Fame and fortune

Sarah Jane Checkland on the effect of Young British Artists commanding such huge prices Time was when the Tate Gallery ignored the existence of the avant-garde. It took a campaign by the artists Henry Moore and Ben Nicholson to persuade the trustees to buy their first Picasso in 1933, and even then the gallery opted for the tamest example on the market: a flower piece from 1901.

Nowadays, the opposite principle applies. The new Tate Modem veritably bursts with works by young artists, acquired within a year of their making. Examples include Sarah Lucas's 'Chicken knickers' of 1997 (a photograph of a female torso with the afore- mentioned bird attached where the puden- dum would otherwise be); Mona Hatoum's `Untitled' of 1998 (a hospital wheelchair designated 'are by her in 1998), and Damien Hirst's 'Forms without Life' — a cabinet full of shells of 1991. But their inclusion only begs the question: why are we not being treated to the more memorable efforts of their generation? Where are Tracey Emin's grubby sheets and condoms, and Damien Hirst's pickled or maggoty beasts?

The omission cannot be due to the issue of conservation as the Tate has cheerfully taken on such challenges as Joseph Beuys's lumps of animal fat. Likewise a mural by Sol LeWitt has been painted afresh by techni- cians, according to instructions laid out in a kit supplied by the artist, so it is clear that a trip down to the dump or abattoir to find fresh supplies would be all in a day's work. Furthermore, it cannot be said that the Tate does not rate these artists: their very own panel awarded Hirst the Turner Prize in 1995 while Emin was on last year's shortlist. Could the grim truth be that, having aided and abetted the priciest mar- ket for contemporary art ever known in Britain, the Tate simply cannot afford to buy? Hirst's latest work — a 20-ft statue based on a tiny £14.99 Humbrol toy — had a price tag of £1 million, while Emin's bed is for sale at £200,000.

This unprecedented state of affairs results from a complex, and much aired, series of events, beginning in 1991 when Hirst, aspiring unknown and son of a car salesman, met the young dealer Jay Jopling in a pub and together they started dreaming up schemes. Soon the drawing that Hirst had made of a shark in a case had not only become a reality, but had found a niche in the collection of the advertising mogul Charles Saatchi, who bought it for £45,000. Jopling then proceeded to assemble an entire stable of like-minded artists, and to leak to the media their tales of derring-do. Saatchi, meanwhile, became their main col- lector, basking in the reflected glory and near-monopoly market over which he presided.

And so matters might have continued, with everyone concerned being successful and fulfilled, until the art establishment began to take an interest in our Young British Artists, or YBAs as we now fondly call them. First, Hirst got his Turner Prize, then Norman Rosenthal, exhibitions supre- mo at the Royal Academy, put on a show by Saatchi artists in 1998 called Sensation.

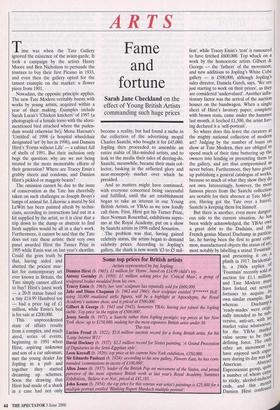

The problem was that, having gained celebrity status, the artists began to demand celebrity prices. According to Jopling's gallery, the shark is now worth 13 to £5 mil- lion', while Tracey Emin's 'tent' is rumoured to have fetched £600,000. Top whack on a work by the homoerotic artists Gilbert & George — the 'fathers' of the movement, and new additions to Jopling's White Cube gallery — is £500,000, although Jopling's sales director, Daniela Gareh, says, 'We are just starting to work on their prices', as they are considered 'undervalued'. Another infla- tionary factor was the arrival of the auction houses on the bandwagon. When a single sheet of Hirst's lavatory paper, complete with brown stain, came under the hammer last month, it fetched £1,500, the artist hav- ing declared it a 'self-portrait'. So where does this leave the curators at the mighty national collection of modern art? Judging by the number of loans on show at Tate Modem, they are obliged to spend much of their time buttering up the owners into lending or presenting them to the gallery, and are thus compromised as never before. Furthermore, they have given up publishing a general catalogue of works, because so much of what they show they do not own. Interestingly, however, the most famous pieces from the Saatchi collection are notable for their absence at Tate Mod- em. Having got the Tate over a barrel, Saatchi is keeping them fot himself.

whereas Ducharnp',s `ready-mades' were origi- nally intended to be sub" versive, anti-art, with no market value whatsoever; for the YBAs market value seems to be the defining force. The on,' other art movement 10 _ have enjoyed such exIllie sure during its day was t" t Abstrac American Expressionist group, a number of whom enui, to sticky, alcohol-induc ends, and this 111°11T' Damien Hirst confess° not only to a drink problem, but a creative block which lasted from 1996 until this year. Unless some corrective is inserted into the system, there is a distinct risk that he and his fellow YBAs will be killed by kindness. The time has come to inject a new element of sanity into the market for their works, and the Tate can start by reverting to its earlier policy, buying only after posterity has had some time to judge.

Previous page

Previous page