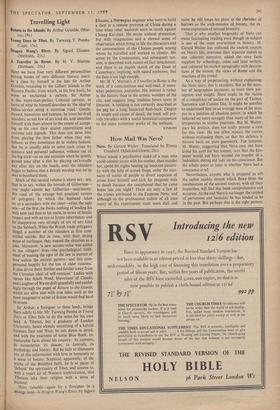

How Mad Was Nero?

Nero. By Gerard Walter. Translated by Emma Craufurd. (Allen and Unwin, 25s.)

WHAT would a psychiatrist make of a man who could commit incest with his mother, then murder her, spend his nights beating up innocent passers- by with the help of armed thugs, order the mas- sacre of scores of people to divert suspicion of arson from himself and kick his pregnant wife to death because she complained that he came home late one night? These are only a few of the crimes attributed to the Emperor Nero, and although to the professional sadists of all time many of his experiments must seem dull and

naive he still keeps his place in the chamber of horrors as the arch-monster of history, the ex- treme expression of sensual brutality.

That is why another biography of Nero can make fascinating reading even though its subject is one of the most overwritten in history. M. Gerard Walter has collected the ancient sources on Nero's life, rewritten their separate stories as one coherent narrative, added the stray facts supplied by achwology, coins and later writers, and coloured his starker paragraphs with descrip- tions of the season, the views of Rome and the reactions of the crowd.

As a way of perpetuating, without explaining, the Nero story, this is excellent. But as the num- ber of biographies increases, so must their per- ception and insight. Nero might be the victim of a conspiracy of malice on the part of Tacitus, Suetonius and Cassius Dio. It might be possible to understand him as an average man of his time, put in a position of absolute power, in which he behaved no more savagely than many of his con- temporaries in similar positions. But M. Walter, pace his preface, does not really present a case for this view. He too often repeats the stories without evaluating them, so that his defence is thrown back on pure guesswork. For instance, M. Walter, suggesting that Nero may not have killed his aunt for her money, says that the Em- peror would not have wanted the murder of a bedridden, doting old lady on his conscience. But the whole point at issue is whether Nero had a conscience at all.

Nevertheless, anyone who is prepared to sift the rather muddy stream which flows from the combination of the ancient sources, with all their impurities, will find this book comprehensive and accurate. At the end Nero is no longer the symbol of perversion and bestiality he has tended to be in the past. But perhaps that is the right picture;

a doctor, not a historian, may be needed to ex- plain him. Or perhaps he was a sane, pathetically weak, cowardly and inadequate man, caricatured by lurid stories and senationalist gossip-writers. M. Walter's book is a little too tentative and balanced to swing the verdict over to the second view, but it contains enough evidence to justify a jury in saying, 'Not proven' to the first.

Nero was not mad, says M. Walter, and when he enters Nero's mind he imagines him thinking with the cool logic of a professor of ancient history. But between madness and cold-sober sanity there is a scale with many degrees of irrationality, and somewhere on this scale lies Nero. He moved further along it as his reign went on; he never felt the need to act consistently because none of the pressures that make men consistent applied to the Emperor of Rome. That is the clue to his character. Nero was no more of a psychopath than many so-called 'normal,' ordinary people. But he was a living demonstra- tion of what can happen to such people if all social, moral, economic, • and political restraints are removed. Nor was he the last of his kind.

KENNETH CAVANDER

Previous page

Previous page