The Royal Family (Theatre Royal, Haymarket)

The Merchant of Venice (The Pit)

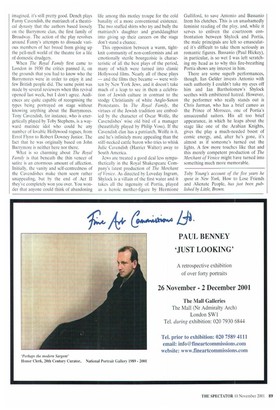

Won over

Toby Young

When I first learnt that Peter Hall was directing a play called The Royal Family at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, I thought it must be some modern satire about the Windsors, particularly when I discovered Judi Dench was in the cast. Clearly, the actress who gave such memorable performances as Victoria in Mrs Brown and Elizabeth I in Shakespeare in Love was going to play the Queen. The British public was in for a huge treat.

In fact, The Royal Family is a comedy by George S. Kaufman and Edna Ferber that was first performed in 1927, and while it isn't quite as mouth-watering as the play I

imagined, it's still pretty good. Dench plays Fanny Cavendish, the matriarch of a theatrical dynasty that the authors based loosely on the Barrymore clan, the first family of Broadway. The action of the play revolves around Fanny's attempts to dissuade various members of her brood from giving up the pell-mell world of the theatre for a life of domestic drudgery.

When The Royal Family first came to London in 1930 the critics panned it, on the grounds that you had to know who the Barrymores were in order to enjoy it and few British people did. The same point was made by several reviewers when this revival opened last week, but I don't agree. Audiences are quite capable of recognising the types being portrayed on stage without knowing anything about the Bartymores. Tony Cavendish, for instance, who is energetically played by Toby Stephens, is a wayward matinee idol who could be any number of lovable Hollywood rogues, from Errol Flynn to Robert Downey Junior. The fact that he was originally based on John Barrymore is neither here nor there.

What is so charming about The Royal Family is that beneath the thin veneer of satire is an enormous amount of affection. Initially, the vanity and self-centredness of the Cavendishes make them seem rather unappealing, but by the end of Act II they've completely won you over. You wonder that anyone could think of abandoning life among this motley troupe for the cold banality of a more conventional existence. The two stuffed shirts who try and bully the matriarch's daughter and granddaughter into giving up their careers on the stage don't stand a chance.

This opposition between a warm, tightknit community of non-conformists and an emotionally sterile bourgeoisie is characteristic of all the best plays of the period, many of which were turned into classic Hollywood films. Nearly all of these plays — and the films they became — were written by New York Jews, and it doesn't take much of a leap to see in them a celebration of Jewish culture in contrast to the stodgy Christianity of white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. In The Royal Family, the virtues of the Jewish tradition are embodied by the character of Oscar Wolfe, the Cavendishes' wise old bird of a manager (beautifully played by Philip Voss). If the Cavendish clan has a patriarch, Wolfe is it, and he's infinitely more appealing than the stiff-necked cattle baron who tries to whisk Julie Cavendish (Harriet Walter) away to South America.

Jews are treated a good deal less sympathetically in the Royal Shakespeare Company's latest production of The Merchant of Venice. As directed by Loveday Ingram, Shylock is a villain of the first water and it takes all the ingenuity of Portia, played as a heroic mother-figure by Hermione Gulliford, to save Antonio and Bassanio from his clutches. This is an unashamedly feminist reading of the play, and, while it serves to enliven the courtroom confrontation between Shylock and Portia, the male principals are left so emasculated it's difficult to take them seriously as romantic figures. Bassani° (Paul Hickey), in particular, is so wet I was left scratching my head as to why this fire-breathing Portia shows any interest in him.

There are some superb performances, though. Ian Gelder invests Antonio with such authority I couldn't take my eyes off him and Ian Bartholomew's Shylock seethes with embittered hatred. However, the performer who really stands out is Chris Jarman, who has a brief cameo as the Prince of Morocco, one of Portia's unsuccessful suitors. His all too brief appearance, in which he leaps about the stage like one of the Arabian Knights, gives the play a much-needed boost of comic energy, and, after he's gone, it's almost as if someone's turned out the lights. A few more touches like that and this merely competent production of The Merchant of Venice might have turned into something much more memorable.

Toby Young's account of the five years he spent in New York, How to Lose Friends and Alienate People, has just been published by Little, Brown.

Previous page

Previous page