South of the border

Gavin stamp ln the next decade it is very likely that the aPPearance of London may be changed almost out of recognition. Paradoxically, at a time of depression and high unemployMent, London is experiencing its third Office property boom since the war. This is a boom fuelled by Middle Eastern money as well as by large institutional investors, anxious to put their overflowing funds into something substantial. In a recent article in the Architects' Journal, Charles Knevitt estimated that ten million square feet of new office space is currently proposed for London at a cost of £1,200 million. What is remarkable about these developments is that they are proposed not for the conventional sites in thc City or the West End, but for the banks of the Thames. This his means principally the South Bank, for so long neglected, from Battersea Bridge to Tower Bridge and beyond; and the figures given above do not include the massive „redevelopment of the Surrey Docks proPosed by Lysander Estates (architect: Richard Seifert and Partners) and approved by Southwark Council. The notorious 'Green Giant', a proposed 500-foot tower uPposite the Tate Gallery which was narrowly averted last year, was but one of many schemes for tall office buildings by the river. The Thames may soon be flowing past a line of towers, and the famous vistas along and across the river towards Westminster and St Paul's will be only a memory. Michael Heseltine, the Secretary of State for the Environment, is evidently well aware of the potentially disastrous scale of the developments proposed, and he has committed himself to establishing a development policy for the Thames in central London, so as 'to ensure that new buildings are of a high architectural standard and that development schemes as a Whole contribute positively to the visual and Other amenities of the river-side . I hope !hat developers, architects and others involved in the development process will respond to the challenge.' One way of making them respond to that challenge is to hold public inquiries about all the important developments. That for tbhe all the important developments. That for tbhe Hay's Wharf site, opposite the City etween London and Tower Bridges, began rowdily last month, with local opposition very evident. The plan is for 1,930,000 square feet of offices with a 21-storey tower as well as housing, industrial premises and a Park, to cost £200 million. An inquiry for the Effra site, next to the GreenGiant site at the end of Vauxhall Bridge, has also just begun (a park, industrial premises, houses and 370,000 square feet of offices rising up to 21 storeys) and this week another inquiry has opened into the new proposals for the Coin Street site in Waterloo. Many other schemes have not yet reached planning permission stage. Some are very fanciful, not to say lunatic; Richard Seifert, for instance, proposes a new 'City Bridge' between Hay's Wharf and Billingsgate, which will be a block higher than Tower Bridge and will contain shops, an ice rink, a pub and — oh yes — a million square feet of office space.

It is as if London has suddenly become aware of the River Thames which has been flowing peacefully by for so long: that it has a South Bank as well as a North Bank. For decades, the docks, warehouses, factories and wharves by the river — those agents and products of London's former wealth and glory — have been redundant and derelict. South (like East) London has always been industrial and the view across the Thames of South London has always been very different in character from the panorama of London from the South Bank. Now, almost for the first time, developers have become aware of the potential of the shabby industrial littoral of South London. What is so depressing about these proposals is that they reflect a North London perspective — a view of the South Bank as an uninteresting and alien area on which to dump whatever sort of building is thought to be necessary or 'profitable. All these schemes ignore South London's own distinct history and interesting character.

Until recently, there was a general unawareness of the proximity and convenience of South London, a frequent refusal to acknowledge how close it is to the West End and to the centres of government and business. This was an attitude of long standing and one which prevails still with many people and so may (I hope) militate against the sudcess of these South Bank development schemes. The fact is that London is not equally divided by its river, like Buda-Pest; nor is it a united homogeneous city like Paris or Rome through which a river flows. The Thames is a barrier. The Underground system hardly penetrates south of the river. South Londoners rely on buses and on the recondite ramifications of the surface railways of the former Southern Electric. The history of South London is, of course, rather shorter than that of London. Until as late as 1750, when Westminster Bridge was opened, the Thames was crossed only by London Bridge and the only concentration of buildings on the low, marshy South Bank was in Southwark — the 'south works' at the end of the bridge. The building of Blackfriars Bridge in the 1760s and of Southwark, Waterloo and Vauxhall Bridges after the end of the Napoleonic wars opened up South London for housing developments of a standard Georgian type and, for a while, the area was almost respectable.

The railways ruined the area. Slums grew up behind Waterloo Station (opened 1848), and the tangle of railway viaducts which threaded their way over the low-lying land allowed the more prosperous to move out to Sydenham and Norwood and so let Waterloo and Southwark become notoriously poor and rough by the end of the century. The Thames itself became lined, with wharves and warehouses and the industrial character of the South Bank was proudly proclaimed by the Shot Tower and the Lion Brewery, until both were demolished for.the Festival of Britain and its successors.

For architects and planners this century, South London has been nothing but an area ripe for redevelopment. The English dislike of the inner city and desire for the country or outer suburb became enshrined in the Garden City ideal, which encouraged the decanting of the poorer classes out of the dense, dirty centre of London rather than the rebuilding of existing housing (which the LCC and the charitable housing trusts were undertaking). It also reinforced the idea of 'zoning', the separation of func tions, of work from residence, which has dominated most 20th-cent9ry schemes of town planning. Only recently has it been realised that decentralisation and wholesale redevelopment can be utterly destructive and inimical to city life, while the Complex pattern of small-scale housing, shops and workshops, typical of old South London, can now be seen as desirable and healthy.

This zoning policy and these attitudes have persisted since 1945 and are respons ible for the present state of the South Bank.

Small industries have been discouraged, bombed sites have not been rebuilt, shops and housing have been allowed to disappear and those committed Socialist councils in Lambeth and Southwark have been happy to permit commercial developments in the north parts of their boroughs so as to pay for council housing elsewhere. Lambeth has now come to its senses, but the leader of Southwark Council, John O'Grady, has said: 'This is a commercial city and there is a desire for offices. If we don't build them here they will only go to Brussels'. But what happens to the South Bank is not just Southwark's and Lambeth's problem; it can adversely affect all Londoners if the centre of the city is denuded of cheap housing for an ordinary working population. It leads to higher prices, greater inefficiency and the decline of services.

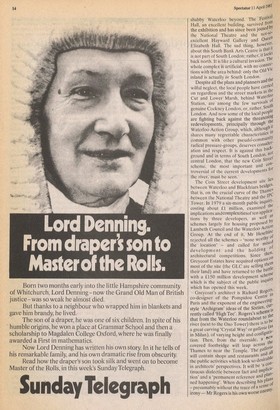

The most conspicuous change since 1945 has been the development of the South Bank as an 'Arts Centre'. This began with the 1951 Festival of Britain, which replaced many streets of houses which had survived the Blitz and which, most significantly, had on the south perimeter a carefully designed screen to shield visitors from the sight of shabby Waterloo beyond. The " Festival Hall, an excellent building, survived front the exhibition and has since been joined bY the National Theatre and the not-so' excellent Hayward Gallery and Queen Elizabeth Hall. The sad thing, however, about this South Bank Arts Centre is that it is not part of South London; rather, it looks back north. It is like a cultural invasion. The whole complex is artificial, with no connections with the area behind: only the Old Vie inland is actually in South London. Despite all the plans and planners and the wilful neglect, the local people have carried on regardless and the street markets in the Cut and Lower' Marsh, behind Waterloo Station, are among the few survivals °I genuine Cockney London, or, rather, South London. And now some of the local peoPle are fighting back against the threatening redevelopments, principally 'through the Waterloo Action Group, which, although It shares many regrettable characteristics in common with other pseudd-communitY radical pressure-groups, deserves consideration and respect. It is against this background and in terms of South London, n°t central London, that the new Coin Street scheme, the most important and ontroversial of the current developments the river, must be seen. The Coin Street development site lies between Waterloo and Blackfriars bridges' that is, on the crucial curve of the Tharnecs between the National Theatre and tIle I,P Tower. In 1979 a six-month public inquitY' costing about fl million, examined the implications andcomplexitiesof ten apPlications by three developers, as well as for schemes largely for housing proposed bY Lambeth Council and the Waterloo Action Group. At the end of it, Mr Heseltine rejected all the schemes – 'none worthY °di the location' – and called for tnIxe f development and the holding ° architectural competitions. Since then' Greycoat Estates have acquired options °11 most of the site (the GLC are selling then/ their land) and have returned to the Wile. with a £1 50 million development schente which is the subject of the public incluirY which has opened this week. Greycoat's architect is Richard Roger.s. co-designer of the Pompidou Centre In Paris and the exponent of the engineering 0. style `Archigram' ideas of the Sixties, rently called `High Tee. Rogers's sChChe that from the Waterloo roundabout to river (next to the Oxo Tower) there is to he a great curving 'Crystal Way' or galleria in Milan), of varying height and configuration. Then, from the riverside, a he covered footbridge will leap across the Thames to near the Temple. The gaild'klit will contain shops and restaurants and 11, the public activities which look so desirabie in architects' perspectives. It will be 'a Ontinuous dialectic between fact and intPlic3tion' and a 'permanent reference and pion-i Fled happening'. When describing his Plan, – presumably without the trace of a sense °' irony— Mr Rogers is his own worse enenlY. Worst of all, he envisages the development as a 'fun area'. Whether the purpose of architecture is to be 'fun' is an interesting question; whether Londoners or local People will find his buildings 'fun' is a more 1 Portant question. But the Coin Street scheme is not just for fun. The developers have been very clever: It is a 'mixed' development. As well as shops and bars and an 'amphitheatre', there is to be 200,000 square feet of housing and 30,000 square feet for light industrial use, but the real meat is the 995,000 square feet ,of office space, housed in towers varying in ,neight from seven to 16 storeys. What is in iaet being proposed is a third of a mile of 'Lego' type buildings which will be visually Prominent from over the river and which lIll confirm the tendency to make the South Bank commercial in character. The local Lambeth naturally oppose the scheme, while, Lambeth and Southwark Councils remain ainbivalent. Another critic is Sir Denys Lasdun, who feels that Rogers is concerned Only with interior and not with exterior space and that the buildings will not help to create the 'Theatre Square' — the place of civic character he hopes to see behind his National Theatre: even though the blank back of his building is a quintessential example of north-looking South Bank architecture.

What Mr Rogers is proposing is, in fact, not really new. Even with the public areas, the Greycoats scheme is an office development and, as such, dresses up the planning ideas of the Forties and with the fashionable architectural enthusiasms of the Sixties. It may well have an unfortunate effect on the view of the City from Westminster along and across the curve of the Thames. The biggest objection, however, must be that it is much too large. All the schemes being proposed for the South Bank are too big and will go up too quickly: no architect has ever been able to work successfuly on such a scale. The Secretary of State, through the development policy he promises, can have an effect here by breaking down the size of the schemes and by insisting on genuine mixed development for it is vital that inner South London retains a high proportion of housing. To replace housing by offices will destroy the special and distinct character of the South Bank. The current development proposals are infinitely worse than the neglect and contempt from which South London has suffered for so long.

Previous page

Previous page