NOVELS

Only Connect

The Ice Saints. By Frank Tuohy. (Macmillan, 21s.)

THE first chapter of Frank Tuohy's third novel, The Ice Saints, which throws at the reader a cast of interrelated characters conversing in de- tached dialogue, might have been designed to discourage. Anyone who perseveres through this Will be rewarded with a most impressive novel. Mr. Tuohy writes with E. M. Forster's sensiti- vity to the nuances of personal relationships. Indeed, the only surprising thing about Rose, his Principal character, is that her acute sensitivity Should have allowed her to reach the book's oPening without earlier emotional disaster. But it is an acceptable suggestion that Poland in 1960 should be the catalyst for this.

Rose goes to Poland to carry the news of a legacy : her fifteen-year-old nephew, son of her sister and a Polish Communist, has been left money by an aunt. The possibility of the boy's escape is thus raised, but also the possibility of disaster for the whole family, because to fail to declare foreign currency could be fatal. To point the choice the story is set against the appalling drabness and poverty of life in a Polish pro- vincial university town. Things are not as bad as they were in Stalin's day, Rose is continually told. And in one sense it is easy to understand how there was more fear and oppression : 'the Confiscation of their [her sister's] savings, the Pollee terror, the lack of food and the loss of their second child, were a progression that was Pointing in only one direction, towards their anal destruction.' But in another sense it is im- possible to believe that anything could be worse than the negative hopelessness of 1960. If the terror had gone, so had its stimulus.

'God must come and blast the inhabitants of Heauchamp Place, and frizzle up those on the Pavements outside Harrods. Only then, surely, Could He bring about a balance of the world's Pain,' Rose feels. This background of pain is tile essence of the story, and, like Rose, we are hshamed by it. For, nasty as it may be for Tuohy's "les, and much as we may suspect that they are histrionic victims of a national death wish, they are concerned with realities. By comparison, °,11r own concerns are reduced to those of Children in a nursery of expensive toys.

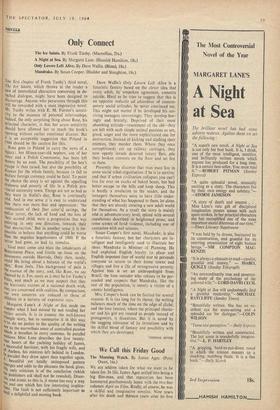

' Margaret Lane's A Night at Sea made me Wonder what I had missed by not reading her earlier novels. It is in essence the well-known triangle story, but to summarise it in this way 13 to do no justice to the quality of the writing noI to the marvellous sense of controlled passion Which it breathes in every sentence. In parallel feetions Miss Lane describes the first twenty- Our hours of the yachting holiday of James, 4 successful barrister, with his fragile wife, and Anthea, his mistress left behind in London. hl Parallel they draw apart then together again. beautiful yet totally unimposed pattern nerges and adds to the pleasure the book gives. tIllY only criticism is of the conclusion (which Publishers ask shall not be revealed). Dram- ue and ironic as this is, it seems too easy a way tlat and one which has few interesting implica- ls. The fault is not sufficiently important to Doil a delightful and moving book. Dave Wallis's Only Lovers Left Alive is a futuristic fantasy based on the clever idea that every adult, by unspoken agreement, commits suicide. Hard as he tries to suggest that this is an apposite reductio ad absurdum of contem- porary social attitudes, he never convinced me. This might not matter if he developed his sur- viving teenagers interestingly. They develop bor- ingly and brutally. Deprived of their most absorbing attitude—resentment of the old—they are left with such simple animal passions as sex, greed, anger and the more sophisticated one for destruction. Instead of kicking and slashing their enemies, they murder them. Where they once surreptitiously cut up railway carriages, they now openly invade deserted luxury flats, pile their broken contents on the floor and set fire to them.

Presently they discover that man must live in some social tribal organisation if he is to survive; and that if urban civilisation collapses you can't live for ever on stocks of baked beans, but had better escape to the hills and keep sheep. This is hardly a revelation to the reader, and the teenagers themselves seem to have little under- standing of what has happened to them, let alone, that they are already creating a new adult world for themselves. As a result the story is mainly told at adventure-story level, spiced with several copulations described in heightened prose, and some scenes of lurid violence, including one of castration with nail scissors.

Susan Cooper's first novel, Mandrake, is also a futuristic fantasy, but her characters are in- - telligent and intelligently used to illustrate her ideas. Mandrake is Minister of Planning. He had exploited English loyalty to place and English impotent fear of world war to persuade everyone to return to their home towns and villages and live a life of retrogressive poverty. Against him is set an anthropologist from Brazil, the lone outsider who refuses to be per- suaded and suspects that Mandrake, like the rest of the population, is merely a victim of a cosmic Intelligence.

Mrs. Cooper's book can be faulted for several reasons. It is too long for its theme, the writing balances much of the time on the edge of clich6, and the love interest, where the principal charac- ter and his girl are treated as people instead of protagonists, is disastrous. But it is saved by the nagging relevance of its inventions and by the skilful blend of fantasy and possibility with which they are developed.

THOMAS HINDE

Previous page

Previous page