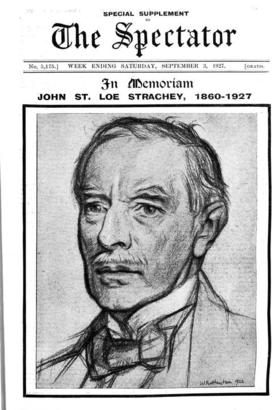

an Memoriam

JOHN ST. LOE STRACHEY, 1860-1927

John St. Loe Strachey

THESE columns are not the place where a writer's personal feelings of affection or grief can decently be exposed ; still less fit are they as a vehicle for sympathy with those for whom he feels it most deeply, for, the greater their loss, the more intimate their grief, the more must their sorrow shrink from the harsh light of publicity and plead for a veil of tender reticence. But even those who cared most for St. Loe Strachey and would most dearly wish to respect the feelings of those who mourn him most nearly, can realize that readers of the Spectator might claim that some who knew him longer or better than most of them could know him, should try to give them pictures of him as he lived. One reason why they may claim it is that probably they have involuntarily formed a picture, although, may be, they never saw his figure nor heard his voice. For seldom can a paper have been more obviously inspired and pervaded by its editor's mind and character than the Spectator was in the years before the War.

As a boy he tasted country life, good talk and literature, and foreign travel. All his life these were his chief joys and occupations, always shared in a closely united family life ; for he was " domestic " by instinct and by habit. The Strachey family has been largely and honourably represented in India since the days of Clive and this widened the family traditions beyond Somerset and quickened his interest in Imperial questions. All these early interests were not affected, for better or worse, by the influence of any Public School life. The first real change was to Oxford, and there, though he made some strong and lasting friend- ships, he neither left much mark nor bore himself signs of • the impressions that she leaves on most of those who benefit by what she gives. His later affection for Oxford seemed one that might have been felt for any home of youth, any place where young minds are bursting from the bud. Yet there was another tie with her. To Oxford his sons were sent from Eton, and there the promise of the elder was cut off by death.

Then came London, the Bar, journalism and the Spectator ; a most happy marriage and family life in Surrey sharing the week with his work in London, with an annual holiday, usually spent abroad. It was an astonishingly vigorous and full life, in which lie yet found tune for a vast amount of varied reading ; old books such as his favourites, the Elizabethans and Pope, translations from the Classics and new books on political or other topical subjects. His activity in politics beyond directing and expressing the views of the Spectator led to his contesting a Scottish University seat as a Unionist Free Trader, but he never had the opportunity of proving himself a successful Member of Parliament. Whatever he did he did with an eager zest that delighted even opponents. He had a wonder- fully open mind that was always ready to find something worth attention from unformed boys and girls or uneducated men and women. Youth and its unbiased opinions always appealed to him. Convention had for its own sake no attraction. Sometimes, when he flouted convention, when, perhaps, he designed and wore a new uniform, it was easy to laugh at him, but those who laughed heartily loved him no less ; if any laughed without affection, they did not understand and do not count. Novelty in anything prejudiced him in its favour unless it was directly contrary to some great principle that he held dear.

In his country life a new method of building was far more enthralling than any sport. He did enjoy hunting, but the riding that he liked best was on a small horse or pony. He always advocated small, cobby horses as best for staying power and sureness of foot. Thus he used to ride about the Surrey Downs exploring new paths Or showing them to the " Surrey Guides " whom he invented in case war should penetrate Southern England.

Yet twenty-five years ago he was also the owner of that novelty, a motor car.

In politics and economics the principle that called out his greatest energy, and whose adVocacy in the Spectator made his influence really important, IN AS- that of free exchange. He made his paper the greatest opponent of Tariff Reform that existed. He enabled the Unionist Free Traders to exert their power and for tile time, at any rate, to kill Protection and Colonial Preference. As for Preference as a policy, he was a great Imperialist in the best sense and felt passionately that to bind an Empire by the bickering and huckstering over tariffs and trade bargains, instead of by nobler sentiment, was both contemptible and mad. His devotion to freedom was not limited to the sphere of trade. He hated the idea of a Socialistic bureaucracy encroaching upon any freedom of the British subject.

That was the most prominent service he did for his country. Another that must be reckoned highly was his work for cheaper building, particularly in rural housing. Then there was his creation of the " Veterans," the registration of trained men who had left the colours. By this it was said without great exaggeration in 1914 that he, a single man, had in effect added 250,000 men to the available forces of the Crown. This brings us to the War, into which he plunged with burning patriotic zeal and unquenchable optimism. To some this optimism seemed exalle or to imply insensibility to the horrors 'of war. Really it was both natural and deliberate. He was always looking to the end of the struggle and determined that his influence should keep up the spirits of his countrymen through the long ordeal. That was no mean service.

To his life up to the War we might apply some lines that he wrote of a friend, who

" Sees his past days safe out of Fortune's pow'r, Nor dreads approaching Fate's uncertain hour : Reviews his life, and in the strict survey Finds not one moment he could wish away, Pleased with the series of each happy day."

But the picture is not complete yet. We would fain that it were, for the years after 1916 were on the whole sad in spite of some bright gleams, sad at any rate to those who love to dwell upon the earlier, truly happy years. .It was plain that the War led him to strain his physical and nervous system beyond human endurance. No proof more grievous to those who cared for him of the severity of the illness that attacked him could be needed than to see him then listless, almost idle day after day. He grew worse and looked death in the face. Then came an unexpected recovery.

We must be thankful for the ten years' respite, for at times the old zest for life seemed to return. He did get pleasure from again actively taking part in affairs, although spasmodically, and there was one unalloyed delight, namely, his last visit to Canada and the United States, of which he enjoyed every minute. But through these years it was not the old St. Loe. By the side of efforts to regain the old eagerness, to be up and doing something new every day, was a new tendency to throw off responsibilities and to make time for rest a wise moderation that pointed out a change. He could Rot count so surely on himself to concentrate the keenness of his brains on forming a far-seeing judgment or to keep the consistency of his views against pressure or persuasion. He was no longer the adept follower of his beloved Halifax in keeping an even keel.

Last spring he sought health in a journey to 'South Africa and came home smitten by a return of the old malady, alas ! not to be overcome this time. The country should long remember gratefully that old St. the Strachey whom death will never.drive out of the hearts or memories of those who knew him best.

Mucus;

John St. Loe Strachey

" AN eager, earnest, pointed spirit." Such was St. Loe Strachey. A naked flame of life seemed always to be burning in him, unshaded by the slightest diffidence, undimmed by the slightest fear. Incapable of languor, -incapable of melancholy, with the restlessness which belongs to zeal—those who remember him as a young man remember hiM as a youth apart.

The second son of a Somersetshire squire, he was not put through the mill, but was brought up chiefly at home, in a fine old house, with, as he was fond of saying, " a largish library." It was hereditary in his family to be unconventional. " Not odd for a Strachey," was said a hundred years ago of one of his ancestors. Not rich enough to do nothing, not poor enough to suffer from the insistent drive of never avoidable labour, the family had mixed professional and aristocratic traditions. India, the Somersetshire countryside, and the Law Courts all came into the crowded background of their

4 ancestral dreams.

His father, Sir Edward Strachey, might have been described as a squire of letters, carrying out what were then considered the duties of a country gentleman, and reading and writing for pleasure. Judging from his son's picture„ he seems to have had an intense notion of the importance of happiness. He dreaded for his boys the rigours of school life as much as he mistrusted the intellectual ideals of the public schools. English literature should be, he thought, the foundation upon which an English boy's mind and character should be formed. St. Loe grew up with a passion for reading, and with hardly any knowledge of Latin or Greek, or indeed of any language but his own. The first piece of luck which came to him in a wonderfully lucky life was his nurse, who used to read him to sleep with the great poets, so that he " dreamed in numbers " before their meaning came to him. A little later he used to get up very -early in the morning, go and sit in " the great parlour" at Sutton, take doiin booki of poetry, preferably Byron or Shelley, and " race through their pages in a delirium of delight." The growth of his mind and imagination upon this intensive feeding was very vigorous, and he tells, in the Adventure of Living, of an experience which occurred to him as a little boy which set a mark upon him for life, and apart from which his character cannot be understood. Standing in the passage outside his nursery at Sutton Court, lie describe-4 himself as suddenly a prey to an overwhelming sensation. He was literally beside himself, " a naked soul in sight of what I must now call the All, the Only, the Whole, the Everlasting."' Into this " All " he had no sense of absorption, " rather it was the amplest exaltation and magnification of Personality that it is possible to conceive." There came to the child " a sudden realiza- tion of the appalling greatness of the issues of living." At the same time he felt himself fully " equal to his fate," not only.immortal, ", but capax imperil; a creature worthy of a heritage so tremendous."

Though his tutors taught him on the lines his father pointed out to them, and though his father was guided by the boy's inclinations and gave him plenty of leisure to scour the country on a pony, in no sense of the phrase did he and his brothers ever run wild. His father showed them an example of fine manners, and his mother, a sister of John Addington Symonds, and a woman who made an art of life, studying both to please and be pleased, - " added that burnish without which good manners lose half their power." At Oxford he was from first to last supremely happy, though by his own account the Dons never liked him, never had a kind word for him. They never forgave his unconventional education, though his fellow-students seem not to have troubled in the least about his unschooled condition of

mind. . - A little later on, when he had left Oxford behind him, the charm of his personality seemed quite irresistible to men of an older generation. They warmed both hands at the flame of his vitality, and listened spellbound to the flow of his talk. Young people, however, looked at him more critically. They thought he placed himself in the limelight, in a manner to throw other people into the shade, not always recognizing, as their fathers did, that the light shone from his own personality, so that he could not help being conspicuous.

From 1886 onward the Spectator became the pivot of his life. Long before his position on the Paper was known to outsiders, while he was still only writing weekly leaders, .and " supplying," for each editor in turn, he knew that the Spectator would eventually be his. Richard Hutton and Meredith Townsend, among their intimates, spoke of him as the heir-apparent, before he had completed his first year's work: The story of his instantaneous conquest of the hearts, one might almost say of the wills of these two middle-aged men, not given to " take fancies," is drainatically told in his autobiography, Wherein he pays to his two old editors a most noble tribute.. When, after some dozen years of apprenticeship, their mantle fell upon him, he carried on the Spectator upon their lines, with a difference. He knew the world as they never knew it. His marriage, his gifts, and his amazing luck brought him into contact with all the famous men of his day, and through his wife's mother, a daughter of Nassau Senior, he imbibed, at first hand, the tradition of all the 'earlier men of distinction—a fortune indeed for a journalist.

We are still too near the War to make it necessary to remind our readers how patriotic was the part that he played in it. After it was over, he never stirred from his conclusion that it was inevitable. He refused, as he said, to apologize for it in any shape or form. He was intensely proud _of it, and if such a thing may m be said without 'sinister meaning, he intensely enjoyed it. For St.. Loe Strachey the dramatic element in life -could never be eliminated. It enhanced its triumphs, it softened its tragedies. He saw life, not out of the window as a bare 'reality, 'bust in that mirror which the dramatic imagination holds up to nature. That is only to say that he was it great journalist.

The War ruined his health, but he took that ruin in

perfect good part, still determined to one life, still believing in his luck. Certainly, in one very serious particular, his faith bore him out. During a period full of political crises, when he was too ill to edit, he had Mr. J. B. Atkins standing at the helm of the Paper. No smiler had the doctors proclaimed .him out of immediate danger, than he began to work again. " I am but of the condemned cell now," he said gaily to the present writer, adding with all his old eagerness and earnestness, " but, you know, it's not so bad in there." .

A word should perhaps be said about his attitude to theology. He was content to remain within those stately precincts of English Broad Churehisni whose windows give upon the sunnier side of doubt. These words from his autobiography show how lie expected to meet death :—

" I who have always been an explorer at heart am getting near the greatest exploration of all. There are only two or three more bends of the stream, and I shall shoot out into that lake or new reach; whichever it may be. I may have a pleasant thrill of dread of what is there, but not of fear. The tremendous nature of that splendid unknown may send a shiver through my limbs, but it is stimulating, not paralyzing."

Apart from the sorrow of those who loved him, the sense of loss at his death is a curiously poignant one. His figure looms very large in the memory of even his least intimate friends. It is difficult to describe him, they will say, to those of his readers who never saw him in thc. T. the flesh, because there never was anyone like him. John St. Loe Strachey "The Adventure of Living: A Subjective Autobiography. By John St. Loe Strachey, Editor of the Spectator."

A BRIEF " lustre," five years, no more, ago, when the striking volume thus described and designated was given to the world, this was the vivid description of the book and of its vivid writer. It was then the epitome of an unusual character and career. To-day, alas ! it is their epitaph. The adventure of living is over, the tale is told, the eager spirit has run its breathless course and fallen at the goal, its curious, questioning contem- plation of itself has passed out of knowledge and expression ; " the rest is silence." Only the written epitaph now remains " after the vanished voice and speaks to men." More than ever every word of it tells, the title and the sub-title of the self-written record ; his very names, too, John St. Loe (John de Sancto Lando), with all their associations ; his official style, the blason, the heraldic recital, of his achievement.

To one who has known and loved him from his boyhood, it is strange to look back over all these long, yet hurrying, years and to attempt to sum them up.

He has himself told his story so .that its telling cannot be bettered. He was a great journalist, but great in his own individual way. He wrote for the Saturday and the Observer, the Standard, the Daily News, the Man- chester Guardian, the Academy, the Pall Mall, the Economist, the Cornhill, the Quarterly and the Edinburgh. Of the Econoinist and the Cornhill, for a few years, he was editor. Of the Spectator for many years he was editor and proprietor also. It was, as he said, " the pivot of his life."

He was born for adventure, born, it would seem, for the Spectator. He had " the supreme luck," in his own phrase, to be the second son of a Somersetshire squire, brought up in an old manor house in that green western region where romance still haunts the countryside.

The early Stracheys were Elizabethan, friends of Campion and Ben Jonson, acquaintance perhaps of Shakespeare ; they took on new bents and bias in specu- lation and action in the seventeenth and eighteenth century as Locke and Clive, Burke and Hastings, Fox and Shelburne, Byron and Nelson, Pitt and Liverpool, swam into their ken and affected their orbit.

Strachey's father, born between Trafalgar and Waterloo, was a delightful elderly father as I remember him ; high-minded, gentle but firm in principle, literary, travelled, experienced, informed, pious, kindly, full of a mitis sapientia which in his talk he passed on to his lively and loving children. His mother was a gracious, pleasant, even jolly personality, delicate but brimming with social interest, daughter of Dr. Symonds of Clifton, a man of science, letters and art, and of many friends like the then Lord Lansdowne, Jowett, Tennyson, and Woolner, and sister of that fecund and fluent spirit, the author of the History of the Renaissance, with his wide sympathies and his genius for both stinging and steering the young.

" St. Loe " was never sent to school. In his nursery he had a nurse crammed with quotations ; then he browsed in the old library and grew up outside with the children of the village, and by and by went to a country- parson tutor. - - Presently he proceeded to Balliol, at that time under Jowett, his grandfather's and uncle's friend, and T. H. Green, his aunt's husband. The College was at the height of its force and fame, filled with brilliant and ambitious young men of family and talent, eager to anticipate their part in the world.

It was just before and after he entered Balliol I came to know him. He became my pupil and at once my friend. He was never a scholar. His passion for style was equalled by his impenetrability to spelling and grammar. But from his engaging enthusiasm, his voracious wide-ranging mind, his memory and his wit I learned much, and he was delightful company alike in lesson and in leisure. He made a hundred friends, but one in particular, Bernard, now Sir Bernard Mallet4?, a friend who then and ever after was a brother and more than a brother.

After many academic stumbles at early fences he got into the fairway and took a brilliant First in History. I went to hear his " viva" and was greatly relieved when the examiner by and by led him on to Euphuism in Shakespeare. Strange to say, that examiner, a country clergyman from Somerset, a friend of Freeman, has outlived his examinee and is still with us.

From Oxford he went to London and the Bar ana by and by married, his wife, a granddaughter of Nassau Senior, introducing him to yet further circles of law and literattire. But the Spectator was his fate. His entry into it is a fairy tale. His first four stripling articles were a miracle. In the realm of journalism he was the Fortunate Youth, the Fairy Prince, Whittington with the Spectator eat on his shoulder.

It was already an entity and an institution. Hutton -and Townsend were a notable pair. Under them it was unworldly, theological, metaphysical : Strachey, following Socrates and " Euphues " and Addison himself, brought its philosophy from the sky to the earth, from colleges to clubs and tea-tables. He made it more prosperous, more worldly even. Yet it retained its conscience and its soul. It did not go the way of so many journals. He refused to sell it to the Philistines. It never became the puppet of a millionaire.

It is sad that its Centenary, a year hence, should find' him no longer in control ; less sad perhaps for that reason,--' yet still sad, that he should not be there to see that day. But he lived to see it re-established and regaining, under -new management, its old sane and sound policy and -prosperity. In a hundred years to have had only 'five 'editors is a remarkable record, and all the four who belong now to its past have been men of singular mark.

Strachey, above all, had ' moved with the times: Soyez de votre siècle was his watchword. He affected, more than they knew, his day and generation.

" The world's mine oyster which I with sword will open," he said to himself as an Elizabethan young Man. But his sward was a pen.

His five great men, the Duke of Devonshire, Chamber- lain, Lord Cromer, Roosevelt and Hay, were men of action if some of them were men of letters too. And he himself was also a 'man of action. He became Sheriff of Surrey. He devised a system of registering reservists. He developed the Surrey Guides and the Surrey rides. In the War his house became a hospital with his wife as commandant, while he went to inspect the firing line and mobilized the American journalists in London.

Open, generous, with a genius for friendship both public and private, and a flair for good writers and writing, an incorrigible optimist, he enjoyed his career, often hugely. Rebuffs and sorrows, one above all, the loss of his eldest son on the threshold of life, were his, but he " could not rest from travel." Only the other day he came back from a fatiguing rush through Canada and the States. He lived while he lived : zest, gusto, élan vital, joie de vivre—style it in what tongue, by what term you will—was his dominant characteristic. And now : " Men must endure their going hence even as their coining hither." His father had been a church- man of the older quietistic Evangelical' settool.- own final- creed was that he had " faith in faith " and in the Mercy of God. To this ,his mourners and his friends, 'old and young, must to--daY resign 'aid' commend him.

HERBERT WARREIC

Previous page

Previous page