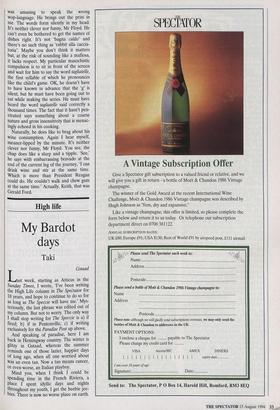

High life

My Bardot days

Taki

Gstaad Last week, starting as Atticus in the Sunday Times, I wrote, 'I've been writing the High Life column in The Spectator for 18 years, and hope to continue to do so for as long as The Speccie will have me.' Mys- teriously, the last phrase was edited out of my column. But not to worry. The only way I. shall stop writing for The Speccie is a) if fired; b) if in Pentonville; c) if writing exclusively for the Paradise Post up above. And speaking of paradise, here I am back in Hemingway country. The winter is glitzy in Gstaad, whereas the summer reminds one of those lazier, happier days of long ago, when all one worried about was an even tan. Now a tan means cancer, or even worse, an Italian playboy.

Mind you, when I think I could be spending time in the French Riviera, a place I spent idyllic days and nights throughout my youth, I get the heebie jee- hies. There is now no worse place on earth. I say this because it still has the remains of its once remarkable beauty, which only accentuates the present horror. I first began spending the summer months in Antibes in 1952, with my parents, and final- ly quit in 1977, one step ahead of the Arab hordes and Italian Mafia. A quarter of a century should be enough for anyone, no matter how spoilt, and although I am spoilt, I don't miss the place one bit. What I miss is my youth which I spent there.

I imagine that's what Brigitte Bardot misses, too, but she's much too self- obsessed to realise it. Bebe has been threatening to leave the place for exactly 26 years. I predict she will die there. (Not in the near future, I hope.) I know the exact date she first threatened to leave because I happened to be staying in her house, the famous 'La Madrague', during one of the worst summers of my life.

May of that year had started bad enough. The polo season in Paris had been can- celled because of the student revolt. The French powers that be showed no class in that one. When I reminded le baron de Nervo, the president of the polo club, that the Brits gave a ball on the eve of the Battle of Waterloo, he told me it was hardly comparable. My point was we should not only continue to play polo while the ludicrous so-called students put up barricades, we should also intensify the partying. For some reason I was out-voted.

Then my first wife left me a note saying that I was impossible to live with and that she would like a divorce. She added insult to my already bruised feelings by not asking for a red cent. That is when I flew to the south of France and drove to St Tropez. In no time at all, somebody had introduced me to Bebe and she had invited me to stay. My bad luck continued, however.

The trouble was that Brigitte wanted me near her in order to make her then hus- band, Gunter Sachs, jealous. She stood the same chance as La Ligne Maginot did against Guderian's panzers. Gunter had found a blonde Brunhilde, and now that he had become famous via Brigitte, was not looking back. La Bardot spent long hours into the night telling me about how awful life was. All I wished to do was to go out and have fun.

Brigitte had about 12 to 20 people stay- ing with her, and meals were taken en masse. Some of her entourage were truly appalling, others not too bad. In fact, after a while, I became very attracted to her sis- ter Mijanou, which added to the tensions in `La Madrague'. Brigitte, like most actress- es, was out of her depth. On one hand she was the best known and chased-after woman in Europe, on the other, a poor lit- tle rich girl dying for a strong man to take care of her. The trouble, however, was that only gigolos and opportunists came around. Good men were and are too proud to become Mr Bardot. I left her house one night leaving a thank you note behind, and we've never spoken since.

Previous page

Previous page