SOME CHANCE FOR A CHANCELLOR

A. L. Rowse surveys the

history of suitable and awkward Oxford officers

THE Chancellorship of Oxford University, though highly decorative, is no mere ornamental office, though it has tended to become less potent and more ornamental as time has gone on. Its origin goes right back to the beginnings of the university about the time of Magna Carta (1215).

At first the Chancellor was appointed from among the Masters of Arts by the Bishop of Lincoln, in whose diocese Ox- ford lay and who held chief authority over the nascent university. The Chancellor represented him within the walls, while at the same time coming to represent the university and its interests.

So it went all through the Middle Ages. The university was almost entirely clerical, and so were the Chancellors. By the end of the Middle Ages they had become gran- dees, bishops and archbishops themselves — like Cardinal Morton, Henry VII's right-hand man, and Archbishop Warham, Chancellor from 1506 till his death in 1532.

The Reformation changed all that. Henceforth the Chancellors were almost always laymen, beginning with Sir John Mason of All Souls and a Secretary of State. Under Mary's reaction Cardinal Pole was Chancellor for a couple of years, but with Elizabeth I's accession Mason was restored. He was succeeded by the Queen's prime favourite, Leicester, a much misunderstood man. He was a good servant of the state, and made a conscien- tious Chancellor for 20 years, 1564-85, taking an active part in the university's affairs and looking after its interests at Court. In his time he usually nominated the Vice-Chancellor, who was customarily a cleric. For all his colourful sex life, he was regrettably a patron of Puritans. True, he occasionally got pickings out of the university, but that was all in the day's work in Elizabethan times. He was succeeded briefly by Sir Christ- opher Hatton, another of the Queen's favourites, but happily a good Anglican. The emphasis throughout this period was to increase authority, particularly that of the heads of colleges, and keep order in the nursery — as against mediaeval democracy and disorder, student riots and demonstra- tions, etc. After all, they were only a lot of boys.

We see William, Earl of Pembroke, today in the fine bronze statue by Le Sueur outside the entrance to the Bodleian. But the greatest benefactor among Chancellors was once more a cleric, Archbishop Laud, 1630-41. He collected and gave to the Bodleian some 1,500 rare manuscripts, mostly from the Middle East, which gave Oxford the lead in Oriental studies for the next century. Disciplinarian and reformer, he laid down the rota by which Vice- Chancellors succeeded to office practically up to our time. He built the lovely Canter- bury quadrangle at St John's. Oxford was always nearest the heart of poor Laud, killed by the beastly (and Philistine) Puri- tans.

When they won the Civil War they had made, Oliver Cromwell was foisted on us as Chancellor — a Cambridge man to boot! There followed briefly his son Richard, `Tumbledown Dick' — MP for Cambridge University. He didn't last long, and with the Restoration of the King things resumed their proper course. Clarendon, who had kept belief in the nation returning to its senses all through the years of exile, became Chancellor, 1660-7. He was a benefactor too — witness the Clarendon Building and the later Clarendon Laboratories.

Oxford's loyalty to the Stuart cause was represented for the next half-century by the reign of two dukes of Ormonde, 1669-1715. When the second duke went into exile for the cause, he was succeeded by a couple of Jacobite Chancellors, who held office sulkily right through the reigns of the first two Hanoverian Georges, who naturally favoured Cambridge.

It must have been at this time that Oxford won for itself the title, 'Home of Lost Causes', for it went on being domi- nantly Jacobite right up to the accession of George III, who at least spoke English. A leading figure was the celebrated orator, Dr William King. At a speech of his in the Sheldonian in 1749 — only four years after the '45 Rebellion — he repeated the word redeat six times: 'May he come back,' meaning the Young Pretender, Charles Stuart. Every time, King paused for a thunder of applause.

All this was very childish, of course, in academic fashion — like voting down a Prime Minister for an honorary degree. And when Dr King next year met the Young Pretender on his clandestine visit to London, he was rather disillusioned.

The great William Pitt, a Trinity man, was however so put out by Oxford's silly Jacobitism that he sent his clever son, the Younger Pitt, to grander Trinity at insalub- rious Cambridge. We might say that, with George III, Oxford reconciled itself to the Hanoverians, as indeed Dr Johnson did, in spite of lingering Jacobite sentiments. George III's favourite Prime Minister, Lord North, was Chancellor for 20 years.

A couple of Whig worthies followed him — a Duke of Portland and Lord Grenville, who sat out all the years in the Chancellor's chair right up to 1834. Then a great notability took on, the Duke of Welling- ton, rather reluctantly because his Latin was rusty. However, having faced Napo- leon at Waterloo, he found the courage to face the dons with his false quantities, Jacobus, Carolus, etc.

After him came the Lord Derby, who was not only another Prime Minister but a first-rate classical scholar, translator of the Iliad. He ruled from 1852 to 1869, to be succeeded by another intellectual, the great Lord Salisbury, an All Souls man. Yet another came along in Lord Curzon, whom I am old enough to remember pontificating and stepping out in full panoply.

Then came a deplorable bump. After Curzon's death, Asquith was the most eminent Oxford man available and should have been elected Chancellor; but the Tories wouldn't have him. Asquith said agreeably that some people wouldn't vote for him because he was a bachelor (he had never taken his MA), others because he wasn't a bachelor (i.e. on account of Margot). So the Tories forked in a second- rater, a Lord Chancellor called Cave who has heard of him?

Edward Grey, who followed in 1928, was an altogether nobler figure. The joke about him as Chancellor was that, as an undergraduate at Balliol, he had been sent down for 'incorrigible idleness'. Jowett, that sharp talent-spotter, saw that young Grey had latent ability, but not even Jowett could make him work.

Warden Pember at that election asked me, as a junior Fellow, whom I fancied. Though a Labour man, I was always churchy, and I replied 'Archbishop Lang' (good college spirit too, for he was an All Souls man). Warden Pember, who was an old-fashioned Whig, wouldn't hear of it. He was against 'the divine right of presby- ters', he said. Perhaps more important, Edward Grey was an old friend. He got it.

But he was succeeded by an All Souls man, and one who could not be more churchy, Lord Halifax. He made a magnifi- cent figure with all that height (he had difficulty in getting a bed to fit him in College), and that long aristocratic counte- nance, with the sad expression, depicted in Oswald Birley's portrait of him in our hall. Finally, Harold Macmillan, plump, middle-class (Etonian veneer), euphoric, bouncy; half-American, quarter-Scots crofter — he was not all that met the eye.

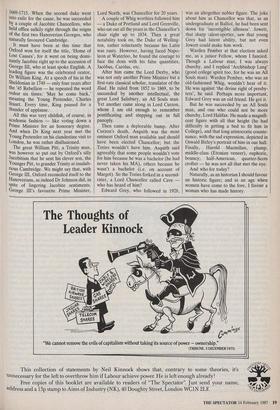

And who for today?

Naturally, as an historian I should favour an historic figure; and in an age when women have come to the fore, I favour a woman who has made history.

Previous page

Previous page