THE CITY'S BEST MODERN BUILDING

Gavin Stamp on

the threat to Bracken House

THE last living survival of mediaeval London is passing. As is too well known, `Fleet Street' is going. Newspaper offices and printing works are leaving their tradi- tional homes and migrating to outlandish parts of the city — to Docklands, Kensing- ton High Street, Battersea — and with this move disappears that intricate, untidy and overcrowded fusion of industry, commerce and everyday life, so hated by planners and traffic engineers, which used to character- ise London and which is still to be found in the cities of the East. Efficiency, in theory, will now govern the newspaper industry, but the loss of the old methods will be felt not only by journalists deprived of a congenial and lively environment.

The London division of English Heritage — that noble survivor from the GLC — has realised the historical importance of what has survived in and around Fleet Street and has been busy recording the interiors of the buildings before the presses fall silent. Much, like Carmelite House — a pioneer purpose-built newspaper works — is of purely archaeological and historical in-

terest. From an architectural point of view, the wonder of Fleet Street is its varied and traditional urban character, created by many different buildings on ancient, nar- row frontages with an intricate network of alleys behind. This is very precious but much will go as Fleet Street is inevitably redeveloped for office accommodation be- hind the protected façades. Few of the Fleet Street buildings are individually of any great architectural dis- tinction — that is not the point. The ones that stand out are the big, showy newspap- er buildings put up between the wars. There is the Daily Telegraph building, with its vulgar Portland stone facade in an Egyptian-cum-Art Deco style designed by Elcock & Sutcliffe but with Thomas Tait, a distinguished Scots architect, as consul- tant. And further down Fleet Street opposite Lutyens's Reuter's is the Daily Express, given, in deliberate and extreme contrast, a sleek modern skin of glass and black vitrolite over its reinforced concrete frame. The architects of this masterpiece were ostensibly the firm of Ellis & Clarke,

who specialised in newspaper buildings, but the real designer was the maverick engineer, Sir Owen Williams. The splendid `Deco' entrance hall, however — the only London rival to the skyscraper lobbies of New York and Chicago — was the work of Robert Atkinson.

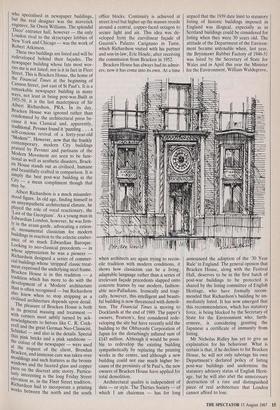

These two buildings are listed and will be redeveloped behind their façades. The newspaper building whose fate most wor- nes me is not listed; nor is it in fact in Fleet Street. This is Bracken House, the home of the Financial Times at the beginning of

i Cannon Street, just east of St Paul's. It is a remarkable newspaper building in many ways, not least in being post-war.Built in 1955-59, it is the last masterpiece of Sir Albert Richardson, PRA. In its day, Bracken House was ignored rather than condemned by the architectural press be- cause it was Classical and, apparently,

traditional. Pevsner found it `pnigling . a self-concious revival of a forty-year-old "Modern"'. However, now that the frankly contemporary, modern City buildings praised by Pevsner and partisans of the Modern Movement are seen to be func- tional as well as aesthetic disasters, Brack- en House stands out as civilised, humane and beautifully crafted in comparison. It is simply the best post-war building in the City — a mean compliment though that may be.

Albert Richardson is a much misunder- stood figure. In old age, finding himself in an unsympathetic architectural climate, he Played the role of vocal reactionary, the Last of the Georgians'. As a young man in Edwardian London, however, he was firm- ly in the avant-garde, advocating a ration- al, monumental classicism for modern buildings in reaction to the eclectic exuber- ance of so much Edwardian Baroque. Looking to neo-classical precedents — in whose appreciation he was a pioneer Richardson designed a series of commer- cial buildings whose 'stripped' classic treat- ment expressed the underlying steel frame. Bracken House is in this tradition — a tradition which has more to do with the development of a 'Modern' architecture than is often recognised — but Richardson also knew when to stop stripping as a civilised architecture depends upon detail.

The pleasure of Bracken House is both In its general massing and treatment — with corners most subtly turned by ack- nowledgments to heroes like C. R. Cock- erel( and the great German Neo-Classicist, Schinkel — and also in the details. Special thin pink bricks and a pink sandstone the colour of the newspaper — were used at the request of the client, Brendan Bracken, and immense care was taken over mouldings and such features as the bronze windows and the faceted glass and copper piers on the discreet attic storey. Particu- larly interesting is the long Friday Street elevation as, in the Fleet Street tradition, Richardson had to incorporate a printing works between the north and the south

office blocks. Continuity is achieved at street level but higher up the masses recede around a central, copper-faced octagon to secure light and air. This idea was de- veloped from the curvilinear facade of Guarini's Palazzo Carignano in Turin, which Richardson visited with his partner and son-in-law, Eric Houfe, after receiving the commission from Bracken in 1952.

Bracken House has always had its admir- ers; now it has come into its own. At a time

when architects are again trying to recon- cile tradition with modern conditions, it shows how classicism can be a living, adaptable language rather than a series of irrelevant façade precedents slapped onto concrete frames by our modern, fashion- able neo-Palladians. Ironically and tragi- cally, however, this intelligent and beauti- ful building is now threatened with demoli- tion. The Financial Times is moving to Docklands at the end of 1989. The paper's owners, Pearson's, first considered rede- veloping the site but have recently sold the building to the Ohbayashi Corporation of Japan for the disturbingly inflated sum of £143 million. Although it would be possi- ble to redevelop the existing building sympathetically by replacing the printing works in the centre, and although a new building could not rise much higher be- cause of the proximity of St Paul's, the new owners of Bracken House have applied for total demolition.

Architectural quality is independent of date — or style. The Thirties Society — of which I am chairman — has for long argued that the 1939 date limit to statutory listing of historic buildings imposed in England was illogical, especially as in Scotland buildings could be considered for listing when they were 30 years old. The attitude of the Department of the Environ- ment became untenable when, last year, the Brynmawr Rubber Factory of 1946-51 was listed by the Secretary of State for Wales and in April this year the Minister for the Environment, William Waldegrave,

announced the adoption of the '30 Year Rule' in England. The general opinion that Bracken House, along with the Festival Hall, deserves to be in the first batch of post-war buildings to be protected is shared by the listing committee of English Heritage, who have formally recom- mended that Richardson's building be im- mediately listed. It has now emerged that this recommendation, which has statutory force, is being blocked by the Secretary of State for the Environment who, furth- ermore, is considering granting the Japanese a certificate of immunity from listing. Mr Nicholas Ridley has yet to give an explanation for his behaviour. What is certain is that, if he declines to list Bracken House, he will not only sabotage his own Department's declared policy of listing post-war buildings and undermine the statutory advisory status of English Herit- age, but he will also abet the unnecessary destruction of a rare and distinguished piece of real architecture that London cannot afford to lose.

Previous page

Previous page