Television

Deep cover

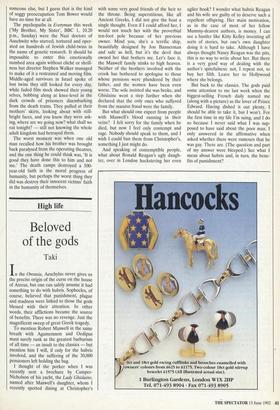

Martyn Harris

Tom Bower, our man in the Kremlin basement, was this week on the track of `illegals', the Soviet spies buried in deep cover throughout the West during the Cold War (Inside Story, BBC 1, 9.30 p.m., Wednesday). One of the great conscien- tious diggers of British journalism (Maxwell the Outsider, Klaus Barbie — Butcher of Lyons), Bower had unearthed a gallery of people who had spent most of their lives avoiding the attention of people like him- self.

Zalamon Litvin posed as a Finnish mer- chant in China, a Polish-Canadian student in California and finally a professor of poli- tics at USC, teaching, of all things, US con- stitutional law — all while running a spy network on the side. Ivan Jurkow and his wife had become first East Germans, then West Germans, then Brazilians and finally US residents, helping themselves to Ameri- can scientific secrets.

The most chilling thing about them was their total subordination of personal life. The Jurkows abandoned a four-year-old son in the USSR, while Jurkow himself spent nine months in India forging a 'cast- iron legend' of his previous 20 years. Zala- mon Litvin testified that 'I know I must get every detail of the legend, so that after six to eight months I believe I am that man, not Mr Litvin.' The Jurkows spoke nothing but German to each other for decades, even in bed, so that eventually they had forgotten their own native Russian.

Just how much these people mattered to the outcome of the Cold War is anybody's guess, since the actual secrets they pinched are still largely a matter of speculation. My own prejudice is that they didn't matter much: the Cold War was won by satellite surveillance and Coca-Cola ads.

Rival intelligence agencies prop each other up, each exaggerating the menace of the other, but then bailing each other out when things get nasty. The deep-cover Portland spy Gordon Lonsdale was sent down for 25 years amidst great hoopla and indignation, then quietly swapped after three years for Greville Wynne. William Fisher got 30 years for spying in America but was then exchanged for U2 pilot Gary Powers — all of which leaves the impres- sion sion of the thing being a bit of a boys game. What really interests me is the psy- chopathology of someone who can waste his entire time on earth pretending to be

someone else, but I guess that is the kind of soggy preoccupation Tom Bower would have no time for at all.

The psychopaths in Everyman this week (`My Brother, My Sister', BBC 1, 10.20 p.m., Sunday) were the Nazi doctors of Auschwitz who starved, tortured and oper- ated on hundreds of Jewish child-twins in the name of genetic research. It should be impossible to enter this emotionally numbed area again without cliché or shrill- ness but director Stephen Walker managed to make of it a restrained and moving film. Middle-aged survivors in Israel spoke of lost twins they still looked for every day, while faded film stock showed their young selves, bobbing along at knee-level in the dark crowds of prisoners disembarking from the death trains. They pulled at their mothers' skirts, looking about with still- bright faces, and you knew they were ask- ing, where are we going now? what shall we eat tonight? — still not knowing the whole adult kingdom had betrayed them.

The worst moment was when one old man recalled how his brother was brought back paralysed from the operating theatres, and the one thing he could think was, 'It is good they have done this to him and not me.' The death camps destroyed a 500- year-old faith in the moral progress of humanity, but perhaps the worst thing they did was destroy their innocent victims' faith in the humanity of themselves.

Previous page

Previous page