On the side of the angels

Richard Shone

BERTHE MORISOT: THE FIRST LADY OF IMPRESSIONISM by Margaret Shennan Sutton Publishing, £14.99, pp. 342 Few paintings by Berthe Morisot are Widely familiar, the best known being 'The Cradle' in the Musee d'Orsay, a depiction of watchful motherhood, and the London National Gallery's quintessential summer idyll of two smart young women in a boat. But Morisot's face is world-famous from the several portraits of her by Manet (her future brother-in-law). Her hypnotic pres- ence in his masterpiece 'The Balcony' is pest known of all: she leans against the Veen railings, her magnetic dark eyes gaz- ing into the near-distance. In her white silk-organza gown, fan in hand and lapdog eager for her distracted attention, she is the epitome of mid-19th-century refine- ment, raised one storey above the rough and tumble of life. , This image, however, is only partly true. Mx was indeed a lady, unashamedly obser- vant of the social niceties of the grande bourgeoisie into which she was born. She was moderate in politics, conservative in morality, descriminating in her taste. Yet, at the same time, she belonged to the most radical and ridiculed movement in art of her period and never wavered in her com- mitment to its tenets and to the work of /Janet, Monet, Renoir and the other Impressionists. As a woman, Morisot's eTranitment was doubly dangerous: many (3' the reviews of the First Impressionist exhibition of 1874 were condescending in the extreme to this lone female dissident. tither critics overpraised her by exempting her from the radicalism of her fellow- exhibitors on account of her 'charming, feminine grace'. Yet others maintained that her sketchy manner of painting was eel,. mmensurate with the expected dilettan- tism of her sex and class. . Morisot was used to such indulgence and "o the scepticism shown by others over her '-telosen profession. It only toughened her rshsolve and, as we see from her letters, her a_arP intelligence rapped on the door of decorous, early floating indecision. Beneath her inice,r°1-1s, often silent surface, she could be n_Pineable. As her friend Paul Valery "led, the seriousness of her demeanor was at times inflected 'by a certain smile on the lips alone — which dismissed people who did not matter with a hint of some- thing they might have reason to fear'.

Through the 1860s, Morisot's resolve to be an artist was strengthened by her friend- ship with Manet, the most innovative painter in France. Posing for him, attend- ing his studio, absorbing his advice and amused by his exhilarating canards, she rapidly matured. It was an incomparable education; there was no going back. Natu- rally, she fell in love with this urbane, buoy- ant, handsome but married man. The situation was partly resolved by her mar- riage, a few years later, to Manet's brother Eugene, not even second best. When he died unexpectedly in 1892, it was with self- reproach that she surveyed their 18 years together — years of companionship and tolerance and parenthood but, for her at least, never of love. Something of this painful realisation enters her last self- portraits before her own premature death in 1895.

Margaret Shennan is a most sympathetic biographer and the paperback reissue of her book should bring Morisot's difficult and entrancing character to a wider public. It is far less poutingly gender-bound than Anne Higonnet's readable biography of 1990. It is judicious and inquisitive. She delicately suggests the tensions and frustra- tions of Morisot's life, balancing her gaiety and melancholy, setting the sensuous self- absorption of the painter against the woman capable of sudden crushing, ironic phrases. She is good on Morisot's decisive but unmeddlesome interventions in the his- tory of the Impressionist exhibitions (she showed in seven out of eight of them) and gives an enticing picture of her central position in a section of Parisian cultural life, where she won the devoted admiration of Renoir, Degas, Monet and Mallarme.

In spite of scholarly apologists and recent exhibitions, Morisot is still under- rated or, at least, misunderstood. Undoubt- edly the circumscribed nature of her sub- ject matter — sun-flecked gardens, women, children (above all her beautiful daughter Julie, truly a jeune fille en fleur) — makes a certain kind of critic indifferent; others wallow in this refined, feminine world at the expense of Morisot's artistry. Her descendants, until recently parsimonious in releasing her work, have not always helped in its dissemination and evaluation; and her reputation has sometimes been pushed aside by that of her ambitious Impression- ist colleague, the American Mary Cassatt (whose achievements have been grandly re- assessed in a recent book by Griselda Pol- lock, the foreword-writer of Shennan's biography). It is time Britain, in particular, saw a full retrospective of this great Impressionist. The Royal Academy has served her colleagues well with shows of Monet, Pissarro and Sisley. Now surely it is Morisot's turn.

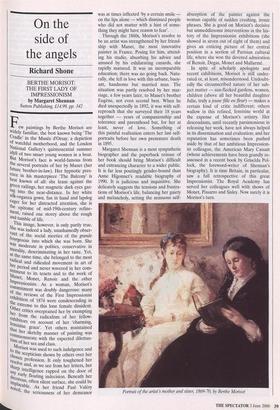

Portrait of the artist's mother and sister, 1869-70, by Berthe Morisot

Previous page

Previous page