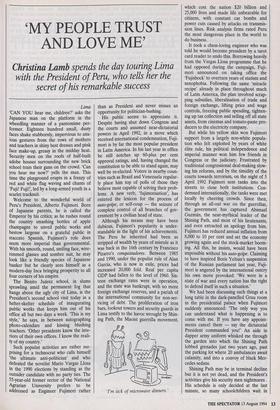

`MY PEOPLE TRUST AND LOVE ME'

Christina Lamb spends the day touring Lima

with the President of Peru, who tells her the secret of his remarkable success

Lima `CAN YOU hear me, children?' asks the Japanese man on the platform in the wheedling manner of a pantomime per- former. Eighteen hundred small, dusty faces shake stubbornly, impervious to anx- ious gestures from the rows of mothers and teachers in shiny best dresses and pink face make-up, greasy in the midday heat. Security men on the roofs of half-built adobe houses surrounding the new brick school train their guns on the crowd. 'Can you hear me now?' yells the man. This time the playground erupts in a frenzy of red and white flag waving and chants of `Fuji! Fuji!', led by a long-armed youth in a scarlet tracksuit.

Welcome to the wonderful world of Peru's President, Alberto Fujimori. Born of Japanese parents, he is called the Emperor by his critics; as he rushes round the country smashing bottles of apple champagne to unveil public works and bestow largesse on a grateful public in staccato Spanish, Fujimori's role does seem more imperial than governmental. With his smooth, round, smiling face, wire- rimmed glasses and sombre suit, he may look like a friendly species of Japanese banker but he clearly sees himself as a modern-day Inca bringing prosperity to all four corners of his empire.

The Benito Juarez school, in slums sprawling amid the permanent fog that hangs above the ugly city of Lima, is the President's second school visit today in a helter-skelter schedule of inaugurating public works that keeps him out of his office all but two days a week. 'This is my style,' he says, in between autographing photo-calendars and kissing blushing teachers. 'Other presidents know the inte- riors of their own offices. I know the reali- ty of my country.'

Such populist activities are rather sur- prising for a technocrat who calls himself `the ultimate anti-politician' and who defeated the novelist Mario Vargas Llosa in the 1990 elections by standing as the outsider candidate with no party ties. The 55-year-old former rector of the National Agrarian University prefers to be addressed as Engineer Fujimori rather than as President and never misses an opportunity for politician-bashing.

His public seems to appreciate it. Despite having shut down Congress and the courts and assumed near-dictatorial powers in April 1992, in a move which received international condemnation, Fuji- mori is by far the most popular president in Latin America. In his last year in office he still notches up 60-plus per cent approval ratings, and, having changed the constitution to be able to stand again, may well be re-elected. Voters in nearby coun- tries such as Brazil and Venezuela regular- ly place him top of polls of those they believe most capable of solving their prob- lems. A new verb, lujimorisation', has entered the lexicon for the process of auto-golpe, or self-coup — the seizure of complete control of all branches of gov- ernment by a civilian head of state.

Although his means may have been dubious, Fujimori's popularity is under- standable in the light of his achievements. The Peru he inherited had been as stripped of wealth by years of misrule as it was back in the 16th century by Francisco Pizarro's conquistadores. Between 1985 and 1990, under the populist rule of Alan Garcia, who is now in exile, prices had increased 20,000 fold. Real per capita GDP had fallen to the level of 1960. Six- teen exchange rates were in operation, and the state was bankrupt, with no more foreign exchange reserves, and a pariah of the international community for non-ser- vicing of debt. The proliferation of iron bars, lookout towers and security guards in Lima testify to the havoc wrought by Shin- ing Path, the Maoist guerrilla movement, `I'm sick of microwave dinners.' which cost the nation $20 billion and 25,000 lives and made life unbearable for citizens, with constant car bombs and power cuts caused by attacks on transmis- sion lines. Risk analysis firms rated Peru the most dangerous place in the world to do business.

It took a chess-loving engineer who was told he would become president by a tarot card reader to undo this. Borrowing heavily from the Vargas Llosa programme that he had opposed during the campaign, Fuji- mori announced on taking office the Tujishock' to overturn years of statism and xenophobia. Following the same 'miracle recipe' already in place throughout much of Latin America, the plan involved scrap- ping subsidies, liberalisation of trade and foreign exchange, lifting price and wage controls, freezing public spending, tighten- ing up tax collection and selling off all state assets, from cinemas and tomato-paste pro- ducers to the electricity company.

But while his yellow skin won Fujimori support from a largely non-white popula- tion who felt exploited by years of white elite rule, his political independence and imperial manner won him few friends in Congress or the judiciary. Frustrated by traditional congressional deal-making slow- ing his reforms, and by the timidity of the courts towards terrorism, on the night of 5 April 1992 Fujimori sent tanks into the streets to close both institutions. Con- demned internationally, the tanks were met locally by cheering crowds. Since then, through an all-out war on the guerrillas, the government has captured Abimael Guzman, the near-mythical leader of the Shining Path, and most of his lieutenants, and even extracted an apology from him. Fujimori has reduced annual inflation from 8,000 to 10 per cent and set the economy growing again and the stock-market boom- ing. All this, he insists, would have been impossible without his auto-golpe. Claiming to have inspired Boris Yeltsin's suspension of the Russian parliament last year, Fuji- mori is angered by the international outcry his own move provoked: 'We were in a state of war and every nation has the right to defend itself in such a situation.'

We had been discussing such things at a long table in the dark-panelled Grau room in the presidential palace when Fujimori suddenly announced: The only way you can understand what is happening is to come with me. If you have any appoint- ments cancel them — say the dictatorial President commanded you!' An aide in dapper army uniform whisked me through the garden into which the Shining Path lobbed grenades just two years ago, past the parking lot where 20 ambulances await calamity, and into a convoy of black Mer- cedes sedans.

Shining Path may be in terminal decline but it is not yet dead, and the President's activities give his security men nightmares . His schedule is only decided at the last minute, so many schoolchildren wait in vain in hot playgrounds for a presidential appearance. Inside the car Fujimori's pen is constantly at the ready to note down problems to enter into his Toshiba laptop later. 'I'm always looking for things which need doing because often it is little things that are at the root of big problems,' he says. 'But there is so much to do.' We both stare wordlessly at the endless line of mas- sive red and white support posts that were supposed to hold a monorail but were long ago abandoned by a previous government. As we drive through the streets of Lima, he rolls down the one-inch-thick bullet- proof glass and waves to the ambulantes, or street-walkers, selling plastic fruit refrig- erator magnets and executive toys strangely inappropriate wares for a country in which two-thirds of the population live below the poverty line. The ambulantes appear amazed and then delighted to recog- nise him and try to catch one of the photo- calendars he keeps in permanent supply. 'El Chinito!' (Little Chinaman) they shout as they try to grasp his hand. Others call 'El Hombre!' (the Man) to signal appreciation for their gutsy president. Tossing out calen- dars in fast succession, recruiting both myself and the driver to help, he smiles in delight. 'The names they call me show they trust and love me,' he says. I try to suppress a smile as one of the calendars hits a sheep grazing innocuously on a patch of grass. Fujimori is not surprised by the adula- tion. Jabbing his stubby finger at a slum on a hill, he says: 'That slum, San Cristobal, is fifty years old. It is right in front of the presidential palace yet it still does not have water or sewerage. That's what politi- cians do for you.' Perhaps reflecting his Japanese heritage, the key terms in Fujimori's vocabulary are efficiency and good management. A prag- matist free from the shackles of any ideolo- gy, he does not like to waste time and at the Peru-Japan school — our next step struggles not to look impatient while a padre sprinkles droplets from a plastic bot- tle labelled 'Holy Water' and two grubby children dance a clumsy marinero, a formal dance from the coastal regions. Fujimori makes no secret of the fact that he prefers soldiers to civilians. 'I like to get things done, to execute things, and that's why I like working with the military,' he says. He uses the army for everything from carrying out development projects to administering justice. As he announces gifts of computers, schoolbags and books to each school, it is a general who keeps tally in a notebook. The army is Fujimori's political party and his main adviser is Vladimir Montesinos, a cashiered captain know as Peru's Cardinal Richelieu and so shadowy that he has only twice been caught on film in the last decade. Having initially avoided the foreign press, Fujimori now welcomes them as her- alds for his message: 'My experience can be an example for the world. Various coun- tries can question democracy as we did in Peru. The most important thing is efficien- cy. Government has to be efficient or people suffer.' He told this to his fellow leaders at last month's Ibero-American summit in Carta- gena, who not surprisingly were unenthu- siastic. Fujimori didn't care: 'It's a new concept and a taboo theme, like that of the armed forces. But here in Peru it is I who controls the armed forces, which is not true in some other countries round here.' With these words he throws the last calendar out to an astonished-looking man at a bus stop. Next time it could be Mrs Susanna Fuji- mori who is hurling signed photo-calendars around the back streets of Lima. Last week the First Lady, a professed advisor of Mrs Hillary Clinton packed her bags and left her on grounds of 'political differences'. Mr Fujimori had inspired Congress to pass a law preventing the spouse of the presi- dent from running for the presidency her- self. The First Lady has other ideas, however. This is, after all, Peru.

Christina Lamb is a Nieman fellow at Harvard University.

Previous page

Previous page