, the depth of such credulous hero- worship in a country in many ways so sophisticated is less strange than it might first appear. In a relatively young country still divided by region, where politicians are despised and civil servants mistrusted, he and Fiat (which is highly successful) provide a focus for national pride. For the great majority of Italians the interests of Agnelli, and thus of Fiat, are identified with the interests of Italy itself. Indeed the mere suggestion that they are not can provoke, amongst Italians of all classes and ages, a very hostile reaction indeed. Whether, in fact, this is the case is something far from obvious to those who take a more cynical view of Agnelli and of Fiat. The degree of power now concen- trated in the hands of one family, and in effect just one member of that family, must be disturbing even to those who do not subscribe to theories of capitalist conspira- cy. Fiat estimates its turnover for 1987 at £17 billion, just over half of which will be derived from car manufacture. But Fiat is far more powerful than companies of similar size like Siemens in Germany or Nestle in Switzerland. This is because the Italian economy, made up of much small industry and a few sluggish state corpora- tions, offers it no serious competition. Fiat's political power is also immense, since its horizontal spread of businesses (only just over half of turnover derives from making cars) brings most members of government and parliament within its lob- bying range. As Claudio Martelli, Craxi's deputy in the Socialist Party, said last week, Fiat has begun to look very like 'a state within a state', answerable to no one but itself, or more accurately, no one but Agnelli.

Nothing demonstrates the power of Fiat and the Agnellis better than the events of the last 18 months, which have witnessed a series of controversial acquisitions and potential scandals. In September 1986 Fiat achieved a monopoly over Italian car production when it bought state-owned Alfa Romeo. The effective price of the acquisition (which brought Fiat six per cent of the home market and considerable foreign sales) was, according to the Euro- pean Commission in Brussels which is still investigating the deal, only £200 million.

Afew weeks later came the highly controversial public flotation of a 15.6 per cent stake held in Fiat by Colonel Gadda- fi's Lafico, the Libyan Arab Financial Investment Company. This was a complex and ingenious deal, the details of which well illustrate the less than altruistic princi- ples of Fiat's owners. Lafico wanted a high price for its holding, roughly half of which was in voting ordinary shares. Most of these the Agnellis wanted for themselves. The flotation was arranged by Medioban- ca, a close Fiat ally. In late September 1986 there was heavy buying of Fiat shares from 'unknown sources' and the share price shot to L16,600. This valued Lafico's holding at over $3 billion, which must have made a sale irresistible to Colonel Gaddafi. Then in came Mediobanca which lent Agnelli $1.1 billion in the form of a convertible bond bought by Fiat with an average interest rate of 2.6 per cent. This matured after 11 years into stock in three companies until then controlled by IFL and IFIL, the Agnelli family financial vehicles, and therefore already a part of Fiat. In other words Agnelli effectively borrowed at a ludicrously low rate of interest from Fiat shareholders in order to purchase 10 per cent of the voting stock in Fiat itself.

The flotation of the remaining stock, underwritten principally by Deutsche Bank, was a disaster from which the Milan Borsa has never quite recovered. The mystery buyers of Fiat stock suddenly disappeared and its price began to plum- met (it now stands at around L 8,500).

Deutsche Bank was left with enormous amounts of overvalued shares on its books (one billion deutschmarks' worth last September). For Agnelli, who secured 10 per cent of the voting shares, and Gaddafi, who made a handsome profit on an original investment (of about $250 million, made in 1976), the deal was a success. But for everyone else it was a disaster.

In August 1987 the French magazine L'Evenement du Jeudi claimed that a joint venture company owned 50 per cent by Fiat had been exporting large numbers of the other 50 per cent) of the company Ferdinando Borletti, a main board mem- ber of Fiat and president (as well as owner of the other 50 per cent) of the company, was subsequently arrested for 10 days and questioned by magistrates in Massa investi- gating illegal arms trafficking. Then last November Fiat called off, in the face of all commercial logic, a long-planned merger of its telecommunications subsidiary with the overlapping state firm Italtel, thus thwarting government plans to rationalise a strategically important industry.

How has Fiat managed to survive all this with hardly a dent in its shining corporate image? Firstly, of course, because of the cult of the Agnellis, and secondly, perhaps more sinisterly, through Agnelli's personal influence on the Italian press. Fiat has 24.8 per cent of daily newspaper sales. It owns La Stampa in Turin, and controls 11 Cor- riere della Sera in Milan. Besides these Agnelli has unquestioned influence on at least two other important and influential papers — La Repubblica, which is owned by his brother-in-law, Carlo Caracciolo, (though it is edited by the highly respected Eugenio Scalfari), and Ii Sole 24 Ore. This is a business paper published by the Con- findustria, the Italian CBI, of which Agnel- li is the leading member. Other newspap- ers are wary of criticising Fiat, since its advertising budget of £280 million, 13 per cent of the national total, is by far the largest in Italy. As a result, articles damag- ing to the interests or to the image of Fiat or the Agnellis very rarely see the light. The cult, therefore, is carefully nurtured.

Recent weeks have provided two exam- ples of Fiat's reaction to adverse publicity. In mid-January the company threatened to sue Which magazine for calling the Uno a 'lemon'. In December it lodged a formal complaint of criminal defamation with the Turin prosecutor's office against the Finan- cial Times and its Milan correspondent, Alan Friedman. It may be no coincidence that Friedman is writing a book about contemporary Italy that will deal at length with the affairs of Fiat and the Agnellis in recent years.

Gianni Agnelli is now 66. That his rather haggard looks belie a still dynamic spirit was made clear only last week when he appeared before a Senate committee in Rome investigating the need for anti- monopoly legislation in Italy. In a brilliant performance he dismissed accusations that Fiat was too powerful as 'utterly absurd'.

The press, needless to say, agreed with him wholeheartedly. What looked like the most serious political threat to the Agnelli dynasty for decades was effectively turned into a critique of the inefficiencies of state industry. It served as a reminder that for as long as it is protected by l'Avvocato Fiat is in no serious danger.

And when it is not? Only one thing is certain, that the Agnelli dynasty will con- tinue to control one of the foremost industrial conglomerates in Europe for many years to come. Whether they will continue to be so dearly loved, however, is open to question.

Previous page

Previous page