Dedicated modernists

Gavin Stamp

Architecture in an Age of Scepticism: A Practitioners' Anthology Compiled by Denys Lasdun (Heinemann £20)

A ll this talk about art is dangerous,'

Edwin Lutyens once said to Clough Williams-Ellis; 'it brings the ears so for- ward that they act as blinkers to the eyes.' Lutyens, of course, belonged to a genera- tion which, in that tiresomely English way, affected to be anti-intellectual; but on the few occasions he wrote about architecture . he expressed himself lucidly and illumina- tingly. Unfortunately, fashions for architects have changed. Today an architect feels obliged to pose as an intel- lectual even when he clearly is not. The result is embarrassing speeches and deeply Incomprehensible and pretentious justi- fications of very ordinary buildings.

This tendency to theorise and to verbal- ise rather than let buildings speak for themselves has emerged from the Modern Movement, which denied that architecture was only concerned with aesthetics. It had large-scale social and political aims, and these required exposition and formulation. The replanning of our cities and the re- housing of our people were carried through by sincere, blinkered men whose vision Was formed by a mass of theory and analysis. Alas, the resulting buildings and Conditions seemed to bear no relation to the bold ideas, so lengthily and turgidly expressed.

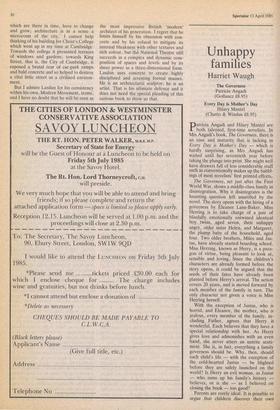

Architects' infatuation with ideas has much to do with the alienation of their Public. No longer is the intent of a designer evident in his buildings, so it must be explained. The Modern Movement arose O n a tirade of self-justification. Now, in retreat, in an 'Age of Scepticism' which Sir benys Lasdun rightly suspects is hostile to his profession, the Modern Movement needs even more self-justification. Hence this book. Its very title makes a statement: n is 'a practitioners' anthology'. Here are architects writing about their intentions and, by implication, this dismisses not only the critic but also the non-architect — the Public that has to live with the results of this most public of arts — as not competent to comment on what architects wish to create.

Of course it is interesting to know what architects think they are doing, but this is a Puzzling book, both because I cannot believe it will persuade any. layman and because I can detect no common theme or approach among the different contribu- tions. Their authors range from Continen- tal expressionists like Jorn Utzon, designer of the Sydney Opera House, and 'High Tech' whizz-kids like Norman Foster, who gives us an edited 'Project Diary' for his billion-dollar Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank, to Edward Cullinan, who writes something sensible which is worth reading. Cullinan is, quite rightly, one of the few architects singled out for praise by the Prince of Wales in his famous speech; he is a clever, idiosyncratic designer who is prepared to respect the past and work with traditional materials, as can be seen in his admirable rebuilding of the burned parish church at Barnes. I cannot see what he has in common with Foster, whose view of architecture is that of a child building with Meccano and who relies on engineers and electricity to solve problems. Yet for Lasdun 'the contributors are, I think, all individuals who are not unconge- nial to each other — Europeans who work in the tradition of the modern movement. They have all produced buildings full of eloquence and human depth.' This is to remove any useful meaning from the word 'modern'. I was struck the other day by the absurdity of a news report about an architect who had been elevated as chair- man of his firm, the Building Design Partnership. Readers were told he had worked on the new shopping centre at Ealing, a romantic extravaganza of brick gables and turrets, yet he was anxious to insist that he is still 'a dedicated mod- ernist'. Evidently today to be a 'modernist' is an article of faith rather than a commit- ment to any particular approach or style; the label is about as illuminating as 'Com- munist' for any ambitious Russian or 'C of E' for you and me.

Modernists of the old school there cer- tainly are in Sir Denys's compilation. There is Sir Leslie Martin on The De- velopment of a Theme' and it is a consis- tent theme, a theme which, in the heady 1960s, was going to sweep away almost all of Whitehall. Then there is James Stirling who, for me, betrays the compiler's belief that there 'seems to be a common voice here; a concern with a sense of time, place and people, and with the way space must be organised if architecture is to play its part in creating and maintaining the well- being of human society'. Tell that to Leicester University's Engineering Depart- ment, or to Queen's College, Oxford, or to the History Faculty of Cambridge, whose much vaunted library is now seriously proposed for demolition after a mere 17 years of very unsatisfactory life. Stirling is, however, living proof of the way in which Modern Movement ideology has protected architects from the public and from reality. When part of the Custom House collapsed owing to faulty foundations, its architect, David Laing, was forced to retire from practice and he died in penury. Stirling, in contrast, despite the failures of his build- ings, is applauded by his profession, given the Royal Gold Medal, described as a genius and goes from strength to strength.

But what really mars this introverted but nevertheless illuminating book is the inclu- sion of Alison and Peter Smithson, who represent the most arid and arrogant aspects of the Modern Movement. This husband-and-wife team have almost made egotism and self-obsession into an art form; certainly they provide a useful lesson in how to survive on a self-created reputa- tion and convince others of your seminal importance. Their real importance is as developers of architectural jargon, with the obsessive and pointless use of the three dots in the middle of a sentence . . . to impart greater significance or immediacy to banal statements. Here Mr and Mrs Smithson give us 'Thirty Years of Thoughts on the House and Housing,' without any hint that most of the projects discussed remained — mercifully — unexecuted and that one that was — Robin Hood Gardens in Poplar — is a brutal concrete complex of public housing which Thames Television viewers last year voted the worst example of post-war British architecture.

An architect who has also built little but is rather more humble is Christopher Alex- ander who two decades ago had the sense to realise that 'what I had learned at school, and the prevailing architectural wisdom, meant almost nothing . . . and that, fundamentally, and quite simply, we in our time just did not know how to build buildings'. (The punctuation here is used in the Smithsonian manner and does not mean that I have omitted part of the quotation.) Mr Alexander has therefore slowly learned how to build on a small scale and has considerable influence as a writer and teacher. Unfortunately, being American, he cannot help lapsing into pseudery. He illustrates a bedside table, 'made for love. I made it for Ingrid, one Saturday morning between nine in the morning and lunchtime . . . [the dots here indicate an excision] . . . I made the table without any idea in my mind that anyone would ever look at it except Ingrid — so I had literally no fear, no idea of what people would think, no desire at all to impress anyone, I only wanted her to like it.' So why does he tell us all about it?

And then there is Sir Denys Lasdun himself. It is unfortunate that this book should appear at a time when it is announced that the National Theatre is not only expensive to run but needs more money spent on it to keep out the rain, for Lasdun is a very serious and intelligent architect for whom I have great respect. He writes well and makes a strong case for a modern architecture which responds to,

and yet does not imitate, the past. His ideas on the nature of urban and interior

space are convincing, yet when he writes how he 'never separated [his] ideas about architects from those on the nature of cities which are there in time, have to change and grow; architecture is in a sense a microcosm of the city,' I cannot help thinking of his building for Christ's College which went up in my time at Cambridge. Towards the college it presented terraces of windows and gardens; towards King Street, that is, the City of Cambridge, it exposed a brutal rear of car-park ramps and bald concrete and so helped to destroy a vital little street as a civilised environ-

ment. •

But I admire Lasdun for his consistency within his own, Modern Movement, terms, and I have no doubt that he will be seen as the most impressive British 'modern' architect of his generation. I regret that he limits himself by his obsession with con- crete and by his refusal to mitigate its internal bleakness with other textures and rich colour, but the National Theatre still succeeds as a complex and dynamic com- position of spaces and levels and by its sheer power as a three-dimensional form. Lasdun uses concrete to create highly disciplined and arresting formal masses. He is an architectural sculptor; he is an artist. That is his ultimate defence and it does not need the special pleading of this curious book to show us that.

Previous page

Previous page