STILL JUST FADING AWAY

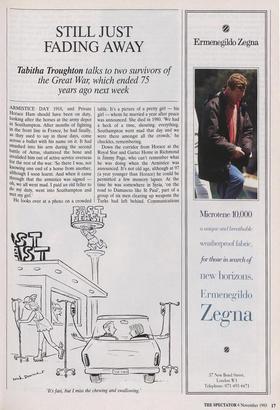

ARMISTICE DAY 1918, and Private Horace Ham should have been on duty, looking after the horses at the army depot In Southampton. After months of fighting In the front line in France, he had finally, as they used to say in those days, come across a bullet with his name on it. It had smashed into his arm during the second battle of Arras, shattered the bone and invalided him out of active service overseas for the rest of the war. 'So there I was, not knowing one end of a horse from another, although I soon learnt. And when it came through that the armistice was signed oh, we all went mad. I paid an old feller to do my duty, went into Southampton and met my girl.' He looks over at a photo on a crowded table. It's a picture of a pretty girl — his girl — whom he married a year after peace was announced. She died in 1980. 'We had a heck of a time, shouting, everything. Southampton went mad that day and we were there amongst all the crowds,' he chuckles, remembering.

Down the corridor from Horace at the Royal Star and Garter Home in Richmond is Jimmy Page, who can't remember what he was doing when the Armistice was announced. It's not old age, although at 97 (a year younger than Horace) he could be permitted a few memory lapses. At the time he was somewhere in Syria, 'on the road to Damascus like St Paul', part of a group of six men clearing up weapons the Turks had left behind. Communications

it's fast, but I miss the chewing and swallowing.' were bad and they didn't know it was all over until they got to Tel Aviv. Even then, celebrations were muted.

'Armistice Day,' Jimmy says witheringly. 'It leaves me cold. I got neither pleasure nor profit out of the war. It robbed me of five years of youth and retarded my hopes of doing something with my life. The only thing Armistice Day does is irritate some of the chips on my shoulder.' He fixes me with blue eyes somewhat blurred by too much red wine at lunch-time the day before. 'Well, do you have the list of questions you want me to answer?' I fumble in my bag. 'Being interviewed wouldn't be so painful if I was reported accurately,' he adds quellingly. I hastily assure him that I'll do my best. An alarming high-pitched wheez- ing follows; I look nervously around for a glass of water before I realise what it is: Jimmy Page is chuckling too.

They couldn't be more different, Horace and Jimmy. The only things they have in common are their extreme age and the way in which, as they talk, images of the young men they once were flicker eerily behind the networks of fine wrinkles, like ghosts. Horace is over six foot tall ('the tallest man in my battalion, and even then I was up to my waist in water in the trenches'), still broad-shouldered, wearing, incongruously, a baseball hat to keep the light out of his eyes. 'They went a year ago — if it wasn't for that and my bad knee, I'd be fine.'

Jimmy is slight, puckish, charming, with a short white beard which bristles challeng- ingly whenever he says anything controver- sial, which is quite often. 'Look at this,' he says, showing me a letter from No. 10 Downing Street, enclosing a photo of when Jimmy met Margaret Thatcher. 'How won- derful,' I say, overlooking the four inexcus- able spelling mistakes so as not to shatter his illusions. 'There are four spelling mis- takes,' he says with outrage. 'I wrote to Denis Thatcher. At the back of my mind was the idea that something better should have been available to his wife, even though she is a bitch.' He looks at me with delight and cackles again.

There's a natural temptation to be undu- ly deferential with Great War survivors; they don't want it and they don't need it. Once you get over that misapprehension, it's easy to talk about anything with Horace and Jimmy — their jobs, their families, their hobbies. And, of course, the war. Both, it turns out, have been interviewed about the war so often they could do it in their sleep, suitable candidates for the media becoming thinner on the ground in recent years. 'I don't mind,' says Horace reassuringly. 'It helps pass the time, to be honest with you.'

The stories lose nothing by repetition. Jimmy joined up out of pride: 'I couldn't walk around hiding behind the skirts of women.' Horace joined up with four friends after a recruitment officer had called at the country house where he was working as a footman. 'I was one of those "Ooh, there's a war on, we'll join the army" , ' he says, shaking his head. 'And it was fun, at first, when we were training in England.'

It stopped being fun rather quickly. As they talk, you can almost see it happening. Jimmy, sweltering in Gallipoli, pouring liq- uid bully-beef out of cans, getting dysentery and jaundice, losing three-and-a-half stone before being taken to Alexandria 'to die'. Horace at the Somme, seeing two of the friends he enlisted with die, going over the top with the 800-strong battalion and being one of the 100 who made it back. Jimmy being overcome by the heat and lack of water; Horace being alternately frozen and flooded out in the trenches.

Jimmy, possibly because he's not feeling well, possibly because it's still painful, probably because — fair enough — he just doesn't feel like it, is shorter on details than Horace. Horace produces stories about the war until he sounds like oral his- tory personified. They were scared all the time. Horace had so many near misses that he still describes them with a kind of dis- believing awe: 'There was the day when the corporal was shot through the head, stand-

ing as close to me as I am to you. And the time when machine-gun fire smashed both the panniers on my back to smithereens — I wasn't even touched.'

But it's the sheer, grinding misery which comes out most vividly: months spent waterlogged and hungry, chipping mud off the bread rations, sleeping — or trying to sleep — in cubby-holes scraped out of the side of the trenches, watching rifles freez- ing to the side of the trench in the winter of 1917. `Nobody knows what we had to go through. Nobody, unless they were there, could possibly know.' Jimmy agrees: 'Most people don't even know where Anzac Cove or Gallipoli arc. But they should. It's important that people know.' He sounds, unsurprisingly, bitter.

It still must be odd, I say to Horace, talk- ing about the war so much. There have, after all, been decades in between when both men lived perfectly ordinary lives. Horace went on to run his own pub, Jimmy went back to electrical engineering. `You must have seen some startling changes,' I say, meaning politics. Yes, they agree, rem- iniscing about when a bottle of whisky cost 3s 6d, when Jimmy was earning £350 a year — 'and that was a good salary'.

But, looking back, I ask both of them, 'What do you think have been the real changes? What do you think of the country now?' Both instantly say that it's gone downhill. `I'm a Conservative, but Mar- garet Thatcher's getting as bad as Ted Heath,' says Jimmy. What about John Major? 'I still haven't formed an opinion of him,' says Jimmy grandly. Horace, a Con- servative as well, disagrees about Major — 'he's a good man' — but is generally pes- simistic. 'They've got everything mixed up. He's got a lot of hard work in front of him.'

Neither fought in the second world war — Horace was just too old, Jimmy's wife persuaded him to go into the Admiralty. But both, amazingly, say that they would have done. 'The war was worth it,' says Horace firmly. `Now it's all gone haywire again, though. Don't know what to make of it, really.' His voice, for the first time, tails off. He's getting tired. Jimmy reacts more strongly. 'When I got back, I shut up like a clam. There was no point in talking about it, about medals. Everybody had them. There were people shaking tins for alms in the street. 'Now,' he says imperiously 'I think you've got enough.'

I turn the tape-recorder off. Jimmy smiles, relaxes, and asks me if I would write to him. Horace, next door, is equally cour- teous. 'I do hope I haven't bored you,' he keeps saying.

Outside the Star and Garter it feels like a different world. Inside are men of all gen- erations who have fought, suffered, seen things that most people, myself included, couldn't begin to imagine going through. 'I'd have just run away,' I had said to both of them, meaning it. The thought, a quintessentially modern one, had obviously never occurred to either of them.

Previous page

Previous page