Chess

Special Ks

Raymond Keene

This week want to assess the play in the Karpov-Korchnoi world championship match and suggest several reasons for the latter's drastic defeat. In spite of Korchnoi's generally tough physical condition, his age (50) Finally appears to have caught up with him, and in view of Korchnoi's splendid successes at Rome, Lone Pine and Bad Kissingen earlier this year, Robert Byrne's comment is highly relevant: 'He seems to have aged ten years in just six months.'

Then there was Korchnoi's openings analysis, a responsibility shared with his team of supporters. In this department he was much inferior to the Russians, sticking to repetitive and lacklustre openings with White, while his excessive reliance on the suspect Open Lopez eventually caused his undoing, costing him two losses from his last three games with Black. Karpov's opening play, on the other hand, was vastly more varied and energetic. Indeed, throughout all phases of the games, he scarcely committed any serious errors (ex cept for 40 Nfl? in game 6 and 29 ... Be7? in game 13) and the overall accuracy of his play suggests that he would even be able to thrash Bobby Fischer, in the unlikely event that the American genius should emerge from his nine-year self-imposed exile. The world champion's outstanding achievements were games 9 and 18, which showed at its very best his sophisticated ability to launch powerful attacks from simplified positions.

A further factor contributing to Korchnoi's defeat was the enforced absence of his wife and son. It should not, however, be overlooked that they were just as absent at Baguio, where he put up much more of a fight, and during his subsequent Candidates' series wins against Petrosian and Polugaievsky. Indeed, the line often taken by Korchnoi's aides was that the situation of his family would spur him on to greater exertions. Now that his challenge has been beaten off for the second time it is only to be hoped that the Russians will at last relent and set these unfortunate people free.

Finally, the lack of disputes must have made Korchnoi feel uncomfortable. There was no shortage of contentious issues, such as his insults to Karpov, his use of gurus and reflecting glasses and his disappearances offstage during play, but the Russians refused to bite and took it all very calmly. In a revealing interview Karpov's press agent explained the quiet Soviet policy: 'We have a very clear outlook here, in comparison to Baguio. We are consciously striving to avoid anything controversial and any kind of disturbance that would distract from the match as a purely chess contest. Distractions and controversy only benefit the weaker player, and we firmly believe in Karpov's superior strength over the board.' In contrast, Korchnoi and his group seemed to be enjoying anything but a clear view, and rumours were rife of violent criss-cross dissent between Petra Leeuwerik, Didi (from the Ananda Marga), Korchnoi's whole band of dissident ex-Soviets and the all too rapidly dismissed Shamkovich.

It was, perhaps, as a result of this, that Korchnoi experienced total disaster: he is the first challenger since Bogoljubov in the 1930s who has twice failed in his bid to unseat the champion (then Alekhine), while he suffered additionally by losing the shortest world championship match for 60 years, since the aged Lasker went down in 14 games to Capablanca at Havana 1921.

If Korchnoi has one consolation it is the jewel of game 13, an absolute model of attacking play and one which will justly take its place in future anthologies of chess brilliancies.

International chess has suffered a great loss with the death of Dr Max Euwe, world champion 1935-37 and Fide president 1970-78. I shall be writing about him shortly.

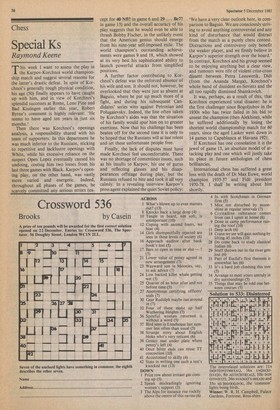

Previous page

Previous page