Exhibitions

Victor Pasmore (Serpentine Gallery, till 27 May) 15 June)

Mind over matter

Giles Auty

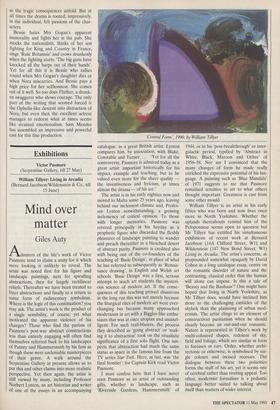

Admirers of the life's work of Victor Pasmore tend to claim a unity for it which mere looking is unlikely to reveal. The artist was noted first for his figure and landscape paintings, next for spiralling abstractions, then for largely rectilinear reliefs. Thereafter we have been treated to freer abstractions and finally to a return to some form of rudimentary symbolism. Where is the logic of this continuation? you may ask. The artist's work is the product of a single sensibility, of course, yet what motivated the apparent violence of his changes? Those who find the purism of Pasmore's post-war abstract constructions less than entirely engaging will often find themselves referred back to his landscapes of Putney and Hammersmith by his fans as though these were undeniable masterpieces of their genre. A walk around the Serpentine Gallery at present allows us to Put this and other claims into more realistic perspective. Yet then again, the artist is still viewed by many, including Professor Norbert Lynton, an art historian and writer of one of the essays in an accompanying `Central Form' 1990, by William Tillyer catalogue, as a great British artist. Lynton compares him, by association, with Blake, Constable and Turner. . . . 'Yet for all the controversy, Pasmore is admired today as a great artist: important historically for his impact, example and teaching, but to be valued even more for the sheer quality the inventiveness and lyricism, at times almost the drama — of his art.'

The artist is in his early eighties now and moved to Malta some 25 years ago, leaving behind our inclement climate and, Profes- sor Lynton notwithstanding, a growing inclemency of critical opinion. To those with longer memories, Pasmore was revered principally in his heyday as a prophetic figure who discarded the fleshly pleasures of landscape painting to wander and preach thereafter in a bleached desert of abstract purity. Pasmore is credited also with being one of the co-founders of the teaching of 'Basic Design', in place of what he has referred to subsequently as 'Renais- sance drawing', in English and Welsh art schools. 'Basic Design' was a first, serious attempt to teach art students the mysteri- ous science of modern art. If the conse- quences of this teaching proved disastrous in the long run this was not merely because the liturgical rites of modern art were ever- changing but because many approached modernism in art with a Biggles-like enthu- siasm that was at once utopian and unintel- ligent. For such trail-blazers, the process they described as 'going abstract' or 'mak- ing it to abstraction' took on the ritualistic significance of a first solo flight. One sus- pects that abstraction had much the same status as space in the famous line from the TV series Star Trek. Here, at last, was 'the final frontier'; for Captain Kirk read Victor Pasmore.

I must confess here that I have never seen Pasmore as an artist of outstanding gifts, whether in landscape, such as `Riverside Gardens, Hammersmith' of 1944, or in his 'post-breakthrough' or inter- galactic period, typified by 'Abstract in White, Black, Maroon and Ochre' of 1956-58. Nor am I convinced that the many changes of form he made really enriched the expressive potential of his lan- guage. A painting such as 'Blue Mandala' of 1971 suggests to me that Pasmore remained sensitive in art to what others thought important. Greatness is cast from some other mould.

William Tillyer is an artist in his early fifties who was born and now lives once more in North Yorkshire. Whether the uplands thereabouts remind him of the Peloponnese seems open to question but Mr Tillyer has entitled his simultaneous exhibitions of recent work at .Bernard Jacobson (14A Clifford Street, W1) and Wildenstein (147 New Bond Street, W1) Living in Arcadia. The artist's concerns, as propounded somewhat opaquely by David Cohen in a long catalogue essay, centre on the romantic disorder of nature and the contrasting, classical order that the human will alone can impose. Is this a tale of `Beauty and the Bauhaus'? One might have hoped that living in North Yorkshire, as Mr Tillyer does, would have inclined him more to the challenging canticles of the skylark than the plainsong of urban mod- ernists. The artist clings to an element of constructivist puritanism when he should clearly become an out-and-out romantic. Nature is represented in Tillyer's work by multi-coloured shapes, redolent of sky, field and foliage, which are similar in form to foetuses or ears. Order, whether archi- tectonic or otherwise, is symbolised by sin- gle colours and incised recesses. The dialogue between these two polarities forms the stuff of his art, yet it seems one of cerebral rather than riveting appeal. Too often, modernist formalism is a pedantic language better suited to talking about itself than matters of wider interest.

Previous page

Previous page