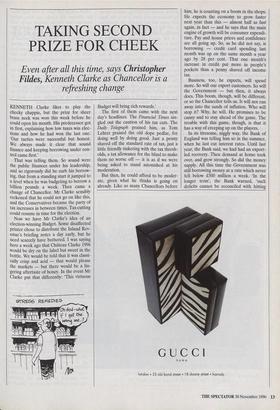

TAKING SECOND PRIZE FOR CHEEK

Even after all this time, says Christopher Fildes, Kenneth Clarke as Chancellor is a

refreshing change

KENNETH Clarke likes to play the cheeky chappie, but the prize for sheer brass neck was won this week before he could open his mouth. His predecessor got in first, explaining how low taxes win elec- tions and how he had won the last one: 'Our tactics were successful but honest. We always made it clear that sound finance and keeping borrowing under con- trol came first.'

That was telling them. So sound were the public finances under his leadership, and so rigorously did he curb his borrow- ing, that from a standing start it jumped to a level when he was budgeting to borrow a billion pounds a week. Then came a change of Chancellor. Mr Clarke sensibly reckoned that he could not go on like this, and the Conservatives became the party of tax increases in between times. Tax-cutting could resume in time for the election.

Now we have Mr Clarke's idea of an election-winning Budget. Some disaffected printer chose to distribute the Inland Rev- enue's briefing notes a day early, but he need scarcely have bothered. I was saying here a week ago that Château Clarke 1996 would be dry on the label but sweet in the bottle. We would be told that it was classi- cally crisp and acid — that would please the markets — but there would be a lin- gering aftertaste of honey. In the event Mr Clarke put that differently: 'This virtuous Budget will bring rich rewards.'

The first of them came with the next day's headlines. The Financial Times sin- gled out the caution of his tax cuts. The Daily Telegraph praised him, as Tom Lehrer praised the old dope pedlar, for doing well by doing good. Just a penny shaved off the standard rate of tax, just a little friendly tinkering with the tax thresh- olds, a tax allowance for the blind to make them no worse off — it is as if we were being asked to stand astonished at his moderation.

But then, he could afford to be moder- ate, given what he thinks is going on already. Like so many Chancellors before him, he is counting on a boom in the shops. He expects the economy to grow faster next year than this — almost half as fast again, in fact — and he says that the main engine of growth will be consumer expendi- ture. Pay and house prices and confidence are all going up. So, as he did not say, is borrowing — credit card spending last month was up on the same month a year ago by 28 per cent. That one month's increase in credit put more in people's pockets than a penny shaved off income tax.

Business, too, he expects, will spend more. So will our export customers. So will the Government — but then, it always does. This boom, though, will be different, or so the Chancellor tells us. It will not run away into the sands of inflation. Who will stop it? Why, he will. He promises to be canny and to stay ahead of the game. The trouble with this game, though, is that it has a way of creeping up on the players.

In its tiresome, niggly way, the Bank of England was telling him so in the summer, when he last cut interest rates. Until last year, the Bank said, we had had an export- led recovery. Then demand at home took over, and grew strongly. So did the money supply. All this time the Government was still borrowing money at a rate which never fell below £500 million a week. 'In the longer term', the Bank warned, 'such deficits cannot be reconciled with hitting the inflation target.'

In the long term, Mr Clarke offers to do better. Next year he expects to get his bor- rowing down to £400 million a week, and not long after that he hopes to kick the habit altogether. He always has hoped that. Every year the Treasury's graph of public borrowing shows an amazing improvement on the right-hand side, in the area distinguished by a light blue tint. The tint stands for projections. On Mr Clarke's original projections, this week's Budget would have been more or less in balance.

What is the matter with his arithmetic? By this stage of the recovery, tax revenues ought to be rolling in — but they aren't — and the demands on the state's benevo- lence ought to be tailing off — but they aren't. The yield on Value Added Tax has disappointed him and baffled his experts. His response is to hire some more tax gatherers, and his projections for the bil- lions of extra revenue they will bring in are the most implausible figures in the whole of his Budget.

It does not seem to cross his mind that he and his predecessor have raised VAT to a level where it is well worth getting round. If one way round is blocked, human inge- nuity will find another. It will happen — it has obviously happened — with benefits, too. Milton Friedman has compared our present system of relieving need to throw- ing banknotes at a barn door in the hope that some will get through the knotholes. It will not be much improved by posting monitors outside the barn.

It will take a reforming Chancellor to think in terms of making taxes what Nigel Lawson said they should be — low, simple and compulsory. Mr Clarke is not in that sense a reforming Chancellor. His instinct is to dream up new taxes (on airline tick- ets, on insurance premiums) and fiddle about with them when he has got them. The taxes on savings are a jungle that awaits a Chancellor with a machete. Mr Clarke ducks away from them, pleading that he cannot afford a slash at Capital Gains Tax or more than a perfunctory slash at Inheritance Tax. Neither of these tangled taxes yields as much as the penny he cut off the Income Tax.

The best joke in his Budget was his invi- tation to his predecessor, Geoffrey Howe, to rewrite the tax code in plain English. Mr Clarke compared this with translating War and Peace into Swahili. Plain English was never Lord Howe's forte as Chancel- lor, and some of his speeches might have been written in Swahili and imperfectly translated. Perhaps he will tell Mr Clarke that it is the code that needs simplifying. Then the language will look after itself. Now reform will have to wait until after the election. Mr Clarke has been saying loud and clear that the election can be won for his party and that he is the man to win it. Punctuated as it was by hoots and grunts and grimaces, his Budget speech seemed to have wandered away from a contentious evening on the stump, and its punch-line made the point: 'It is a Budget that this Government will build upon in 12 months' time.'

In 12 months' time interest rates will be higher than they are now, as signs of an overheated economy become more evident. It would be easier to manage if the Gov- ernment as borrower would get out of its way. One way or another, that is likely to be another Chancellor's worry.

Mr Clarke took his own bravest decision early on. He chose to put the public finances in order and to take the conse- quences. He faced a deafening chorus of anxious whinges, led (as usual) by the Con- fereration of British Industry, who told him that if he put taxes up he would sail into uncharted waters and abort the recovery. Some abortion. The recovery is now in its fifth year and bursting out of its clothes. As for the public finances, they still need to be put in order, but even after three and a half years in office, Kenneth Clarke as Chance!- ]pr represents represents a refreshing change.

Previous page

Previous page