THE MIND OF A HOSTAGE

How I survived for two months as a captive in Beirut

CHARLES GLASS

As I sit in a corner of my dim cell lacing the seeds of the little light stretching them to these lines for you I was struck with the joy of a child: Beloved, With all the might of their hatred that tears this life apart They cannot put my mind in jail.

Fouzi al-Asmar, 'To the Beloved Motherland', in Poems from an Israeli Prison (Gazelle Publications) I ONCE asked Peter Niesewand, who while the Guardian correspondent in Rhodesia was held for months in solitary confinement by the Smith regime, how he had survived. Peter, who was as modest as he was talented, told me the secret was simply to think. There was no trick to mental survival beyond using the mind. I thought often of Peter during my 62 days' capitivity in Beirut this summer.

There was something about him after his im- prisonment that made him different from the rest of us. He was cal- mer, more reasonable, aloof from mundane concerns. He had been through an inconceiv- able ordeal. It was a tragedy when he died a few years ago, having become a successful novelist with every reason to live. He knew he was dying, and he prepared his wonderful wife, Nonie, and their children both spiritually and financially for his death. He was ready to die once, in a Rhodesian prison. What is solitary confinement but a pre- monition of purgatory?

I have written the detailed account of my captivity, which began on 17 June with the kidnapping and ended on 18 August when I escaped, in the Sunday Telegraph, the second instalment of which appears on Sunday. Even so I overwrote the article, giving poor James McManus 25,000 words when he asked for 10,000; I find my memory calling up still more events, more thoughts, more moments of fear and spir- itual contentment. I recall how one morn- ing, a young guard came into my bare room. He had come, as someone did nearly every day, to unlock the chain around my ankle and let me go to the lavatory. On that morning, he used both hands to open the lock. I could see down from my blindfold that he had put his pistol on the floor within my reach. It seemed to Charles Glass enjoying the sights of freedom in a New York park be a 7.62mm magazine-loaded pistol with a silencer on the end. I became nervous. Should I pick it up? If I did pick it up and he resisted, was I prepared to kill him?

He was 19 years old, one of six children of a Lebanese Shi'ite father and a Palesti- nian mother. We had spoken from time to time, when other guards were not there to warn him not to fraternise. He had taken the job at a monthly salary of L.£5 in a city which offered few if any other forms of employment. He once asked me if I had read Animal Farm. In the next room, watching television, was another young guard. He was about 24 and had been exceedingly kind to me, within the context of holding me prisoner. 'I'm sorry,' he said to me one day when I complained of being chained like an animal. 'No, please don't say that. You are not an animal. You are a good man. We are friends, you and I.' One of his friends, looking at a colour photograph of my family, had asked my permission to marry my fourteen-year-old stepdaughter, Beatrix.

This same guard had one evening decided to give me a special treat. While I sat blindfolded on the foam-rubber mat- tress on the floor I heard him moving things on wheels into the room. There was a mechanical commotion of clicking and whirring. 'Okay, Glass,' he said. 'Stand up.' I stood and he un- locked the chain around my ankle. Then he told me to sit in the middle of the floor. 'Okay, Glass. Take off blindfold, but don't turn around.'

When I took off the blindfold, I saw in front of me a television set connected to a cassette recorder. Then on came a video tape: Heartbreak Ridge with Clint East- wood. 'Good movie, Glass? You like Clint Eastwood?'

Another of the boys told me my hair was getting too long, especially for the summer heat. 'You want haircut?' On a kind of honour system, I kept my eyes closed while he clipped away. 'Good haircut, no? Not finished yet. Now, shave.' He took out a shaving brush and gave me a barber shop shave. It felt wonderful.

The same boy sat on my mattress one afternoon, probably because he was as bored and lonely as I was, for a chat. 'Are girls beautiful in London?'

'Very.'

'If I go London, you think girl marry me?'

'There are a lot of Lebanese girls in London. Do you want to marry a Lebanese?'

'No. I want marry English girl. You think she marry me?'

'Well, what do you look like? Are you handsome?'

'Not handsome, no. Not ugly. Average, like you.'

Most of the guards would usually give me uninteresting food, which did not bother me. I had no appetite. One guard, who said he had worked in a restaurant, liked to make me special treats: pasta, rice with vegetables or chicken with garlic. One of the more senior members of the orga- nisation who would come from time to time to interrogate me or to try to make me say I worked for the CIA reprimanded him for treating me too well.

One day, a guard in a fit of rage kicked me. When I told the other guards about it, he was taken away. He never returned.

There was a regular changing of the guards, no doubt to avoid the possibility of friendship between hostage and captor and perhaps also because it is a dull job. The guard cooks and cleans up after the hos- tage, but spends most of his time sitting around. Usually, there were only two guards in any of the four apartments where I was held. In the place I was held the longest, there was a woman and small baby during the week — what I suspected was an effort to persuade the neighbours that a family lived there. I loved to listen to the mother talking to the baby, whom I gues- sed to be a six-month-old girl. Sometimes, she would be gentle and loving. `Oooh, Samira', she would say. `Ya, ya, ya, ya. . .' Occasionally the mother, who couldn't have been more than 17 herself, would lose patience with the baby's crying: 'Enough, Samira. It's enough.' She also sang to the child. The woman and child never came into my room, but I could hear them on weekdays; I was told that at the weekends they went home.

Most of the guards were secular, which surprised me. Their ambitions were any- thing but religious: they wanted new cars, liked drinking whisky and dancing, longed for women. There were occasional guards who 'prayed, as devout Muslims should, five times a day. When I would be praying silently to my God — the Father, Son and Holy Spirit — I could hear one guard in the next room praying out loud to his. Could God hear us both at the same time? Whose prayers would He answer — his or mine? I tried not to feel pride or vanity, but believed that wherever an oppressor and his victim pray, God listens to the victim. This would be true for the guard and me, just as in another context it would be true for Israeli prison guards and their Lebanese prisoners, or for Nazi murderers and Jewish captives.

The guards would leave me alone most of the time. During the long period when I had no books, I sat quietly alone on my mattress. I thought of Peter Niesewand's prescription and used my mind. I channel- led my thought along certain specific lines, and whenever I found myself day- dreaming, I would resume thinking about one of the six things.

My family: I would talk to them in my thoughts or imagine what they were doing at any time of the day. More than anything else, I wanted to end their suffering. One day, I had the distinct impression my nine-year-old son, George, was crying at school. The impression was so strong that I cried myself and tried to tell him not to worry, that I was alive and would soon be home. My wife, Fiona, told me when I came home that George had indeed been crying at his school, but — before I turn to mysticism — I must admit it is impossible for me to know whether my sensation and his crying took place on the same day. I would spend each day in my imagination with a different member of my family; as though they were taking turns baby-sitting. Telepathy:I had met a wonderful character in Damascus a few months earlier named Docteur Solomon. He was a magician out of a Fellini film, gregarious, funny, doing tricks and chattering in six languages, telling us how to eat if we wanted to live to his ripe old age of 82. He was the uncle of a friend of mine, and the high point of his performance was mind-reading. Almost every day in my room, I would think, Docteur Solomon, Docteur Solomon, c'est Charles Glass qui vous appelle. Aidez-moi.' I would describe my location as best I could and urge him to tell the Syrian army.

Thinking back on it, I would love to be a screenwriter constructing a scene in which an 82-year-old magician enters the office of the head of Syrian military intelligence to tell him where an American hostage is held. 'Don't call us, Doctor. We'll call you.'

The strange thing about the telepathy is that Fiona, who is ordinarily not given to faith healing, astrology or tarot cards, was in touch through a friend with two psychic women in the United States. One told Fiona that I was having difficulty getting enough water to drink, which I was, and that my captors were translating my note- books into Arabic, which they were. This was before anyone knew I'd had my suitcase with me when I was taken. One clairvoyant told her I would escape in mid-August and the other said I would arrive home on 19 August – which I did.

These women would take no money. I have an open mind now on clairvoyance. If God gave me the gift of eyesight, why shouldn't he have given some people other gifts as well?

A novel: I wrote two novels on pages in my mind. The first was about two writers, one English and the other American, who are touring the Levant in search of its essence. They never meet, but their paths cross, just as they cross those of writers in other countries. Each stands in a way for an imperial ideal: the now less innocent Quiet American, treading in the wake of a departed Pax Britannica, both lost and degenerate in a Levant which has not recovered from its own tribalism and cen- turies of foreign domination. The heroine is a beautiful Armenian who, though abused in different ways by each man, triumphs over them both. Most of the story takes place in Crusader country around Aleppo and north Lebanon, but, not sur- prisingly, there is a kidnapping. (Pub- lishers who can bear this story may call my agent, Gillon Aitken.) The other book is about a young man who decides to become a priest and wreaks havoc in the lives of his family, his pregnant girl friend and the Society of Jesus. I was on the third or fourth chapter of this one when I escaped. Now, I've lost interest.

My life: I've led a troubled life, and it seemed to me I should relive it to deter- mine where I'd gone so wrong that I was blindfolded and chained helpless to a wall. I began with my earliest memory, which is, not surprisingly, of pain: at the age of three, I had burned my hand on an iron and run screaming into the road. I remem- bered my cocker spaniel, Bobo, who had been killed by a car when I was four, and I followed the course of my life, not seeking Meaning, up to the moment I was kidnap- ped. Like a man when he joins Alcoholics Anoymous, I had to get out of my prison to make amends: I had to beg the forgiveness of some people and forgive others. So often they were the same people: those I had wronged were those who had wronged me. And I thought of all those important figures in my life ' who were now dead. Where were they? Could they hear me? Would they know I loved them? I noticed how my life had changed — how I tasted happiness — when I got married.

Prayer and meditation: It took most of 62 days, but I learned how to pray. I began in the early days to recite the prayers I'd learned as a child and to ask God to deliver me. I promised to amend my life, to help others, to become more spiritual if he would only let me go. I did not care how I became free: a rescue, a deal, an escape or divine interventions. I just wanted to go home. I later tried to couch my desire to be free in terms of wanting it for the good of other people, namely, Fiona and the chil- dren, But it was not until I prayed sincerely for others that a kind of spiritual peace descended on me. Very early on in my captivity, my captors announced I was being set free that night. In the event, they merely moved me to another location. When I recall how I felt at the thought of going free after ten days, the vanity with which I greeted the prospect, I realise I was not ready. I had learned nothing. It took

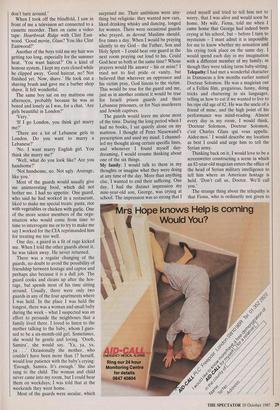

A haggard Charles Glass pictured in Damascus on his way home after his release

time for the seed of prayer to grow. Too often, my conscience was torn when I was praying: how could I pray for my family and not for the families of the other foreign hostages? How could I pray for the foreign hostages and not for the Lebanese and Palestinians? How could I not pray for the seven Israeli prisoners held incommunica- do in Lebanon? What about captives everywhere else in the world? When I would pray for all these others, my consci- ence would nag at me: you have a duty to pray for your family. With a Catholic conscience you can never win. Nor should you.

Escape: Every day, I would have to think of a way in which I could do something to get out. This might involve writing a note to be forced out of the bathroom fan, or digging a hole in the wall in the hope of passing a note to the apartment next door, or manipulating my chains, or trying to pick a lock. I believed I had a moral duty to my family to escape, no matter what the risk. My great fear was that my children would in this life or the next ask me, 'Didn't you do everything possible to get home?'

When it came to doing everything possi- ble to escape, did I have the right to use violence? Should I pick up that gun, I asked myself, even if it meant killing these boys and possibly dying myself, with all the pain this would cause all our families? I wondered whether Jesus, if He had been held captive while He was on his way to Jerusalem to fulfil the destiny that would be the salvation of mankind, would have killed his guards. Where did His duty lie? The fifth commandment says, 'Thou shalt not kill,' without any qualifications or exceptions. But should the Salvation of mankind have been lost because highway- men in Palestine had kidnapped our Lord and He was too conscientious to kill them? I decided our Lord would have had to fall back on a miracle, perhaps sending them to sleep or vanishing before their eyes, rather than kill them.

I did not touch the pistol, and the guard finished locking me up.

A month later, when my guards went to sleep, a miracle delivered me to the family who had waited so long and patiently for my return.

When I took my children to Mass, my first Sunday home, the priest read Psalm 68: 'God setteth the solitary in families: He bringeth out those which are bound with chains: but the rebellious dwell in a dry land.'

Previous page

Previous page