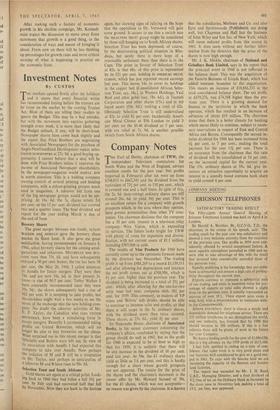

Growing Pains in the U.S. Economy

By RICHARD BAILEY TN his message to Congress on the Economic 'Growth Programme Mr. Kennedy said the performance of the American economy over the past seven years had not been good enough and that he proposed to do something about it. In the United States, according to Mr. Kennedy, the rate of growth from the high point reached in the second quarter of 1953 up to 'the anaemic recovery seven years later' was around 2.5 per cent. a year. The President's message went on to spell this out in some detail. Last year whereas the economy could have produced 535 billion dollars' worth of goods and services, only 503 billion dollars' worth were forthcoming. Mr. Kennedy claimed that this meant that over one and a half million unemployed could have had jobs, 20 billion dollars more of personal income could have been earned, and corporate profits could have been 5 billion dollars higher. And all this, he argued, 'could have been accomp- lished with readily available manpower, materials and machines—without straining productive capacity and without igniting inflation.'

What has been the reaction to this statement by informed opinion in the United States? The difference of opinion at the top between the 'growth at any price' and the 'tackle the hard spots first' schools is reflected in reports coming from two leading research institutes. In Looking Ahead, the journal of the National Planning Association,* Gerhard Colm, NPA's chief economist, points out that even the relatively modest growth rate of the 1950s was boosted by exceptional factors. The chief of these was rearmament spending after the Korean War, and extra money for school, housing and highway programmes. Those who recognise this fact are apt to take a pessimistic view of the prospects for the 1960s. The NPA, however, after due con- sideration, comes out more optimistically than the Administration and argues for a 4 to 4.5 per cent. rate of growth. This is based on the belief that defence spending is likely to increase and that the Government will be voting more money for schools, roads, health, farm support and welfare programmes generally.

Dr. Colm agrees that the immediate prob- lems are both cyclical and structural—those to do with the ups and downs of business activity, and those due to more permanent changes in the way industry is run. Given reasonable luck the Government should be able to spend its way out of the cyclical problem and get the motor-car workers of Detroit, for example, busy again. But the coalminers of West Virginia are in an * 'The Economic Outlook for 1961'—LooKING AHEAD, December, 1960. industry that no amount of general federal spending will get back into full operation. Dr. Colm believes that a level of only 4 per cent. unemployment in 1963 is within the realms of possibility. This assumes a rate of growth of 7.5 per cent., which is double that which Mr. Ken- nedy and Professor Heller, chairman of the Com- mittee of Economic Advisors, are committed to. But this sort of result cannot be achieved by higher government spending alone. To be effec- tive private spending will have to be stepped up and industry must start investing more, not only in modernisation, but in extending its plant and continuing its search for new products. To do this in an era of higher business taxation and a profits squeeze managements will have to raise productivity. Given these conditions expansion in the public sector 'will induce a vigorous expansion in the private sector of the economy.'

Another research organisation, the Committee for Economic Development, in a pamphlet entitled Growth and Taxes,t examines the con- ditions for economic growth in a different context. The CED states that the bulk of any acceleration in growth rates must come from the private sector of industry, where 90 per cent. of production takes place. The Federal Govern- ment exerts its biggest influence on the private sector through taxation, the yield of which, to- gether with social security contributions and other fixed payments, runs into about 100 billion dollars a year. The CED pamphlet defines the prerequisites for sustained growth as 'adequate savings and investment in areas that improve efficiency and increase productive capacity,' and urges the revision of the tax system in a way that will boost risk-taking and initiative.

CED draws up, a list of eight specific changes in the federal tax structure that it claims will give better growth prospects. These include some which have a familiar ring about them, such as the lowering of income tax on higher incomes, more liberal depreciation allowances, and the auditing of business expense accounts. But another is the demand for better tax enforcement and administration. CED regards its tax reform recommendations as 'a single package in which the separate items complement and reinforce each other.'

The whole scheme, it is claimed, would alter the present aggregate tax yield little, if at all, but would shift the whole emphasis to give greater incentives to individuals and companies to dis- play initiative and to save and invest. These are clearly the sort of changes needed in the Ameri- can economic system at the present time.

t. GROWTH AND TAXES. CED, February, 1961.

After making such a feature of economic growth in his election campaign, Mr. Kennedy must expect the discussion to move away from statements that growth is a good thing, to the consideration of ways and means of bringing it about. From now on there will be less thinking up percentages for growth rates and more critical scrutiny of what is happening in practice on the economic front.

Previous page

Previous page