Magic moments

Martin Gayford talks to the painter Euan Uglow about his work Looking at the world .. . ' I start to say, but Euan Uglow finishes my sentence for me, `... is magic.' And when his work really works, magic is exactly what you get from it. In one of his paintings on view at Browse and Darby, Cork Street, London, W1 (until 31 May), a pear sits on a grey sur- face. Behind is a wall of slightly greenish blue. The position of pear — its surface faceted into planes of subtly darker or lighter yellow — is plotted on the little rect- angle of canvas as if in the sights of a rifle. It is bang on the middle, looking from right to left, but its centre of gravity is in the lower half, from top to bottom. As pears tend to be, it is not itself quite symmetrical, but shaped instead like a fat inverted comma, With its stalk pointing off to the right. That's all there is. It couldn't be simpler. But the colours are so limpidly just right, the proportions of the composition so lucidly harmonious, that you could look at it for hours — indeed, for a lifetime if you were lucky enough to own that Uglow. Conjuring poetry like this from precision, mystery from mathematical exactitude, abstract yet figurative, is a kind of magic in art. It is no wonder that it sometimes takes Uglow a long time to bring it off. His pictures may take a number of years — 'The Wave', in this show, is dated 1991- 97. Since many of his paintings depict not fruit but naked girls, this adds an extra dimension of difficulty to the enterprise, both for the model and the artist. The Woman who posed for 'The Wave' was a student when she started, Uglow remem- bers, 'now she's a lawyer, so smart I have to telephone her secretary to get in touch'. Modelling for Uglow is evidently quite an obligation. 'It's a terrible commitment, I'm sure. I feel sorry for them, but I can't go any faster. Of course, I could splodge off something in three quarters of an hour, but it wouldn't mean anything to me.'

His small output, and the rarity of his exhibitions — the last in London was in 1991 — explain why his work is not better known. Uglow, however, is one of the most respected of those painters in London who continue to make paintings about the world around them. 'School' is the wrong word for them since they are all completely dif- ferent. But in very diverse ways, most of them have worked out elaborate strategies for making fresh, uncliched images of their subjects.

In Uglow's case, that means going to great lengths to make sure that every time he sits down to paint he sees absolutely the same thing. Scattered round his house in South London — basically a series of stu- dio spaces with rather austere arrange- ments fitted in between them — one sees the settings for various paintings. In front of the artist's chair, hangs a plumbline, with another line crossing it. 'If you're painting one image over a period, it seems to me important that you should have your eye in the same place every time,' he says. 'The vertical and horizontal lines there are for me to get my eye in the right place. So if you were to sit in that chair, you'd find the plumbline went along the central line there.' For one picture, he explains, 'unless the centre line was through 'her bosom, one might as well not have painted. Everything would be wrong, and one would lose the whole point of the picture.'

Around the low couch where the model lies, there are myriad chalk marks; above, a light box hidden in a cardboard box. The whole set-up looks like a piece of laborato- ry equipment for some home-made experi- ment, and in a way it is. For 'Nude, From Twelve Regular Positions From the Eye' (1967), he had the model stand with her neck held between two pegs, while he stepped up and down a specially construct- ed ladder to observe from the 12 positions, each an exact six inches apart. 'I'm not interested in producing pictures,' Uglow says. 'I'm interested in personal research, even if it's a disaster.'

The research is into two things — the form he actually sees, and the various har- monious ways a rectangular painting can be divided. The first might seem obsessively literal-minded, the second rather abstract. But, then, good figurative painting has to have a formal harmony which you could call abstract (while, conversely, good abstract art often turns to echo something in the world).

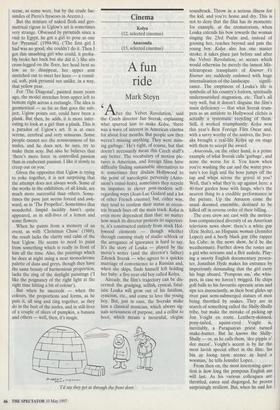

The combination of crystalline geometry and tender accuracy is one that crops up from time to time in art. It is there, for example, in Piero della Francesca, an artist Uglow plainly reveres. (Although he sel- dom goes to the cinema, he recently went to see The English Patient, and was sick- ened and horrified, not by the torture 'Pyramid', 1994-96, by Euan Uglow, on show at Browse & Darby scene, as some were, but by the crude fac- similes of Piero's frescoes in Arezzo.) But the mixture of naked flesh and geo- metrical rigour in Uglow's art is sometimes very strange. Obsessed by pyramids since a visit to Egypt, he got a girl to pose as one for 'Pyramid' (1994-96). (`The first girl I had was no good, she couldn't do it. Then I got this smashing girl who could; it proba- bly broke her back but she did it.') She sits cross-legged on the floor, her head bent so low as to disappear, her upper arm stretched out to meet her knee — a round- ed, soft, pink pyramid not unlike, in a way, that yellow pear.

For 'The Diagonal', painted many years ago, the model stretches from upper left to bottom right across a rectangle. The idea is geometrical — as far as that goes the sub- ject, Uglow points out, could have been a plank. But then, he adds, it is more inter- esting to look at a girl than a plank. This is a paradox of Uglow's art. It is at once serene, cerebral and very sensuous. Some people cannot see the sensuousness of his nudes, and he does not, he says, try to make them sexy. But also he believes that 'there's more force in controlled passion than in exuberant passion. I like it slowly to creep out on you.'

Given the opposites that Uglow is trying to yoke together, it is not surprising that the attempt does not always work. Some of the works in the exhibition, of all kinds, are much more successful than others. Some- times the pose just seems forced and awk- ward, as in 'The Propeller'. Sometimes that wonderful limpid lucidity hasn't quite appeared, as in still-lives of a lemon and some flowers.

When he paints from a memory of an event, as with 'Christmas Chase' (1988), the result lacks the clarity and calm of the best Uglow. He seems to need to paint from something which is really in front of him all the time. Also, the paintings which he does at night using a near monochrome palette of duns and greys, though they have the same beauty of harmonious proportion, lacks the zing of the daylight paintings (`I like the poignancy of the right light at the right time hitting a bit of colour').

But when he succeeds — when the colours, the proportions and forms, as he puts it, all sing and ring together, as they do in the best of the nudes, and in still-lives of a couple of slices of pumpkin, a banana and others — well, then, it's magic.

Previous page

Previous page