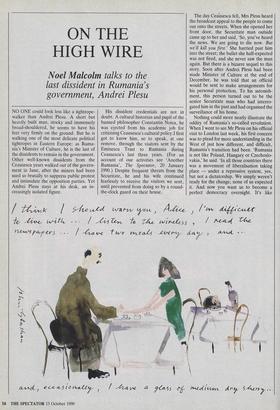

ON THE HIGH WIRE

Noel Malcolm talks to the

last dissident in Rumania's government, Andrei Plesu

NO ONE could look less like a tightrope- walker than Andrei Plesu. A short but heavily built man, stocky and immensely broad-shouldered, he seems to have his feet very firmly on the ground. But he is walking one of the most delicate political tightropes in Eastern Europe: as Ruma- nia's Minister of Culture, he is the last of the dissidents to remain in the government. Other well-known dissidents from the Ceausescu years walked out of the govern- ment in June, after the miners had been used so brutally to suppress public protest and intimidate the opposition parties. Yet Andrei Plesu stays at his desk, an in- creasingly isolated figure. His dissident credentials are not in doubt. A cultural historian and pupil of the banned philosopher Constantin Noica, he was ejected from his academic job for criticising Ceausescu's cultural policy.I first got to know him, so to speak, at one remove, through the visitors sent by the Eminescu Trust to Rumania during Ceausescu's last three years. (For an account of our activities see 'Another Rumania', The Spectator, 20 January 1990.) Despite frequent threats from the Securitate, he and his wife continued fearlessly to receive the visitors we sent, until prevented from doing so by a round- the-clock guard on their house. The day Cea'usescu fell, Mrs Plesu heard the broadcast appeal to the people to come out onto the streets. When she opened her front door, the Securitate man outside came up to her and said, 'So, you've heard the news. We are going to die now. But we'll kill you first.' She hurried past him into the street; the bullet she half-expected was not fired, and she never saw the man again. But there is a bizarre sequel to this story. Soon after Andrei Plesu had been made Minister of Culture at the end of December, he was told that an official would be sent to make arrangements for his personal protection. To his astonish- ment, this person turned out to be the senior Securitate man who had interro- gated him in the past and had organised the surveillance of his home.

Nothing could more neatly illustrate the oddity of Rumania's so-called revolution. When I went to see Mr Plesu on his official visit to London last week, his first concern was to plead for more understanding in the West of just how different, and difficult, Rumania's transition had been. 'Rumania is not like Poland, Hungary or Czechoslo- vakia,' he said. 'In all those countries there was a movement of liberalisation taking place — under a repressive system, yes, but not a dictatorship. We simply weren't ready for the change; none of us expected it. And now you want us to become a perfect democracy overnight. It's like wanting us to walk perfectly when we've been lying in bed with a crippling disease for 45 years.'

Yet some of this year's events in Ruma- nia, surely, suggest not the weak, faltering steps of an invalid but the well-aimed kick of a jackboot: what about the miners' rampage in June? `That was a terrible thing, of course. But people in the West misunderstand it. They think that was authoritarianism — no, on the contrary, that was a lack of power, a sort of weakness, an incapacity to solve things, and then the chaotic idea of bringing those people.' (That impersonal construction, `bringing those people', is a real tightrope- walker's phrase: officially, of course, the government still denies that it 'brought' the miners to Bucharest.) 'Besides, everyone talks about the miners, but nobody analy- ses the phenomenon of people in the streets of Bucharest applauding them. That is the more serious problem.' The international outcry which followed, • the cutting off of aid, the freezing of trade agreements and so on, have had some impact on the Rumanian authorities. Part of Andrei Plesu's message to the British Government was a plea for mercy. `If you say, "we shall not help you until you show you are a true democracy", you leave us in a vicious circle. We need your help in order to become more democratic. For a free press, for instance, we have the freedom but we lack the paper supplies and the printing technology. You should not stop helping a country just because you disagree with the person in power. You did the opposite before — it's strange. We were already fed up with Ceausescu by the early 1970s, and were amazed to see the West accepting him and helping him so much.' `But couldn't I turn your argument on its head?' I asked. 'Why not say the West made a terrible mistake by not trying to exert pressure on Ceausescu, and it must not make the same mistake again?' He smiled and lifted his hands. 'I'll just say this — God has two hands, the severe and the tender. Rigour must be tempered by love.' His deepest fear, he says, is of a kind of estrangement — polite on the surface, coldly indifferent underneath — between East and West. `I am afraid that the Iron Curtain will be replaced by a Velvet Curtain — a patronising smile, from a distance, with no real attempt to under- stand. The West will say, "Oh, they're all right now, they can manage by them- selves", and the East will say, "Well, the Western world is not as good as we thought: perhaps we needn't change so much from our old ways after all"'.

But does the present government in Rumania have the will to abandon the old ways? Doesn't it depend on the existence of all the old officials, administrators, police chiefs, directors of institutions, peo- ple who got their jobs through bribery and servility, and who voted for this govern- ment because they wanted it to preserve the system of power and privilege as it was? 'Of course the country is full of these people,' Andrei Plesu says. 'You can't just replace them overnight. In my ministry, I've sacked about 80 per cent of the staff. Ten days ago, Petre Roman [the Prime Minister] came to a meeting and said, "I have the feeling that in the ministries the old people are still there — can that be true? I'd like a list of them all, as soon as possible." You see, when people imagine that the government is subtly working to reinstate the communist system, they're quite wrong. It's much more a question of inexperience, of incompetence.' Maybe, I thought; but surely no government can be so inexperienced that it will actually seek to dismiss all its own supporters.

It's the same with the elections,' he says: `people claimed they were manipu- lated, but I can assure you that, unfortu- nately, they were not.' That `unfortunate- ly' looks like a dangerous wobble on the tightrope; but Mr Plesu deftly regains his balance. `I say "unfortunately" not because I think there was any other possibility. Everybody is saying now that the people were not clever enough to vote correctly. But how should they have voted? For the two old boys coming back to Rumania after so many years [the returning émigrés, Ion Ratiu and Radu Campeanu, who led the two main opposition parties]? It was not psychologically acceptable. So there was no real choice.'

Listening to those words on my tape recorder, I wish 1 had replied, 'Yes, and the reason why there was no real choice was that the people who should have come forward to lead the opposition parties did not do so, people from a younger genera- tion who had lived in Rumania and had gained a real moral authority by resisting the old regime — people like you.'

But instead I asked him this: `Do you feel compromised, contaminated even, by the position you have taken?' He smiled a weary smile. `I always knew it would be a compromising experience. The newspapers criticise me from both sides. The govern- ment still regards me as a foreign body, it doesn't really accept me. I feel I am losing my friends (not the closest ones, but the rest). I no longer have time to read books, to do my research. It is as if I am losing my identity altogether.' So why remain Minis- ter of Culture? 'I stay for just one reason: because if I go, somebody worse will take my place.'

Previous page

Previous page