CHESS

Mad Max

Raymond Keene

IN SOME tournaments nothing will go right. I arrived at the 1970 British Champ- ionship hoping to win it but instead drew game after game. In the final round I faced the dangerous Australian master Max Fuller and I had to win in order to share second place. Even after one of the most violent games of my life, before or since, this should still have ended as a draw if Fuller had found the concealed resource on move 23!

Fuller-Keene; British Championship 1970; Tartakower Defence

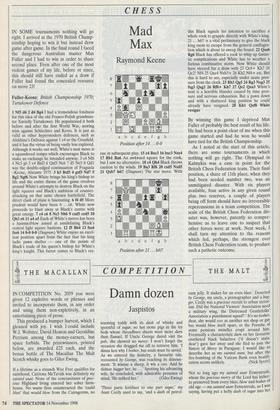

1 Nf3 d6 2 d4 Bg4 I had a tremendous fondness for this idea of the old Franco-Polish grandmas- ter Xavielly Tartakower. He popularised it both before and after the first World War, scoring wins against Schlechter and Keres. It is just as valid as other hypermodern defences, such as Alekhine's Defence against 1 e4 or the Grunfeld, and it has the virtue of being vastly less explored. Although it works out well, White's next move is a squandered tempo which encourages Black to make an exchange he intended anyway. 3 c4 Nf6 4 Nc3 g6 5 e4 13xf3 6 Qief3 Nc6 7 d5 Ne5 8 Qdl was the double-edged continuation of Fraguela –Keene, Alicante 1975. 3 h3 Bxf3 4 gxf3 Nd7 5 Bg2 Ngf6 Now White brings his king's bishop to life and the entire theme of the game revolves around White's attempts to destroy Black on the light squares and Black's ambition of counter- attacking on that same chosen battlefield. The direct clash of plans is fascinating. 6 f4 d5 More prudent would have been 6 ... c6. White now proceeds to blast away at Black's centre with great energy. 7 c4 c6 8 Nc3 Nb6 9 cxd5 cxd5 10 Qb3 e6 11 a4 a5 Each of White's moves has been a hammerblow aimed at annihilating Black's central light square bastions. 12 f5 Bb4 13 fxe6 fxe6 14 0-0 0-0 (Diagram) White enjoys an excel- lent position apart from the fact that his king lacks pawn shelter — one of the points of Black's trade of his queen's bishop for White's king's knight. This factor comes to Black's res-

Position after 14 . . . 0-0 cue in subsequent play. 15 e4 Bxc3 16 bxc3 Nxe4 17 Rbl Ra6 An awkward square for the rook, but I saw no alternative. 18 c4 Qh4 Black throws caution to the winds. 19 Ba3 Rf6 20 cxd5 NxdS 21 Qxb7 h6!! (Diagram) The star move. With Position after 21 . . . h6!!

this Black signals his intention to sacrifice a whole rook to grapple directly with White's king. 21 ... h6!! is a vital preliminary to give the black king room to escape from the general conflagra- tion which is about to sweep the board. 22 Qxa6 Rg6 Black has offered a rook to whip up fantas- tic complications and White has to weather a furious combinative storm. Now White should have steered for a draw with 23 Qc8+ Kh7 24 Qc2! Nf4 25 Qxe4 Nxh3+ 26 Kh2 Nf4+ etc. But this is hard to see, especially under acute pres- sure from the clock. 23 Rb3 Qg5 24 Rg3 Nxg3 25 fxg3 Qxg3 26 R18+ Kh7 27 Qe2 Qxa3 White's next is a horrible blunder caused by time pres- sure and nervous exhaustion. But a pawn down and with a shattered king position he could already have resigned. 28 Khl QxfS White resigns

By winning this game I deprived Max Fuller of probably the best result of his life. He had been a point clear of me when this game started and had he won he would have tied for the British Championship. As I noted at the start of this article, there are some tournaments in which nothing will go right. The Olympiad in Kalmykia was a case in point for the British Chess Federation team. Their final position, a share of 11th place, when they had been seeded number two, was an unmitigated disaster. With six players available, four active in any given round plus two reserves, a couple of players being off form should have no irreversible repercussions in a team competition. The scale of the British Chess Federation dis- aster was, however, patently so compre- hensive as to leave one to suspect that other forces were at work. Next week, I shall turn my attention to the reasons which led, perhaps, the strongest ever British Chess Federation team, to produce such a pathetic outcome.

Previous page

Previous page