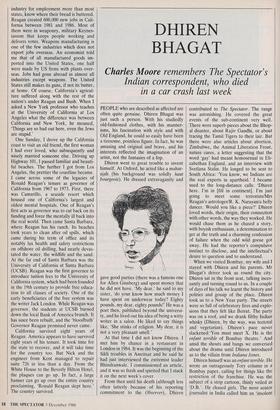

DHIREN BHAGAT

Charles Moore remembers The Spectator's

Indian correspondent, who died in a car crash last week

PEOPLE who are described as affected are often quite genuine. Dhiren Bhagat was just such a person. With his studiedly old-fashioned clothes, with his manner- isms, his fascination with style and with Old England, he could so easily have been a tiresome, pointless figure. In fact, he was amusing and original and brave, and his interests reflected the imagination of an artist, not the fantasies of a fop.

Dhiren went to great trouble to invent himself. At Oxford, he acted like a mahar- ajah (his background was solidly haut bourgeois). He dressed extravagantly and

gave good parties (there was a famous one for Allen Ginsberg) and spent money that he did not have. 'My dear,' he said to my sister, 'do your know how much money I have spent on underwear today? Eighty pounds, my dear, eighty pounds!' He was a poet then, published beyond the universi- ty, and he lived out his idea of being a witty writer in a salon. He liked to say things like, 'She stinks of religion. My dear, it is not a very pleasant smell.'

At that time I did not know Dhiren. I met him by chance in a restaurant in London in 1984. It was the beginning of the Sikh troubles in Amritsar and he said he had just interviewed the extremist leader Bhindranwale. I commissioned an article, and it was so fresh and spirited that I stuck it on the next week's cover.

From then until his death (although less often latterly because of his reporting commitment to the Observer), Dhiren contributed to The Spectator. The range was astonishing. He covered the great events of the sub-continent very well. There were superb pieces about the Bhop- al disaster, about Rajiv Gandhi, or about tracing the Tamil Tigers to their lair. But there were also articles about abortion, Zimbabwe, the Animal Liberation Front, nature cures, a letter suggesting that the word 'gay' had meant homosexual in Eli- zabethan England, and an interview with Svetlana Stalin. He longed to be sent to South Africa: 'You know, we Indians are the real experts in apartheid.' I became used to the long-distance calls: `Dhiren here. I'm in [fill in continent]. I'm just going to meet some terrorists/Mrs Reagan's astrologer/R. K. Narayan/a belly dancer. Would you like a piece?' Dhiren loved words, their origin, their connection with other words, the way they worked. He would chase them as he chased a story, with boyish enthusiasm, a determination to get at the truth and a charming confession of failure when the odd wild goose got away. He had the reporter's compulsive instinct to disclose, and the intellectual's desire to question and to understand.

When we visited Bombay, my wife and I stayed with Dhiren and his parents. Mr Bhagat's driver took us round the city. Dhiren sat in the front seat, talking inces- santly and turning round to us. In a couple of days of his talk we learnt the history and politics and gossip of the place. Dhiren took us to a New Year party. The streets were so full of celebratory fires and explo- sions that they felt like Beirut. The party was on a roof, and we drank filthy Indian whisky (Dhiren, by the way, was teetotal and vegetarian). Dhiren's pace never slackened:`You must meet X. He is the enfant terrible of Bombay theatre.' And amid the shouts and bangs we conversed about the drama until Dhiren introduced us to the villain from Indiana Jones.

Dhiren himself was an enfant terrible. He wrote an outrageously Tory column in a Bombay paper, calling for things like the restriction of the franchise. He was the subject of a strip cartoon, thinly veiled as `D.B.'. He chased girls. The most senior jburnalist in India called him an 'insolent

puppy'. He got very over-excited. Once we sat in the flat with his parents. His devout mother was silent. His father, a deep- voiced, kindly, worldly man argued with his son: 'No, no, my boy —"With respect, sir,' shouted Dhiren, his voice rising almost to a squeak, 'you are WRONG.'Boys, boys,' exclaimed his mother, and Dhiren simmered down reluctantly, like a clever child of 12.

Like many Indians fascinated by this country, Dhiren was utterly unEnglish. The English intoxicated rather than calmed him. For me and many others, he made India fascinating in return. He was an embodiment of one of the strangest rela- tionships between two nations that the world has ever known. If he had lived (he was only 31), he would have become a better and deeper writer still. He was dear to me, and the loss of one so young and so unusual is terribly cruel.

Previous page

Previous page