ARTS

Architecture

Lament for Coleshill

Alan Powers on the destruction 40 years ago of a classic English country house

Coleshill House is no more,' wrote John Burrow-Hill, conveying the news to the Secretary of the National Trust on 24 September 1952, the day after a fire had destroyed much of one of England's finest 17th-century houses. It is nearly 40 years since that unhappy day, when a spark from a blowtorch somehow managed to set the whole house ablaze during a painters' tea- break, and Coleshill deserves to be remem- bered.

English country houses are valued for many reasons, sentimental or snobbish, for their contents or decoration, but Coleshill's value was almost entirely architectural. Nothing happened there of any importance during the ownership of the Pleydell fami- ly, later married to the Earls of Radnor, who inherited from the Pratts in the 18th century, unless one is to include the Japanese tea ceremony carried out in the drawing-room in the 1930s by Tsuronoke Matsubayashi, a colleague of the potter Katherine Pleydell-Bouverie, one of two sisters who after the war arranged for the sale of Coleshill to Ernest Cook, a well- known 'anonymous benefactor' to the National Trust, to whom the house was intended to pass. Coleshill, in the part of Berkshire incor- porated in Oxfordshire in 1974, was built between 1650 and 1662 for Sir George Pratt by his cousin, the amateur architect Sir Roger Pratt. Coleshill represents a shadowy period of English architecture between Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren. The puritanism of its design may be taken to represent the Cromwellian era of its gestation, but the seeds were gathered during Roger Pratt's foreign studies in the period of the Civil War which took him to France, Italy, Flanders and Holland. He knew Inigo Jones, and accompanied him on a visit to Coleshill in 1651 when Jones was 78. In spite of further Jones connec- tions, it seems safe to attribute the design wholly to Pratt, whose genius was to syn- thesise his foreign influences and make something, in the words of Sir John Sum- merson, 'massive, serene, thoughtful, abso- lutely without affectation'.

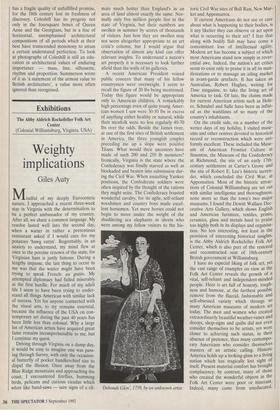

Coleshill introduced the 'double-pile' Plan, with central corridors on each floor, enabling the exterior of the house to be expressed as a volume uninterrupted by breaks or incidents. The way that this pure volume was enhanced by the careful spac- ing of simple architectural elements made Coleshill unique. The string course between the floors and the cornice at the eaves bind the house, and the hipped roof and substantial chimneys complete the Composition. What Pratt designed at Coleshill, but not at his other houses such as Kingston Lacy or Clarendon House in Piccadilly, was a distinctive spacing of the windows, with the centre three wider apart than the three grouped at the ends. Although this is dictated to some extent by the logic of the plan (there are massive cross-walls bearing the four chimney-stacks in the centre of the house), it is a visual device familiar from almost every Venetian facade, which Palladio developed into an art form.

How sadly ironic it was that James Lees- Milne, the Historic Buildings Adviser to the National Trust, learned of the destruc- tion of Coleshill while reading the Times on the Grand Canal. He wrote immediately to Robin Fedden at the Trust, urging that Coleshill, 'one of the best pieces of domes- tic architecture England ever produced', offered a good case for rebuilding. 'I am not one for rebuilding on the whole,' he explained, but Coleshill was 'the earliest English country-house to be designed as a classical entity. Other important houses contemporary with it, like Thorpe Hall and Raynham, were still Flemish in detail, or added to like Lamport, or even entirely Italian reproductions like the Queen's House, or still Jacobean like the majority of the pre-Wren houses.' These matters would have been on his mind, since he had recently completed the book The Age of Inigo Jones which on publication in 1953 compared Coleshill to 'a sonnet by Milton, wherein are compressed infinite subtleties of meaning'.

Although Lees-Milne galvanised the Council of the National Trust to resolve that 'in view of the importance of Coleshill they would recommend the rebuilding of the house if funds permitted', the matter was hardly in their hands. Techniques for rescuing damaged buildings were less sophisticated than now. The house was not yet the Trust's property and the expert opinion canvassed by Burrow-Hill as Ernest Cook's agent denied the possibility of saving the walls and chimneys. These were demolished in February 1953, in spite of a letter to the Times from Lees-Milne, John Betjeman, Lord Esher and the archi- tects Albert Richardson, H.S. Goodhart- Rendel and Marshall. Sisson urging the use of the insurance money on rebuilding.

The classicism of the mid-17th century Coleshill House: an education in enduring architectural values has a fragile quality of unfulfilled promise, for the 18th century lost its freshness of discovery. Coleshill has its progeny not only in the foursquare boxes of Queen Anne and the Georgians, but in a line of horizontal, unemphasised architectural compositions of all periods which at their best have transcended monotony to attain a certain understated perfection. To look at photographs of Coleshill is still an edu- cation in architectural values of enduring importance — mass, line, silhouette, rhythm and proportion. Summerson wrote of it as 'a statement of the utmost value to British architecture', a value more often ignored than recognised.

Previous page

Previous page