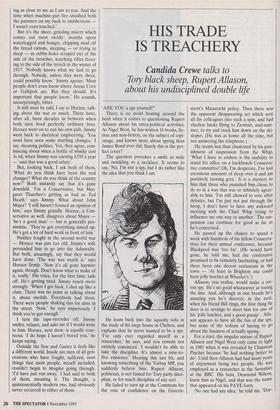

HIS TRADE IS TREACHERY

Candida Crewe talks to

Tory black sheep, Rupert Allason, about his undisciplined double life

`ARE YOU a spy yourself?'

There is no point beating around the bush when it comes to questioning Rupert Allason about his extra-political activities. As Nigel West, he has written 16 books, fic- tion and non-fiction, on the subject of espi- onage, and knows more about spying than James Bond ever did. Surely this is the per- fect cover?

The question provokes a smile as wide and twinkling as a necklace. It seems to say, No, I'm not a spy, but I do rather like the idea that you think I am.'

He leans back into the squashy sofa in the study of his large house in Chelsea, and explains that he never wanted to be a spy. 'I've only ever regarded myself as a researcher,' he says, and you remain not entirely convinced. 'I wouldn't be able to take the discipline. It's almost a nine-to- five existence.' Hearing this last bit, and knowing something of the Torbay MP, you suddenly believe him. Rupert Allason, politician, is not famed for Tory party disci- pline, or for much discipline of any sort.

He failed to turn up at the Commons for the vote of confidence on the Govern- ment's Maastricht policy. Then there was the apparent disappearing act which sent all his colleagues into such a spin, and had clueless hacks flying to Zermatt, mid-sum- mer, to try and track him down on the ski- slopes. (He was at home all the time, but not answering the telephone.)

He seems less than chastened by his pun- ishment of suspension from the Whip. 'What I have to endure is the inability to stand for office on a backbench Conserva- tive committee! Oh, I'm desperate, I've lost enormous amounts of sleep over it and am positively turning grey.' It is a mystery to him that those who punished him chose to do so in a way that was so infinitely agree- able to him. 'I'm still allowed to vote after debates, but I'm just not put through the hoop, I don't have to have any awkward meeting with the Chief Whip trying to influence me one way or another.' The sus- pension can continue for good as far as he's concerned.

He passed up the chance to spend a week with hundreds of his fellow Conserva- tives for their annual conference, because Blackpool was 'too far'. (He would have gone, he told me, had the conference promised to be remotely fascinating, or had there been one decent restaurant in the town — 'At least in Brighton one could have jolly lunches at Wheeler's.') Allason, you realise, would make a rot- ten spy. He's no good whatsoever at toeing the line. And, although in one breath he's assuring you he's discreet, in the next, when his friend Bill rings, the first thing he does is to arrange to meet him for one of his 'jolly lunches, and a good gossip'. Alla- son appears to have all the fun of the spy, but none of the tedium of having to go about the business of actually spying. For a start, the singular nature of Rupert Allason and Nigel West only came to light in 1981 when it was revealed by Chapman Pincher because 'he had nothing better to do'. Until then Allason had had many years of enjoyment being two people. He was employed as a researcher in the Seventies at the BBC. His boss, Desmond Wilcox, knew him as Nigel, and that was the name that appeared on his PAYE form. 'No one had any idea,' he told me. `Dur-

ing the 1979 election campaign, I just said I was taking two weeks' leave. On one occa- sion I was at the annual general meeting of the Kettering Conservative Association, and the deputy chairman said, "I was watching telly last night, and there was this man, I swear he was your double. It's quite uncanny. He even had some of your man- nerisms." So I told him it was me. "It couldn't have been you," he said, "he was an expert, really knew what he was talking about."'

West gets to meet more spies than any Spy ever would. His brother, Julian, says he's not a good life insurance candidate. The places he hangs out,' he shudders, 'and with a lot of dodgy characters. No one would be surprised if he completely disap- peared one day.' While Rupert Allason is a member of White's, Nigel West is a mem- ber of the Special Forces Club, 'the least sinister member of which is an ex-SAS man,' says Julian. 'It's where all the spooks hang out. They meet in some semi-under- ground fortress under some railway bridge.' 'When you talk to a spy like Blunt, for example,' Rupert — or Nigel — told me, You find that all they really want is a gin and tonic, and a really good gossip. They Can tell me the funny stories they could never confide to a friend for fear of betray- al, or to another spy because spending too much time in the company of fellow con- spirators might draw attention. So they'd be itching to tell me things.'

Perhaps it is his knowledge of their trade Which also prompts them to do so. It derived initially from an interest in history, and was fuelled when, still at university, Allason worked as a researcher for two authors on espionage, Then at 'the forma- tive moment of my intellectual develop- ment', all that he was brought up to believe, particularly in relation to the sec- ond world war, turned out to be incom- plete. 'Suddenly we started to get a lot of revelations, about Bletchley Park, for example, and the conventional biographies of the likes of Eisenhower turned out to be n.onsense. The late Sixties and early Seven- ties was a period of disclosure, and I found an opportunity to make a difference.' It was his long-term expertise, knowing all the references, the jargon and personali- ties, as well as sticking to his promises not to reveal the spies' true identities, which enabled them to talk.

It was a huge relief for them to talk to i me; t was like therapy.'

Allason doesn't strike one as one of the World's most natural therapists. He has that easy, confident manner which perhaps comes from a mother 'who fancies herself as a society hostess'; a deeply conventional and secure background — 'I had the same 11. anny for sixteen years and have only lived

three houses in my entire life'; a keen

intelligence (even though at Downside they s.

aid he was too stupid to join the army — how stupid must they have thought him?); and, finally, wealth (huge by all accounts, and only negligibly dented by Lloyd's, so he told me. The Porsche still glitters in the drive outside).

Unlike many who felt the end of the Cold War meant the death of spies and their literary spin-offs, West believes that 'now more than ever' espionage is crucial. 'Especially if we're going to dismantle the armed forces, it's important to have a trip- wire to alert us to potential danger. The Falklands war, deemed to have been a suc- cess, was in reality a grotesque failure of intelligence, and should never have hap- pened. If we'd had a good source in Bagh- dad, we'd have deployed troops in Kuwait and deterred Saddam from invading. Good intelligence prevents bloodshed. In the past, we just had to know about Moscow. Now there are four nuclear powers in the old Eastern bloc, and we don't know who's in control. And I haven't touched on Islam- ic fundamentalism, for example; China; Indonesia.'

Allason is deemed to cut a dashing fig- ure. Sartorially speaking, I expect some could do with a little less of the rather too Seventies-style cut of trouser, but he has a good-looking face and nice shoes. And blonde females seem to flock round him, according to his brother, though he mar- ried (in 1979) dark-haired, race-horse-own- ing Nikki van Moppes, whom he refers to as 'the boss'. They have two children and are not separated, despite rumours to the contrary.

'We wanted to go on living the way we always lived. I suppose we aren't a conven- tional couple.' Does he take advantage of their long periods apart, often in separate countries? 'I don't have other girlfriends — genuinely.' He answered my cheeky ques- tion immediately, and with a frankness which — serve me right — quite disarmed me. As I paused with surprise, he added, of his own accord, 'I haven't slept with anoth- er girl since I was married.' He was so straightforward about it, I couldn't not have believed him.

Then the telephone rang for the umpteenth time. It was yet another friend after some advice. He listened for a long while to the caller's problem. 'Never trust a politician with anything serious,' he said eventually. A deeply held sentiment by the espi- onage expert? or the MP's little joke? As with most aspects of the Allason/West dou- ble act, as the Tory whips, his constituents and many others have found, it is simply impossible to know the truth.

'Sexy guy, into travel. . nothing about being a damn' owl.'

Previous page

Previous page