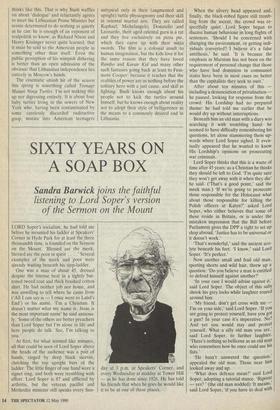

SIXTY YEARS ON A SOAP BOX

listening to Lord Soper's version of the Sermon on the Mount

LORD Soper's socialism, he had told me before he mounted his ladder at Speakers' Corner in Hyde Park for at least the three thousandth time, is founded on the Sermon on the Mount. 'Blessed are the meek, blessed are the poor in spirit . . . .' Several examples of the meek and poor were already waiting beneath his step-ladder.

One was a man of about 45, dressed despite the intense heat in a tightly but- toned tweed coat and thick brushed cotton shirt. He had neither job nor home, and was unwilling to tell where he came from ('All I can say is — I once went to Land's End') or his name. 'I'm a Christian. It doesn't matter what my name is, Jesus is the most important name' he said anxious- ly. 'Some of the others are better preachers than Lord Soper but I'm alone in life and here people do talk. See, I'm talking to you.'

At first, for what seemed like minutes, all that could be seen of Lord Soper above the heads of the audience was a pair of hands, ringed by deep black sleeves, clutching the top upright bars of the ladder. The little finger of one hand wore a signet ring, and both were trembling with effort. Lord Soper is 87 and afflicted by arthritis, but the veteran pacifist and Methodist minister still speaks every Sun-

day at 3 p.m. at Speakers' Corner, and every Wednesday at midday at Tower Hill — as he has done since 1926. He has told his friends that when he goes he would like it to be at one of these places. When the silvery head appeared and, finally, the black-robed figure still tremb- ling from the ascent, the crowd was re- spectfully quiet. Lord Soper began to discuss human behaviour in long flights of sentences. 'Should I be concerned with changing the environment, or getting indi- viduals converted? I believe it's a false antithesis,' he said. 'It is because the emphasis in Marxism has not been on the requirement of personal change that those who have had dominion in communist states have been in most cases no better than the capitalists they seek to oust.'

After about ten minutes of this including a denunciation of privatisation — he paused, looking for response from the crowd. His Lordship had no prepared theme: he had told me earlier that he would dry up without interruptions.

Beneath him an old man with a diary was searching it with trembling hand: he seemed to have difficulty remembering his questions, let alone stammering them up- wards where Lord Soper sighed. It even- tually appeared that he wanted to know His Lordship's opinions on prosecuting war criminals.

Lord Soper thinks that this is a waste of time after 45 years: as a Christian he thinks they should be left to God. 'I'm quite sure they won't get away with it when they die' he said. (`That's a good point,' said the meek man.) 'If we're going to prosecute those responsible for the Holocaust what about those responsible for killing the Polish officers at Katyn?' asked Lord Soper, who either believes that some of these reside in Britain, or is under the mistaken impression that the Bill before Parliament gives the DPP a right to set up shop abroad. 'Justice has to be universal or it doesn't work.'

`That's wonderful,' said the ancient aco- lyte beneath his feet. 'I know,' said Lord Soper. 'It's perfect.'

Now another small and frail old man, sporting shorts and wild hair, threw up a question: `Do you believe a man is entitled to defend himself against another?' 'In your case I would advise against it,' said Lord Soper. The object of this sally shook his grey locks while laughter roared around him.

'My friend, don't get cross with me I'm on your side,' said Lord Soper. 'If you are going to protect yourself, have you got a gun? In your case it's imperative. No? And yet you would stay and protect yourself. What a silly old man you are, said Lord Soper, to further laughter. 'There's nothing so bellicose as an old man who remembers how he once could use his fists.'

'He hasn't answered the question,' appealed the old man. Those near him looked away and up.

'What does defence mean?' said Lord Soper, adopting a tutorial stance. 'Riposte, — yes? ' (the old man nodded) 'It means,' said Lord Soper, `if you have to deal with someone and he has a billiard cue, then you must get a larger one: the gospel of the larger and better billiard cue.' You agree with me, but you don't understand the word,' Lord Soper graciously informed him. (His Lordship is known among friends as Dr Soper and his Who's Who entry shows that he is an MA Cantab and DPhil, as well as an Honorary Fellow of St Catherine's College, Cambridge.) 'What disables a man', he asked, a moment later, having moved on to the subject of class distinction and unfair advantages, 'from taking part in a con- versation? I take no pride in overcoming someone who may be right because he has not the competence to overcome me in language.'

He talked of peace and self-defence for some minutes. By the steps the first old man was struggling again with his note- book, trying to put another thought into words. 'What is the question?' demanded his Lordship. 'I'm finding it hard to love You at the moment.'

'Jesus . . . donkey . . . I . . .' stuttered the ancient.

'Our friend has a hazy reminiscence of something Jesus did, when he rode into Jerusalem, not on a warhorse but on a donkey: he told his disciples to go and they would find an ass,' said His Lordship. 'I'm sure' said Lord Soper, peering at the old man, 'that that donkey followed him as assiduously as you do me every Sunday.' `Isn't he clever? He's so clever', said the meek tramp beside me.

'I don't think,' said Lord Soper, moving onto capitalism, 'that Mrs Thatcher repre- sents absolute depravity: I think she is a characteristic of original sin.'

In between interruptions were long para- graphs of reflection: when they ended, the audience threw up potential topics.

'But what about the traffic problem?' asked another. 'You, my friend, could stay at home and that would be an improve- ment.' said Lord Soper.

'What about people living in cardboard boxes?'

'Not a bad idea, why don't you try it?' said Lord Soper. I looked at the meek man, but this time he made no comment.

'Are men equal?' another asked. Lord Soper said not, but as he did so a new figure strode into the crowd to applause, like a batsman coming to the wicket. He had a strong Italian-sounding accent: 'It's Mr Cornetto!' someone cried.

'It is rrritten in Genesis' Mr Cornetto reminded Lord Soper, 'that man is created in the image of God. We must all be equal.' Dr Soper did not seem to care for this much. Genesis is myth, he told him, and when had his questioner last read it?

'Quite rrrrecently,' said Mr Cornetto coolly, and to the astonishment of all pro- ceeded to quote it in the original. Lord Soper said he did not believe in the Old Testament. Did his questioner believe in the story of Adam and the rib? He did.

`You astonish me,' said Lord Soper.

'I may not understand how God went about it, but God can do it — He is almighty,' proclaimed Mr Cornetto (who turned out later to be a Mr Schehtman, an Argentine Israeli) in a voice loud enough to attract even more of the crowd, by this time around one hundred.

`God is not almighty', replied Lord Soper, 'if he can make as many mistakes as you have in five minutes. I haven't a picture of God. The picture I have of God is Jesus.'

Mr Cornetto was still trying to take this in. 'How can you believe in the immaculate conception?' he asked.

'I don't', said Lord Soper, triumphantly. 'I don't believe in the immaculate concep- tion. That attitude to the sexual back- ground of Jesus is unscientific, unhealthy and totally unnecessary. I believe you would be far better to find out what Christianity really means. I'm a pilgrim on a road, rather than a prospector with a map, and the best guidance on that road is goodness. I don't follow the Bible. The Bible is the servant of the Church.'

'In that case, why do millions follow the Bible?' roared Mr Cornetto. Lord Soper smiled. 'I'm afraid it's because so many people are stupid,' he said.

Previous page

Previous page