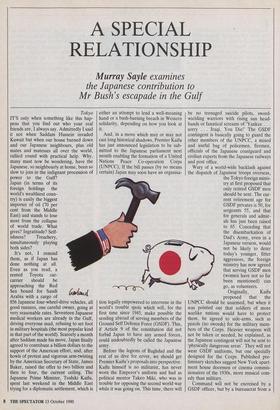

A SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP

Murray Sayle examines

the Japanese contribution to Mr Bush's escapade in the Gulf

Tokyo IT'S only when something like this hap- pens that you find out who your real friends are, I always say. Admittedly I said it not when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait but when our house burned down and our Japanese neighbours, plus old mates and matesses all over the world, rallied round with practical help. •Why, many must now be wondering, have the Japanese, so neighbourly at home, been so slow to join in the indignant procession of power to the Gulf? Japan (in terms of its foreign holdings the world's wealthiest coun- try) is easily the biggest importer of oil (70 per cent from the Middle East) and stands to lose most from the collapse of world trade. What gives? Ingratitude? Self- ishness? Treachery, simultaneously playing both sides?

It's not, I remind them, as if Japan has done nothing at all. Even as you read, a rented Toyota car- carrier should be approaching the Red Sea bound for Saudi Arabia with a cargo of 856 Japanese four-wheel-drive vehicles, all good runners, one careful owner, going at very reasonable rates. Seventeen Japanese medical workers are already in the Gulf, driving everyone mad, refusing to set foot in military hospitals (the most popular kind in that part of the world). Scarcely a month after Saddam made his move, Japan finally agreed to contribute a billion dollars to the support of the American effort, and, after howls of protest and vigorous arm-twisting by the American Secretary of State, James Baker, raised the offer to two billion and then to four, the current ceiling. The Japanese Prime Minister, Toshiki Kaifu, spent last weekend in the Middle East trying for a diplomatic settlement, which is either an attempt to lend a well-meaning hand or a bush-burning breach in Western solidarity, depending on how you look at it.

And, in a move which may or may not cast long historical shadows, Premier Kaifu has just announced legislation to be sub- mitted to the Japanese parliament next month enabling the formation of a United Nations Peace Co-operation Corps (UNPCC), If the bill passes (by no means certain) Japan may soon have an organisa- tion legally empowered to intervene in the world's trouble spots which will, for the first time since 1945, make possible the sending abroad of serving members of the Ground Self Defence Force (GSDF). This, if Article 9 of the constitution did not forbid Japan to have any armed forces, could undoubtedly be called the Japanese army.

Before the legions of Baghdad and the rest of us dive for cover, we should get Premier Kaifu's proposals into perspective. Kaifu himself is no militarist, has never worn the Emperor's uniform and had as political mentor Takeo Miki, who was in trouble for opposing the second world war while it was going on. This time, there will be no teenaged suicide pilots, sword- wielding warriors with rising sun head- bands or fanatical screams of 'Yankee . . . sorry . . . Iraqi, You Die!' The GSDF contingent is basically going to guard the other members of the UNPCC, a mixed and useful bag of policemen, firemen, officials of the Japanese coastguard and civilian experts from the Japanese railways and post office.

Wary of a world-wide backlash against the dispatch of Japanese troops overseas, the Tokyo foreign minis- try at first proposed that only retired GSDF men should be sent. The cur- rent retirement age for GSDF privates is 50, for sergeants 55, and that for generals and admir- als has just been raised to 65. Conceding that the disembarkation of Dad's Army, even in a Japanese version, would not be likely to deter today's younger, fitter aggressors, the foreign ministry has now agreed that serving GSDF men (women have not so far been mentioned) can go, as volunteers.

Originally, Kaifu proposed that the UNPCC should be unarmed, but when it was pointed out that soldiers of more warlike nations would have to protect them, he agreed to side-arms, such as pistols (no swords) for the military mem- bers of the Corps. Heavier weapons will not be taken or needed, he explained, as the Japanese contingent will not be sent to `physically dangerous areas'. They will not wear GSDF uniforms, but one specially designed for the Corps. Published pre- liminary sketches suggest New York apart- ment house doormen or cinema commis- sionaires of the 1930s, more musical com- edy than military.

Command will not be exercised by a GSDF officer, but by a bureaucrat from a new permanent secretariat `to be placed under the direct supervision and command of the prime minister'. The role of the Corps, as envisaged by Kaifu, is to 'moni- tor ceasefires or the holding of free elec- tions, to provide medical services as well as transportation, communications and admi- nistrative services'. Somewhere, by the sound of it, between Oxfam and the Royal Army Service Corps. Numbers? The GSDF has 13 divisions, about 120,000 men and 3,000 women, but the Maritime Self Defence Force (MSDF), or navy in coarser sailor's language, has only seven small troop-carrying ships with a total lift of 1,500. The contingent being discussed is more modest, 100 to 200, with a maximum of one platoon from the GSDF. They cannot travel by Japan Air- lines as the carrying of troops or weapons is forbidden by Article 86 of the Japan Civil Aviation Code. If the proposed law passes the parliament, whose upper house is controlled by a largely pacifist opposition, it is possible that UNPCC could set sail after the Emperor's enthronement in November, and even be in time to draw a Japanese line in the sand by Christmas.

Why bother? The Japanese contin- gent, outnumbered four to one by the press corps, is not likely to decide whatever Waterloo may be imminent, even should they, like Marshal Bliicher, manage to reach the field before it's all over. The thin-end-of-the-wedge theory, that the UNPCC is simply a ploy to get us used to Japanese troops going overseas with an eventual view to world conquest, is uncon- vincing, for reasons we shall see, although this reliable old stalking horse is sure to get another flogging. All that is left is for Japan to stand up, or rather rise microsco- pically from the prone position to be counted, the need for which has been brought home to Kaifu and his colleagues b. y a message in thunder from the Amer- ican right, left and centre that, as Senator Alfonse M. D'Amato (Republican) from New York puts it picturesquely, 'It's Time Japan Got Off US Gravy Train'. D'Amato's indictment expresses Amer- ican bitterness with a vehemence worth quoting. 'For 45 years', he writes, 'Amer- ican taxpayers have generously borne a financial burden totalling trillions of dol- larsto defend ourselves and our allies. Behind the shield of US military power, Japan rose from the ruins of World War II [Ah, but who caused them to? — MS] to become a global economic superpower. T. oday, America's young men and women in uniform stand guard in the Arabian desert against the military might and ruth- less ambition of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. United States forces are risking their lives in the Persian Gulf to defeat Saddam's aggression before Iraq — fat with stolen oil wealth and armed with chemical, biological and nuclear weapons — can turn on Israel and our other friends in the region . . . . `The Japanese government's assertion that it could spare only $1 billion to help finance the collective effort against Iraq was an affront to our servicemen and women, their families and all Amer- icans . . . . Hopefully, Japan's promises of an additional $3 billion for the Middle East effort represents only the first step toward a more serious commitment . . . . These allies [West Germany, offering a measly $2.2 billion, comes in for some stern D'Amato stick as well] have enjoyed gen- erations of peace and prosperity behind a defence shield provided in large part by American taxpayers. I believe that the time has come to tell our allies that there's no more free ride on the American gravy train.'

`How sharper than a serpent's tooth', as King Lear says, with that same tinge of indignant self-pity which makes him one of the Bard's less appealing heroes. There can, however, be little doubt that D'Ama- to speaks for many millions of Americans, even outside New York. The Japanese and the Germans have grown even fatter than the Iraqis, the American complaint goes, through the generosity of their Uncle Sam, largely by exploiting the ever-open Amer- ican market, and now that American boys (and girls) paid for by American taxpayers stand on the far-flung battle line, it is time for these spoilt brats of allies to return something to the hand that feeds and protects them. D'Amato's ominous '$3 billion . . is only a first step' suggests that no cheque, however massive, can ever clear this moral debt. Some Japanese pre-retirement boys, too, must stand on freedom's, or at least the free market's ramparts. Japan has no quick response that will mollify NYC. Hence the pistol- packin', Noel Cowardy UNPCC.

Needless to say, things do not seem quite so clear-cut in Tokyo. Two days after Saddam Hussein shook the world, George Bush telephoned Premier Kaifu to inform him that the United States was asking the UN for a blockade of Iraq. Bush had, of course, already called an 071 number before he dialled Tokyo's 03. What would be needed, he told the Japanese premier, was money, loadsamoney. Eager to please, Kaifu started to look.

Spectator readers have long been famil- iar with the Headless Monster theory which holds that no one is actually in charge in Japan. It is certainly true that the Japanese when they agree on something can also act with world-shaking speed and energy, but, when there is no consensus, can put practically anything off indefinite- ly. Certainly, they show no signs of taking up the British system whereby the Cabinet meets and quickly endorses what Mrs Thatcher is going to do. Yasuhiro Naka- sone, the prime minister before one, did indeed set up a Crisis Management Com- mittee of ministers and senior-bureaucrats, but Nakasone rather fancied the idea of barking orders from behind a large desk, which is one big reason why he is no longer prime minister. Kaifu did not convene the crisis committee but set about raising the wind the Japanese way, by patient, closed- door canvassing of the real people of power.

It did not, significantly enough, occur to anyone to suggest that the MSDF should be there. Japan has a 143-ship navy (the biggest, the 4,200-ton destroyer Hiei) in- cluding 50 highly competent minesweep- ers, constantly ready for sea. Japanese warships have been roaming the world for decades, attracting little attention and causing no trouble. I have, in fact, passed the time of day with some of these jolly Jack Taros in Piccadilly. It follows that no one really wants to see even token Japanese boys, aid workers, doctors or postmen in the Gulf. Let us get back to what everyone wants to see, Japanese money.

Advised by his foreign ministry to re- spond to Bush's call until the pips squeak, Kaifu had to persuade two much more powerful ministries, finance and interna- tional trade and industry, the fearsome MITI, to brass up. Finance (its Japanese name translates charmingly as the 'Big Treasure House Office') said that it was going to be, well, difficult. Although many Japanese corporations are fabulously weal- thy, the government itself is broke, saddled with a national debt of 164 trillion yen, or £672 billion (unmathematical readers will be comforted to hear that Japanese refer to these dizzying sums by terms invented by Buddhist monks to count the numbers of grains of sand in the universe).

This enormous debt, all owed to other Japanese, was run up in the past two decades in response to American demands that Japan stimulate its home economy. It absorbs 20 per cent of the budget in interest payments (Britain's national debt, which goes back to the Battle of the Boyne, takes 9 per cent). Kaifu's govern- ment was elected on, among others, a promise that he would end borrowing to cover the budget deficit by 1991. He is already struggling with resentment against the new 3 per cent consumption tax. The Big Treasure House informed Kaifu that the best Japan could do for Uncle without issuing more bonds was a billion dollars, and that even this would involve ratting on the development budget, which meant running the begging bowl past the flint- faced bureaucrats at MITI, representing the interests of Japanese industry to the government.

To MITI, the Middle East is bad news, the place where you have to buy oil at whatever price the bandits there are charg- ing this week. The Japanese-owned Ara- bian Oil Co, which was intended to be Japan's own Eighth Sister, has specialised in dry holes and deceitful sheikhs and has never been able to satisfy more than 5 per cent of the Japanese demand, the one notable failure in Japan's policy of buying up energy supplies at source.

MITI has vivid memories of what hap- pened during the first oil crisis of 1973, when tankers bound for Yokohama were diverted at sea to San Francisco, panic and inflation ran wild in Japan, and Japanese politicians rushed to the Middle East to promise mountains of money to the oil moguls. One of these deals, an oil refinery for Bandar Abbas in Iran, later renamed Bandar Khomeini and one day, who knows, to be Bandar Bush, cost Mitsui $8 billion, the loss mostly covered by MITI. MITI's advice to Kaifu was to smile sweet- ly and promise nothing.

In the event, the Japanese cabinet coolly opened its innings with a ban on importing oil from Iraq, a ban on exports to Iraq and Kuwait, the suspension of loans and invest- ments, and the freezing of economic assist- ance to Iraq. In practical terms, all this meant was that Japan was not, single- handed, going to run the international blockade. At first MITI wanted the sanc- tions to apply only to future contracts, pleading that the honour of Japanese gentlemen required existing ones to be carried out. Tightening the screw a fraction more, Tokyo informed Baghdad that Sad- dam Hussein's invitation to the enthrone- ment of Emperor Akihito in November would be cancelled unless they got out of Kuwait. This has, so far, produced no result.

Meanwhile, Foreign Minister Taro Nakayama pointedly refrained from join- ing the common herd of politicians busy killing Saddam with their mouths, and instead visited the Middle East in person in search of a peaceful solution. Premier Kaifu himself was in Jordan last week talking to Iraqi biggies. When all else had failed, Japan promised Washington its first billion. George Twist was quickly on the line again. The offer was raised to two billion, and after another phone call (let us hope for the sake of future historians that some secretary handier with a tape recor- der than Richard Nixon's Rosemary Woods is logging all these calls) finally to four billion, six weeks after Kuwait was brusquely dealt out of the game. Crestfal- leq, the empty Big Treasure House has had 'We'd like a truly memorable meal to tide us over a possibly forgettable evening in the

theatre.'

to go back to peddling bonds.

Even then, all is not going merry as a wedding bell between the odd couple of the Pacific. Japan's first two billion is supposed to go direct to the US forces in the Gulf, the next two in the form of low-interest loans to Egypt, Turkey and Jordan. The Americans want all the che- ques sent straight to Washington, a.s.a.p. Finance Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto has asked for an itemised invoice on behalf of his ministry (Waiter! Could we check that bill?') and proposes that the second two billion should go through the World Bank, or some such international stakeholder. The Japanese fear that the Americans are trying to establish a pipeline to the Big Treasure House, with the tap in Washing- ton, and who can say they are being paranoid?

Next, the US House of Representatives has called on the Japanese to pay the full cost of maintaining 35,000 US troops in Japan, $4.6 billion a year, instead of half as much, at present. The resolution calls for 5,000 to be withdrawn until such time as the Japanese cough up. To which the Japanese Defence Minister Yozo Ishikawa has retorted that 'the US Congress lacks common sense. Japan has never asked for the stationing of US troops here. We should say, let them go home.'

Now, in our role as marriage counsel- lors we are getting down to the real cause of the conflict. The world in fact faces not one, but two crises, closely linked. The United States economy is, practically speaking, bankrupt and so, therefore, is the global economic system which it over- shadows.

Even as Bush was rattling his cup around the world, the US government was totter- ing towards bankruptcy. The US budget deficit is already over $241.7 billion for the first 11 months of the current financial year, a record that beats even Ron Reagan's wildest profligacy. And Japan is, of course, closely involved in this second crisis, too — but as a benefactor, the only solvent one left.

Ishikawa is quite right. The Japanese did not invite the United States to station its boys here. Despite much nauseating talk of `traditional friendship', Japan and the US did not fight shoulder to shoulder in the second world war, Korea and Vietnam. Defeated Japan did not accept an Amer- ican garrison simply, or even mainly, out of fear of the Russians or communism, but as the price of getting rid of an American occupation that was supposed to last for 50 to 100 years. American taxpayers did not `generously' pay for the defence of Japan (or West Germany, for that matter). The Americans chose, if they had to fight the Soviet Union and China, to do so in or near Japan rather than in or near Los Angeles, an understandable if less saintly preference. The US/Japan relationship be- gan, in short, as a by-product of the Cold War. Now the Cold War is, we are told, over, although Senator D'Amato seems not to have noticed, and with it the old Japanese/American marriage of conveni- ence is dead.

But over the last decade the relationship has found a new basis, although the rhetor- ic of both sides has been slow to catch up. In the 1950s the Americans opened their market to Japanese manufacturers to save their defeated enemies from dangerous communism. Protégé of the strongest naval power (as they had been of Britain, 1902- 1923, Japan's earlier wonder years), the industrious islanders soon found a new role as the workshop and banker of the world, rather like Britain's in the last century except that the USN played, and plays, the role of Queen Victoria's RN. The Japanese have been able to make a meal of what they are good at — working hard, sharpen- ing their skills, saving money — and avoid what in 1,600 years they have always managed to avoid — their own military, grown strong, setting up an onerous dicta- torship. The new relationship really blossomed in America's lotus-gorging Reagan years, with the Japanese providing the lotuses by lending their savings to Americans so that they could buy ever more Japanese gadgets. Under the carrot and stick of MITI, Japanese industry has pursued a strict energy policy, and Japan produces the same unit of GNP for 20 per cent less oil than it did in 1973 (the United States, with no energy policy at all, needs 10 per cent more). Japan has 144 days' oil in reserve (50 days in 1973) and may be unobtrusively feeding reserves into the domestic system now. Certainly, Japanese petrol prices have scarcely moved in recent weeks and there is no sign of panic buying by Japanese consumers. MITI's advice to Kaifu, to play the crisis cool and promise as little as possible, has 17 years of careful spadework behind it. Bush's importunacy has, as far as we can see, none. Japan last year exported $180 billion of capital, the bald eagle's share to the United States. For a decade, capital imports, mainly from Japan and West Germany, have enabled Americans to live it up to $150 billion dollars a year above their productive capacity, wallowing in the world's cheapest oil and other energy (half the Japanese price.) To be a net capital exporter, you need a reliable current account surplus, or in pauper's English, if you don't rake it in, you can't lend it out. Only two of the world's economies have a big, reliable surplus, and Germany's is mortgaged to its destitute relatives. Japan is now the only net source of capital left, a one-nation Opec of money. The world capitalist or trading system, which even people like Pol Pot and Kim II Sung now seem eager to join, needs capital as much as it needs oil, possibly more so. We need Kaifu, in short, even more than we need Saddam.

This immediately suggests a new basis for the Pacific partnership, nothing less than a Nipponese-American world con- dominium. The same thought has occurred to Shintaro Ishihara, Japan's answer to Jeffrey Archer. An author of kimono- tugging novels turned politician in the conservative interest, Ishihara is scarcely another Edmund Burke, but he speaks for many Japanese in the proposal, aimed directly at America's heart, that he pub- lishes in the current Playboy magazine. `America and Japan could, working together, make a new civilisation for the entire world — we are a very strong tractor-and-engine combination,' writes Ishihara, already well-known in the United States as co-author of The Japan That Can Say 'No', a repudiation of the old master- and-servant relationship. 'There is no need for Japan to overtake the US as number one. It is better to be a powerful number two, not to try to gain hegemony through economics.'

This is seductive talk. America cannot save, Japan alone cannot protect its global business interests. While it may not exactly 'I've seen it for myself, Tibley. That yucca in your office is pot-bound.' be the brave new system the Soviet Foreign Minister has in mind, a world run by the firm of Rambo and Scrooge Inc. has a certain attraction, especially for the part- ners. But we all know those partnerships in which the parties cover for each other's weaknesses. They tend to lack mutual respect, and the couple winds up communi- cating by notes stuck on the refrigerator door. Japanese in body bags, Americans in credit — sooner or later, each is likely to demand what the other cannot bring itself to supply, and recriminations have started already.

Meanwhile South Korea, the only nation American taxpayers have so far successful- ly defended (exports $90 billion last year), has announced the donation of a careful $220 million to the Gulf effort. No Korean boys are to be sent. 'Blow, blow, thou winter wind, as Amiens sings in As You Like It, 'thou art not so unkind as man's ingratitude.' And he was not even thinking of tight-fisted, unco-operative eastern man.

Previous page

Previous page