Religion

Rediscovery

Martin Sullivan

The New Testament makes it quite clear that in most matters Christ's -immediate disciples, i.e., the Twelve, either misunderstood Him or could not grasp what He told them. They were not naturally religious men, not intuitive or mystical. They possessed no special qualifications, social position or education. They had been fishermen, tax-collectors, and one of them, Simon the Canaanite, was possibly an anarchist. They were not clergymen and they were not theologians, a fact which sometimes seems to have escaped the notice of ardent churchmen. I mention these matters because there seems to be a notion abroad that if we could only get back to this early period, we could then have some genuine statements clarifying the Christian faith once and for all. We would be gravely mistaken. Those who advance this argument have overlooked the evidence of the New Testament itself to which I have earlier referred. It would be tedious to particularise, but the evidence abounds. Again and again Christ patiently corrected the wrong interpretation his friends put upon his sayings and actions. Even the point of some of His parables escaped them, as some of their

sententious editorial footnotes disclose. But there was one great issue about which they were sadly mistaken, and indeed there are many scholars who say that Christ Himself shared in their error. They expected His second coming to be imminent and they had definite views about the nature of it. They visualised a Messianic Kingdom in Palestine consisting of all the saints, to be established by Jesus upon His return. This view died hard, and when eventually it disappeared, as it was obliged to do when the Second Advent failed to materialise, the whole scenery and trappings of the theocratic kingdom were transferred from earth to heaven and from the near to the distant future. For two generations at least these illusory pictures were retained. For many modern Christians they are still the symbols of the world to come, and they have been lifted across the centuries 'without any critical examination of them at all.

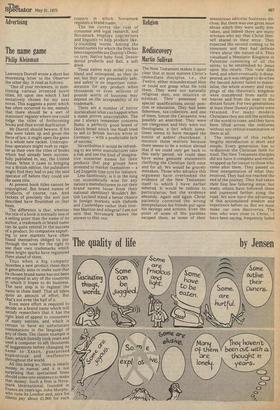

The message of this rather lengthy introduction is short and simple. Every generation has to re-discover the Christian faith for itself. The New Testament disciples did not have it complete and entire, wrapped up for transit to those who came after them. They passed on their interpretation of what they received. They had not reached the end of the journey. They had taken their first few faltering steps; but many others have followed them and journeyed farther along the road. We now have the advantage of this accumulated wisdom and experience before us. But we must make our own discoveries. The men who were close to Christ, I have been saying, frequently failed to understand Him; but, of course, they had their moments of truth. Nevertheless, their moments are not necessarily ours, nor are those of people in the tenth century, or the fifteenth, or even at the beginning of this one. As one of our great theologians, speaking of the first disciples, has put it, 'What must the truth be and have been if it appeared like that to men who wrote and thought as they did?' And that means, if people who thought and lived as these people long ago thought and lived, if that is how they saw the truth, then what must it mean for us in terms of our thought and experience!

What does the parable of Dives and Lazarus demand of Christians who look out on the hungry, homeless third world? The lesson is razor-edged. Dives was condemned because he did nothing. And the Good Samaritan spells it out again take all the risks involved in helping my stricken neighbour?' but, 'what will happen to him if I do not come to his aid?' A church which for generations not only condoned but supported slavery, does not help us if we go back and sit where its members sat. We are to set out to find answers in our time, and if the back of history is broken as we are en route, that itself will be only another revelation, albeit the final, of what we are seeking.

Martin Sullivan is Dean of St Paul's

Previous page

Previous page