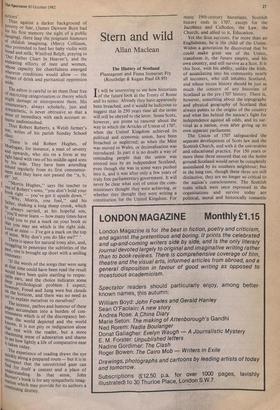

Things past

Rosemary Pavey

Destiny Obscure: Autobiographies of Childhood, Education and Family from the 1820s to the 1920s

Edited and Introduced by John Burnett (Allen Lane £9.50)

D im Andrews closes her brief autobin- I-J graphy with a quotation front Kirkegaard: 'Life', she writes 'can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards'. The retrospective glance of age upon its youthful years remains coloured by the accumulation of its experience and grants, even to bitterness or nostalgia, a degree of detachment. So, I am reminded on putting down this book, lies the ease with reading. Immediate impressions become tempered by those which surround them and at the close of a work one can be surprised l' edrised to find them so differently a John Burnett has collected together the writings of more than 800 men and woolen, mostly from amongst the working or lower middle classes: 'recollections of early childhood' which present a haunting ae- count of social conditions in the previous. century. From these, 28 narratives, at)te° extensively, depict domestic life and ecin

li .ea-

on: a sequel to his portrayal of working life in Useful Toil. But they have apPealli°t only for the historian and sociologist, though they lessen an important gap in th,e, researches of scholars. As John Burtle'' points out, the voices of children are eo; spicuously lacking from the past. Those (1 their parents, whom the exigencies of 'O, drove beyond the consolation of writing le; ters and diaries, are similarly rare. But here are the leisured recollections of both, ten for posterity, for their own children, 1' the enlightenment of the spirituallY unredeemed or the regardless fortunate.: The satisfaction of desire for knowledge °. their immediate promise, but they snb.se quently press upon the mind that widentae curiosity that is the daemon of the awaken ed spirit. Proust once observed: 'We feel quite trti" ly that our wisdom begins where that of t author ends, and we would like to have 1.1111; give us answers while all he can do is give us desires'. (That from Proust, unrivall. amongst autobiographers in his search I.ott; precision!). John Burnett recognises,„ much sensitivity, this relationship betwee.: reader and author. Failure in ability of clic) pression, or natural diffidence, social tab.° or prejudice which forestall the description.;; of certain parts of life, become of themselves powerful unwritten elements history and endow writing with living ef- fect. According to Robert Louis Stevenson 'No man was ever so poor that he could or press all he has in him by words, looks u`

actions' .

Thus against a darker background of Poverty or fear, (James Dawson Burn had for his first memory the sight of a public hanging), there leap the poignant humours of childish imagining. (Mercy Collisson, who pretended to feed her baby violin with bread and milk; Winifred Relph, praying to Our Father Chart In Heaven'), and the

endearing efforts of men and women, whose capacity for cheerfulness emerged wherever conditions would allow — the threats of drink and puritanical oppression aside.

The editor is careful to let them float free of restricting categorisation or theory which

Might damage or misrepresent them. His commentary, always scholarly, just and sympathetic, is never obtrusive so that a sense of immediacy with each account re- Mains undiminished.

Thus Robert Roberts, a Welsh farmer's son, writes of his parish Sunday School Class:

„;There is old Robert Hughes, of "loelogan, for instance, a man of seventy upwards, who sits on a form at my kugnt. hand with two of his middle-aged sons vy, his side. They have been attending school regularly from its first commence- ment and they have not passed the "a, b, al)" Yet.

"Morris Hughes," says the teacher to 211e of Robert's sons, "you don't hold your book right — you've got it upside down." WhY, Morris, you fool," said his hatner, shaking a long sheep crook, which e always carried, at his hopeful son,

You'll never learn — how many times have that You to put a mark on your book so

llat you may see which is the right side. 00k at mine — I've got a mark on the top 'nine. Why don't you do like me?" There is space for natural irony also, and, struge-8 Past lin to penetrate the subtleties of the , one is brought up short with a smiling comment:

If the words of the songs that were sung at that time could have been read the result twould have been quite startling to respec- pheeP ie ears, and the choice indicates some

Psychological problem I expect; 02w,ever, Freud and Jung were but clouds ," tne horizon, and there was no need as 'et to explain ourselves to ourselves!' s'The interest, pathos and humour of these C.ges accumulate into a burden of con- woosness which is of the discrepancy bet- eenthe world depicted and the world 11.1°Nlin. It is not pity or indignation alone ,,at rest with the reader, but a more chastening sense of admiration and shame on see how lightly a life of comparative ease Is taken today.

uietThe experience of reading draws the eye q.

^1Y along a prepared route — but it is in et r°sPect that the unrestricted gaze can and for itself a context and a place of nderstanding. In that sense, John

iunttrnett's book is for any sympathetic imag-

ination which may provide for its authors a continuing destiny.

Previous page

Previous page