Drowning in shallow water

Francis King

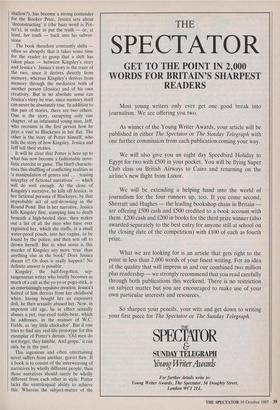

BLACKEYES by Dennis Potter

Faber, £8.95

Recently a Japanese, last seen in Kyoto, rushed up to me at the National Theatre, crying out, not in annoyance but in gratitude, 'Mr King, Mr King! You stole me, you stole me!' Stealing' him had consisted of basing a minor character in a short story on him. In this sense Maurice James Kingsley, a 77-year-old author, has stolen his niece, a model called Jessica, for the central character, Blackeyes, of the novel, Sugar Bush, which has amazed everyone, not least Kingsley himself, by its success. (As Potter puts it: 'He had not sunk so low as to have one of his now very occasional Occasional Pieces rejected by the Spectator or accepted by the Daily Telegraph, but there had been little hint that his dried-up old frame was going to produce such a late bloom').

But if Kingsley has stolen his niece, she, in the manner of one of those people who deliberately leave out money on a table in the hope of incriminating a maid or a cleaner, has all but forced him to do so. She has done this in the expectation that he will suffer the humiliation of having the resulting novel, so far outside the range of 'a rather unsavoury eccentric with odd opinions, bizarre habits, and dated, almost fin-de-siècle mannerisms', either rejected or dismissed with scorn by reviewers. When, on the contrary, his tale of a model from her first audition to her suicide, ten years later, by drowning in the Round Pond (surely a difficult feat in waters so shallow?), has become a strong contender for the Booker Prize, Jessica sets about 'deconstructing' it (the buzz word is Pot- ter's), in order to put the truth — or, at least, her truth — back into his subver- sions.

The book therefore constantly shifts — often so abruptly that it takes some time for the reader to grasp that a shift has taken place — between Kingsley's story and Jessica's. Jessica's story is the truer of the two, since it derives directly from memory, whereas Kingsley's derives from memory through the mediation both of another person (Jessica) and of his own creativity. But in no absolute sense can Jessica's story be true, since memory itself can never be absolutely true. In addition to this pair of stories, there are two others. One is the story, occupying only one chapter, of an infatuated young man, Jeff, who recounts in the first person how he pays a visit to Blackeyes in her flat. The other is the story of Potter himself, who tells the story of how Kingsley, Jessica and Jeff tell their stories.

It will be clear that Potter is here up to what has now become a fashionable nove- listic exercise or game. The blurb characte- rises this shuffling of conflicting realities as 'a manipulation of genres and. . . teasing interplay of fictional narratives' — which will do well enough. At the close of Kingsley's narrative, he kills off Jessica, in her fictional persona of Blackeyes, by that improbable act of self-drowning in the Round Pond. But in her narrative, Jessica kills Kingsley first, stamping him to death beneath a high-heeled shoe; then makes out a list of all the men who have ever exploited her, which she stuffs, in a small water-proof pouch, into her vagina, to be found by the police; and then sets off to drown herself. But in what sense is this murder of Kingsley any more 'true' than anything else in the book? Does Jessica dream it? Or does it really happen? No definite answer is possible.

Kingsley, the half-forgotten, sep- tuagenarian writer who briefly becomes as much of a cult as the yo-yo or pogo-stick, is an entertainingly repulsive creation. Jessica's hatred of him derives from her childhood when, having bought her an expensive doll, he then sexually abused her. Now, in impotent old age, he in effect sexually abuses a pet, one-eyed teddy-bear, which he addresses, in the manner of W.C.

Fields, as 'my little chickadee'. But if one tries to find any real-life prototype for this exemplar of Potter's dictum, 'Old men do not forget, they fumble. And grope,' it can only be in the past.

This ingenious and often entertaining novel suffers from another, graver flaw. If a book is to consist of the interweaving of narratives by wholly different people, then those narratives should surely be wholly different from each other in style. Potter lacks the ventriloquial ability to achieve this. Whereas the subject-matter of the narratives varies brilliantly, their styles hardly do so. The rhythms have the same kind of choppiness, the images spring the same kind of brutal surprises. This sense of sameness is fatal.

Blackeyes is at once nobody and all body. In creating her out of the stuff of Jessica and his perverted dreams, Kingsley has produced what is, in effect, a beautiful doll, as incapable of an orgasm (as she repeatedly tells people) as of any true emotion. Jessica herself hardly seems more real, except in that final act of revenge against all the men, Kingsley above all, who have exploited her.

Except when the works cough up an occasional spanner — for example 'like' used instead of 'as' as a conjunction — this is a meticulously engineered book, full of acrid satire at the expense of the literary world and advertising. It also has a lot of interest to say on the fashionable subject of male exploitation of women and, in par- ticular, of beautiful women. (At one point, a woman says to Blackeyes, 'Don't you think you'd be better off in bed, my dear?' This is what, in effect, men are constantly saying to her). But it remains a book more to puzzle over than to enjoy, more to admire for the dexterity of its dissection of the dead than to love for the eloquence of its celebration of the living.

Previous page

Previous page