0 ver the largest room in the Art Nou- veau

exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum there beetles a complete Parisian Metro station entrance by Hector Guimard. To beetle — that is, to hang threateningly, of fate, brows, cliffs, etc. — is the mot juste in more than one way, since Guimard's lamps, lit a vivid red, are remarkably like the eyes of giant insects. But, then again, they could be flowers of a menacing variety, Venus Flytraps, say. The ambiguity is typical of Art Nouveau. Elsewhere in the exhibition there are cases of zoomorphic and plantiform jewellery and glassware. There are bracelets and brooches, in the form of serpents, orchids, insects, hornets, damselflies, irises — sometimes it is hard to tell which is which. Similarly, it can be hard to tell the bats from the flowers and sea creatures on the glassware, no matter whether it is from Paris, New York, Nancy or Budapest. The Art Nouveau was a universal, inter- national style, which spread from Moscow to Chicago, which may explain why this is such an enormous exhibition. It has spread through the first large room — big enough for some entire shows at the V&A — before it has dealt exhaustively with just the sources of Art Nouveau: Japanese art, Islamic art, Rococo, arts and crafts, etc. Only then does it get down to the stuff itself, by theme — the obsession with nature and evolution, for example, from Which the above examples are taken — and the various centres: Paris, Brussels, Glas- gow, Vienna, Helsinki and so on.

On and on it goes, a feast of Art Nou- veau, for those who like it. And an awful lot of people do, to judge by the crowding on the afternoon on which I went along (tickets are by time-slot). I suspect that the V&A are on to a winner here.

The reason for this popularity is not hard to find. Where 20th-century design has been by and large austere and visually self-deny- 1.11g, Art Nouveau was exuberant, excessive, indulgent (all popular qualities, in art and elsewhere). Modernism has tended to believe, along with Adolf Loos, that orna- ment is crime. The Art Nouveau — though in many ways it led on to modernism, as one can see, say, from the spare metal work of the Vienna Secession — tended to think You couldn't have enough decoration, and the more bizarre the better. Partly that was because of a fin de siècle propensity to lie back and float away on all those fronds and undulating tresses of hair — which no doubt explains the hippy fascination with the style. (An aged modernist with whom I once went round a Gaudi building remarked, 'That is not architecture, it is marijuana.') But there was also a belief, derived from the Symbol-

Exuberant,

•

excessive, indulgent

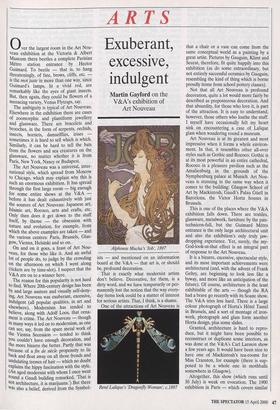

Martin Gayford on the V&A's exhibition of Art Nouveau Alphonse Mucha's ;lob', 1897 ists — and mentioned on an information board at the V&A — that art is, or should be, profound decoration.

That is exactly what modernist artists don't believe. Decorative, for them, is a dirty word, and we have temporarily or per- manently lost the notion that the way every- day items look could be a matter of interest for serious artists. That, I think, is a shame.

One of the attractions of Art Nouveau is Rene Lalique's 'Dragonfly Woman', c.1897 that a chair or a vase can come from the same conceptual world as a painting by a great artist. Pictures by Gauguin, Klimt and Seurat, therefore, fit quite happily into this exhibition (as do some extraordinary, but not entirely successful ceramics by Gauguin, resembling the kind of thing which is borne proudly home from school pottery classes).

Not that all Art Nouveau is profound decoration, quite a lot would more fairly be described as preposterous decoration. And that absurdity, for those who love it, is part of the attraction. It is easy to understand, however, those others who loathe the stuff. I myself have occasionally felt my heart sink on encountering a case of Lalique glass when wandering round a museum.

Art Nouveau is at its greatest and most impressive when it forms a whole environ- ment. In that, it resembles other all-over styles such as Gothic and Rococo. Gothic is at its most powerful in an entire cathedral, Rococo in a pleasure pavilion such as the Amalienburg in the grounds of the Nymphenburg palace at Munich. Art Nou- veau is stunning in the same way when it comes to the building: Glasgow School of Art by Mackintosh, Gaudi's Palau Gael' in Barcelona, the Victor Horta houses in Brussels.

This is one of the places where the V&A exhibition falls down. There are textiles, glassware, metalwork, furniture by the pan- technicon-full, but the Guirnard Metro entrance is the only large architectural unit and also the exhibition's only truly jaw- dropping experience. Yet, surely, the my- God-look-at-that effect is an integral part of response to the Art Nouveau.

It is a bizarre, excessive, spectacular style, and its most important achievements were architectural (and, with the advent of Frank Gehry, are beginning to look less like a byway, and more like an anticipation of the future). Of course, architecture is the least exhibitable of the arts — though the RA had a brave go recently with its Soane show. The V&A tries less hard. There is a large colour photograph of Horta's Hotel Tassel in Brussels, and a sort of montage of iron- work, photograph and glass form another Horta design, plus some slides.

Granted, architecture is hard to repro- duce, but it might have been possible to reconstruct or duplicate some interiors, as was done at the V&A's Carl Larsson show a few years ago. It would have been nice to have one of Mackintosh's tea-rooms for Miss Cranston, for example (there is sup- posed to be a whole one in mothballs somewhere in Glasgow).

Altogether, this show (which runs until 30 July) is weak on evocation. The 1900 exhibition in Paris — which covers similar ground — does imaginative things with lighting and design in rooms which are quite as unpromising as those at the V&A. In South Ken the design is straightforward, functional and rather ugly. The result is a heavily didactic show which focuses largely on the more exhibitable decorative arts. Nonetheless, it is well worth seeing, and certain to be thronging with people.

The exhibition programme at the V&A has been sporadic and up and down for more than a decade. This is an up, but still the V&A has seldom ventured out of the 19th century — William Morris, Larsson, Pugin — in terms of big shows. The muse- um's remit is much bigger than that: sculp- ture, non-European art, the baroque, the 18th century. However, I am pleased to see a mediaeval show and a Renaissance sculp- ture show coming up in the next few years. Things may be improving on Exhibition Road.

Previous page

Previous page