War and jewellery

Romancing the stone

Carol Woolton

YOU might not think it very important to be a jeweller during a war; hut it's at turbulent times like these that precious stones, necklaces, brooches, tiaras become more than mere accessories. They once again take on their historical role as the perfect way to encapsulate and transfer wealth. Simon Hefter asked recently, 'Just how are we going to pay for this war?' I wonder if he knows that for centuries wars have been financed by the sale of crown jewels, and that rare gemstones have paid for revolutions. Faberge swore that his business had never been better than in the early days of the Russian Revolution. The same applies today. Stephen Webster, one of Britain's leading young jewellers, has found his turnover in the United States has grown by 200 per cent since 11 September.

'Jewellery has never been just for adornment,' agrees the academic Diana Scansbrick. 'Ifs used for political purposes and as a financial asset.' Many spectacular dia monds have been put out to pasture, like old war horses, in museums around the world after years of active service on the war front. The 55.23 carat. pear-shaped yellow Sancy diamond, now in the Louvre. was originally pledged in 1589 by Nicholas de Sancy to Henry III of France to increase troops in his campaign against the Protestants. Bought in 1604 by James I, it was sold again by Henrietta Maria who was dispatched to Antwerp by Charles I to raise funds to purchase arms for the Royalists. In the 17th century the diamond crossed the Channel and passed into the hands of Cardinal Mazarin, the powerful French first minister, who bequeathed his collection of diamonds to the Crown. The Sancy was flogged again to support the army during the French Revolution.

Here, in the 21st century. the rebels in the Congo and Sierra Leone rely on the sale of 'conflict' diamonds to finance their battles, while $300 million worth of stones are extracted every year from the river beds of Angola to buy barrel-loads of kalashnikovs. And if our war against terrorism outlasts the contents of the Exchequer, then we can at least reassure ourselves that the crown jewels in the Tower of London are more valuable than any that bin Laden possesses.

Armies historically have ridden to victory wearing uniforms paid for with jewellery. Remember Scarlett O'Hara in Gone With the Wind tossing away her gold wedding ring to be used for the Southern cause? The Prussian royal family appealed to their citizens to donate gold in their war effort to achieve liberation from Napoleon. In return, each donor received a piece of iron jewellery engraved with the inscription 'Gold gab ich fur Eisen'. Mussolini, too, during the second world war appealed to every Italian mama to put down her pasta, remove her jewellery and offer it to the war fund.

Jewels are also the ideal way to hide and carry wealth in dangerous times. 'The demand for gold and jewellery is higher in countries with less stable regimes because of its transportability,' says John Payne of Baring Asset Management. If, just across the border, a local currency has little value, it makes sense to invest in gold, which has an international price and is measured by weight. Stones always have a store of value, as does a well-designed and signed piece of jewellery.

This excellent form of portable capital has been the source of survival for exiled citizens and fleeing émigrés. Henrietta Maria would have starved hut for the sale of her jewellery during her exile in Paris, and the Jews escaping from Europe arrived in Britain with diamonds sewn into the linings of their coats. 'I call it flight-money,' says Raymond Sancroft-Baker of Christie's. 'Leading families have always fled, taking pieces of jewellery with them.' We know it's what the doomed Russian royal family had planned, because precious stones, which they'd sewn into their underclothes, were found shattered by the gunfire.

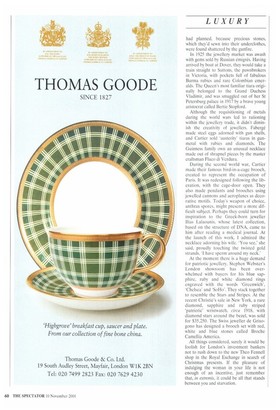

In 1925 the jewellery market was awash with gems sold by Russian émigrés. Having arrived by boat at Dover, they would take a train straight to Suttons, the pawnbrokers in Victoria, with pockets full of fabulous Burma rubies and rare Colombian emeralds. The Queen's most familiar tiara originally belonged to the Grand Duchess Vladimir, and was smuggled out of her St Petersburg palace in 1917 by a brave young aristocrat called Bertie Stopford.

Although the requisitioning of metals during the world wars led to rationing within the jewellery trade, it didn't diminish the creativity of jewellers. Faberge made steel eggs adorned with gun shells, and Cartier sold 'austerity' tiaras in gunmetal with rubies and diamonds. The Guinness family own an unusual necklace made out of shrapnel pieces by the master craftsman Fluco di Verdura.

During the second world war, Cartier made their famous bird-in-a-cage brooch, created to represent the occupation of Paris. It was redesigned following the liberation, with the cage-door open. They also made pendants and brooches using jewelled cannons and aeroplanes as decorative motifs. Today's weapon of choice, anthrax spores, might present a more difficult subject. Perhaps they could turn for inspiration to the Greek-born jeweller Ilias Lalaounis, whose latest collection, based on the structure of DNA, came to him after reading a medical journal. At the launch of this work, I admired the necklace adorning his wife. 'You see.' she said, proudly touching the twisted gold strands, 'I have sperm around my neck.'

At the moment there is a huge demand for patriotic jewellery. Stephen Webster's London showroom has been overwhelmed with buyers for his blue sapphire, ruby and white diamond rings engraved with the words 'Greenwich', 'Chelsea' and 'SoHo'. They stack together to resemble the Stars and Stripes. At the recent Christie's sale in New York, a rare diamond, sapphire and ruby striped 'patriotic' wristwatch, circa 1918, with diamond stars around the bezel, was sold for $35,250. The Swiss jeweller de Grisogono has designed a brooch set with red, white and blue stones called Broche Camellia America.

All things considered, surely it would be foolish for London's investment bankers not to rush down to the new Theo Fennell shop in the Royal Exchange in search of Christmas presents. If the pleasure of indulging the woman in your life is not enough of an incentive, just remember that, in extremis, it could be all that stands between you and starvation.

Previous page

Previous page