LABOUR'S REAL MR FIXIT

A profile of Alastair Campbell,

Tony Blair's PR man, who makes

Sir Bernard Ingham seem like a softie

THE PRESS'S obsession with the Labour Party's team of spin doctors has inevitably led it to conclude that Tony Blair's top bowler is Peter Mandelson. We read end- lessly about the Labour MP for Hartlepool being a wily fixer, a smooth operator behind the scenes, a mixture of Machiavelli and Cary Grant. Parliamentary journalists who write this tosh know it's tosh, but they want us to believe it because it serves their own interests.

By portraying politics at Westminster as an impenetrable conspiracy, they convince the public that they, and they alone, have the inside track. It proves the value of their privileged access. It purports to suggest that they are clever chaps — they see through even the craftiest of politicians and that they aren't swayed or fooled by anyone.

Instead, they have been fooling us. Man- delson may exhibit the guile of the classic leg-spinner, but his role is far inferior to that of Tony Blair's most potent weapon: Alastair Campbell. His official title is press secretary and he is the real powerhouse of New Labour's side. Rather than a spinner, Campbell is more of a front-line opening fast bowler, an intimidating player in the mould of Fred Trueman or Harold Lar- wood.

Not for Campbell the quiet word in the journalistic ear, but an ear-bashing. He harangues journalists he believes to have undermined his cause. And he doesn't care if they like him or not. His primary aim is to see Blair as prime minister and he treats his job with missionary zeal. He regards anyone who gets in the way of his single- minded ambition — whether editor, jour- nalist, television interviewer, Labour MP, party stalwart, old comrade, whoever — as a fair target for his bouncers, beamers and yorkers. There is no sign of a slower ball.

For some reason, journalists confronted by this uncompromising approach rarely write about it. Perhaps they are embar- rassed, since it spoils the image of politics they wish to purvey. Perhaps they are bid- ing their time. However, the BBC's Nicholas Jones has shed some light on the Campbell technique. He received a public dressing down from Campbell at the last Labour conference for suggesting in a tele- vision report that Blair's deputy, John Prescott, might not share the leader's enthusiasm for rewriting Clause Four. A red-faced Campbell assured Jones loudly that Prescott had been 'fully on board every step of the way' and had 'helped in every possible way'.

Six months later, Prescott admitted in a television interview that he had 'very much disagreed' with the change to Clause Four at the time. So, as Jones comments, he now sees Campbell's tirade for what it was: a 'snow job' to mask the truth. In journalistic circles, such stories of Campbell's explosive evasiveness are common currency.

But the latest has shocked even those used to Campbell's bluster. The Guardian published a secret memorandum to Blair from public relations adviser, Philip Gould, which suggested that the party was 'not yet ready for power'. It was an embarrassing leak for Labour, revealing the way in which Blair depends on a small coterie of aides.

Alan Rusbridger, the Guardian's editor, was summoned with the paper's political editor, Michael White, to a kind of summit meeting with Blair and Campbell to clear the air. The mild-mannered Rusbridger stood his ground. A story was a story. But Campbell, an experienced journalist, had been pre- pared for that. Together with Blair, he recited a long list of other Guardian arti- cles which he claimed had been anti- Labour. Campbell demanded 'loyalty'. Rusbridger argued that his paper was doing its job as an independent voice. The meeting broke up with Rusbridger being described as a 'pompous public-school prat'.

This farcical meeting was perhaps Camp- bell's first reverse. In March of this year, he forced the BBC to delay the screening of a Panorama interview with John Major, on the pretext that it might affect local elec- tions. Now he has attacked a provincial evening paper: he is demanding that the Birmingham Post apologise for falsely claiming that Blair suggested the party should be renamed the Social Democrats. The Post's editor is refusing because, he says, the evidence is on tape.

Campbell is also at war with the Sunday Telegraph which revealed that John Prescott was excluded from a secret strate- gy meeting held last March. Campbell countered by saying that the meeting was merely arranged to 'introduce' Blair to Chris Powell, chief executive of Labour's advertising agency, Boase Massimi Pollit. But the Sunday Telegraph discovered that Powell and Blair had known each other for ages. The Labour reply? Blair was being introduced to Powell's ideas. As the paper pointed out, this is economy with the truth.

Campbell, 38, is the classic poacher turned gamekeeper, a journalist trans- formed into a political PR man. But the change is not as stark as it seems. Even as a political editor at the Daily Mirror and Today, Campbell was first and last a propa- gandist for the Labour Party. His energy, commitment, determination — allied to acute political antennae — make him a formidable force in Blair's camp. He is tall, though not well built, but he has the ability to frighten. His anger is fearsome and it doesn't seem to take much to provoke him.

At the back of many journalists' minds is the knowledge that Campbell did once lash

out. Just after Robert Maxwell's death, in a

spasm of misguided loyalty, Campbell punched the Guardian's Michael White for insulting the memory of his recently drowned employer (`Bob, bob, bob'). But at least Campbell didn't punch Michael White again during the summit meeting with the Guardian.

It would be a mistake to view Campbell's lack of subtlety as symptomatic of a lack of intelligence. He combines a shrewd politi- cal brain with his brawn. He knows just what he is up to. His fierce assaults on his former colleagues are part of a strategy designed to create a New Media for 'New Labour'. Nothing has been left to chance in an extraordinarily professional campaign to counteract traditional newspaper hostility.

Campbell's analysis of the last election is that the press played a crucial role in turn- ing floating voters against Neil Kinnock, not only in the final weeks and days but, most importantly, in the years beforehand. Readers were predisposed to mistrust Kin- nock because he had been debunked as 'a Welsh windbag' with a suspect intellect. Even though Blair is generally regarded as more saleable and voter-friendly than Kin- nock, Campbell cannot countenance failure in 1997.

So Campbell set out to win the press around. The most fervent and influential Tory papers must, at the very least, be neu- tralised: hence the tactic of Blair cosying up to Rupert Murdoch, which has already paid dividends. Campbell has negotiated the publication of several articles by Blair in the two best-selling tabloids, the News of the World and the Sun. He has also judi- ciously arranged 'exclusive' interviews with all five of the Wapping titles. The Labour press, which means the Mirror Group titles, have fallen happily into line.

But this charm offensive has not been good enough by itself, especially for the rest of the press and broadcasters. This is where the second strand of Campbell's strategy comes in, requiring his own special brand of personal confrontation. He com- plements the public ingratiation, which is his leader's natural style, with a private ferocity against all who stand in Blair's path.

The instant the first editions roll off the presses, Campbell and his team scan every political story. They listen to every televi- sion and radio broadcast. Anything written or said which Campbell deems not to be in Blair's best interests is noted: factual mis- takes, supposed bias in interpretations, nuances of emphasis. Then Campbell gets to work. Statements are issued, story sources are contacted (woe betide a Labour MP who has been quoted saying something which Campbell believes to have been 'unhelpful), correspondents are called.

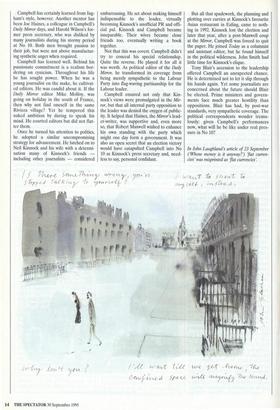

But it's the eyeball-to-eyeball confronta- tion between Campbell and an offending journalist the next day which is his trade- mark. Bernard Ingham, Mrs Thatcher's plain-spoken and temperamental press aide, was an old softie compared to Camp- bell. He hectors, cajoles and shouts every bit as loudly as in the days before he foreswore the demon drink. And he doesn't care if anyone is listening either. The effect, as he knows well, is to ensure that the browbeaten journalist thinks twice in future — and that might make all the difference. ► 'Product placement has gotten so obtrusive.' Campbell has certainly learned from Ing- ham's style, however. Another mentor has been Joe Haines, a colleague in Campbell's Daily Mirror days, and Harold Wilson's for- mer press secretary, who was disliked by many journalists during his stormy period at No 10. Both men brought passion to their job, but were not above manufactur- ing synthetic anger when required.

Campbell has learned well. Behind his passionate commitment is a realism bor- dering on cynicism. Throughout his life he has sought power. When he was a young journalist on the make, he cultivat- ed editors. He was candid about it. If the Daily Mirror editor Mike Molloy, was going on holiday in the south of France, then why not find oneself in the same Riviera village? Yet he tempered this naked ambition by daring to speak his mind. He courted editors but did not flat- ter them.

Once he turned his attention to politics, he adopted a similar uncompromising strategy for advancement. He latched on to Neil Kinnock and his wife with a determi- nation many of Kinnock's friends including other journalists — considered embarrassing. He set about making himself indispensable to the leader, virtually becoming Kinnock's unofficial PR and offi- cial pal. Kinnock and Campbell became inseparable. Their wives became close friends too, eventually writing a book together.

Not that this was covert. Campbell didn't try to conceal his special relationship. Quite the reverse. He played it for all it was worth. As political editor of the Daily Mirror, he transformed its coverage from being merely sympathetic to the Labour Party into flag-waving partisanship for the Labour leader.

Campbell ensured not only that Kin- nock's views were promulgated in the Mir- ror, but that all internal party opposition to the leader was denied the oxygen of public- ity. It helped that Haines, the Mirror's lead- er-writer, was supportive and, even more so, that Robert Maxwell wished to enhance his own standing with the party which might one day form a government. It was also an open secret that an election victory would have catapulted Campbell into No 10 as Kinnock's press secretary and, need- less to say, personal confidant. But all that spadework, the planning and plotting over curries at Kinnock's favourite Asian restaurant in Ealing, came to noth- ing in 1992. Kinnock lost the election and later that year, after a post-Maxwell coup at the Mirror, Campbell was forced to quit the paper. He joined Today as a columnist and assistant editor, but he found himself in the political wilderness. John Smith had little time for Kinnock's clique.

Tony Blair's accession to the leadership offered Campbell an unexpected chance. He is determined not to let it slip through his hands again. Yet some journalists are concerned about the future should Blair be elected. Prime ministers and govern- ments face much greater hostility than oppositions. Blair has had, by post-war standards, very sympathetic coverage. The political correspondents wonder tremu- lously: given Campbell's performances now, what will he be like under real pres- sure in No 10?

In John Laughland's article of 23 September (Whose money is it anyway?) 'fiat curren- cies' was misprinted as 'flat currencies'.

Previous page

Previous page