Exhibitions 1

A new view of India

Ruth Guilding

Tigers Round the Throne: the Court of Tipu Sultan (1750-1799) (Zamana Gallery, till 14 October)

South Asian culture has always con- jured a powerful mixture of feelings in the European bosom, fascination mingling with repulsion. Imperialist policies and ideas were already being practised among 18th-century Anglo-Indians and officials of the East India Company long before Queen Victoria learned to call herself `Empress of All India'. While true patriots returned to their homeland from service with a sigh of relief, certain nabobs shock- ed Georgian society by going native and staying on, while others returned to build country houses with Mogul domes and 'Hindoo' arches in which were installed native wives and half-caste children, and have their portraits painted puffing on a hookah. Museums of Indian art in this country have tended towards the imperial- ist view, failing to explore fully her indige- nous traditions. Enlightenment began to glimmer in 1947 when the Royal Academy marked India's independence celebrations with an exhibition of her art. Re-education of public taste was the attested aim and, with a confessional note, the catalogue stated that the net influence of imperialist policies on India was the total decline of her arts and crafts and the demoralisa- tion of the native consciousness. Educa- tion, and the accurate representation of

historical fact, became the watchword when the V & A showed an exhibition of Mogul art as part of its contribution to the Festival of India.

The V & A houses the oldest and most comprehensive collection of Indian art outside India itself, the nucleus being the collections of the East India Company, bought by Henry Cole in 1851. To mark the centenary of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, its new Nehru Gallery of Indian Art will open in November, and will exhibit a portion of the fabulous collections which have languished in storerooms until now. The plans and elevations for the gallery promise an impressive architectonic space, with natural materials brought from India for stone floors and wooden screens, and ancient architectural fragments incorpo- rated into the scheme.

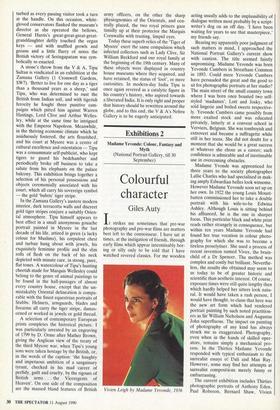

As well as presenting India's indigenous arts afresh, the V & A will also seek to represent the transformations of and influ- ences on this art born of exposure to other cultures. An object which falls into this category provided the dramatic climax of a recent press launch for the new gallery, and reporters and curators jostled one another for a better view. The gruesome `tyger- man-organ' of Tipu Sultan, captured by General Harris after Tipu's defeat and death at Seringapatam, was played in a final concert, before being enshrined in an atmospherically controlled glass case for posterity. This wooden automaton, carved to resemble an English soldier being mauled to death by a tiger, was first displayed in the East India Company's museum in 1808, where scholars in the adjoining library were thoroughly dis- 'Tipu's Tiger' mauls an Englishman with muffled roars and groans at the V & A turbed as every passing visitor took a turn at the handle. On this occasion, white- gloved conservators flanked the museum's director as she operated the bellows, General Harris's great-great-great-great- granddaughter deftly touched the organ keys — and with muffled growls and groans and a little flurry of notes the British victory of Seringapatam was sym- bolically re-enacted.

A stone's throw from the V & A, Tipu Sultan is vindicated in an exhibition at the Zamana Gallery (1 Cromwell Gardens, SW7). 'Better to live for one day as a tiger than a thousand years as a sheep,' said Tipu, who was determined to oust the British from Indian soil, and with tigerish ferocity he fought three punitive cam- paigns which pitted him against Warren Hastings, Lord Clive and Arthur Welles- ley, while at the same time he intrigued with the Emperor Napoleon. Meanwhile, in the thriving economic climate which he assiduously fostered, the arts flourished, and his court at Mysore was a centre of cultural excellence and ostentation — Tipu was a consummate self-publicist, who kept tigers to guard his bedchamber and periodically broke off business to take a salute from his elephants on the palace balcony. This exhibition brings together a selection of his personal possessions and objects ceremonially associated with his court, which all carry his sovereign symbol — the gold `hubris' tiger stripe.

In the Zamana Gallery's austere modern interior, dark terracotta walls and discreet gold tiger stripes conjure a suitably Orien- tal atmosphere. Tipu himself appears to best effect in a small anonymous gouache portrait painted in Mysore in the last decade of his life, attired in green (a lucky colour for Muslims), his corpulent chest and turban hung about with jewels, his exquisitely feminine profile and the slim rolls of flesh on the back of his neck depicted with minute care, in strong, pure, flat tones. A watercolour of Tipu's hunting cheetah made for Marquis Wellesley could belong to the genre of animal paintings to be found in the hall-passages of almost every country house, except that the un- mistakably Oriental delineation is compa- rable with the finest equestrian portraits of Stubbs. Helmets, armguards, blades and firearms all carry the tiger stripe, damas- cened or worked in jewels or gold thread.

A selection of contemporary European prints completes the historical picture. I was particularly arrested by an engraving of 1799 by D. Orme after Mather Brown, giving the Anglican view of the treaty of the third Mysore war, when Tipu's young sons were taken hostage by the British, or, in the words of the caption: 'the haughty and impetuous ambition of a sanguinary tyrant, checked in his mad career of perfidy, guilt and cruelty, by the rigours of British arms . . the Viceregents of Heaven'. On one side of the composition are the massed bland features of British army officers, on the other the sharp physiognomies of the Orientals, and cen- trally placed, the two royal princes gaze timidly up at their protector the Marquis Cornwallis with trusting, limpid eyes.

Today these superb relics of the 'Tiger of Mysore' exert the same compulsion which infected collectors such as Lady Clive, Sir William Beckford and our royal family at the beginning of the 19th century. Many of these objects were displayed in country house museums where they acquired, and have retained, the status of 'loot', or mere curiosities. In modern-day India Tipu is once again revered as a catalytic figure in his country's history, who aspired towards a liberated India. It is only right and proper that history should be rewritten around the globe, and to this end, the V & A's Nehru Gallery is to be eagerly anticipated.

Previous page

Previous page