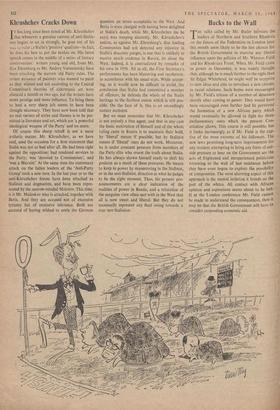

Khrushchev Cracks Down

T has long since been noted of Mr. Khrushchev Ithat whenever a genuine current of anti-Stalin- ism begins to set in strongly, he goes out of his cu rurer to Stalin's 'positive' qualities—in fact, he does his best to put the brakes on. His latest speech comes in the middle of a series of literary controversies: writers young and old, from Mr. Ilya Ehrenburg to Mr. Andrey Voznesensky have been attacking the narrow old Party rules. The minor nuisance of painters who wanted to paint as they wished and not according to the Central Committee's theories of aldermanic art were silenced a month or two ago, but the writers have more prestige and more influence. To bring them to heel a very sharp jolt seems to have been thought necessary. They have now been told that no real variety of styles and themes is to be per- mitted in literature and art, which are 'a powerful ideological weapon of the Party' and no more.

Of course this sharp rebuff is not a mere aesthetic matter. Mr. Khrushchev, as we have said, used the occasion for a firm statement that Stalin was not so bad after all. He had been right against the opposition; had rendered services to the Party; was 'devoted to Communism'; and `was a Marxist.' At the same time the customary attack on the fallen leaders of the 'Anti-Party Group' took a new turn. In the last year or so the anti-Khrushchev forces have been attacked as Stalinist and dogmatists, and have been repre- sented by the narrow-minded Molotov. This time, it is Mr. Malenkov who is attacked, together with Beria. And they are accused not of excessive tyranny but of excessive tolerance. Both are accused of having wished to settle the German question on terms acceptable to the West. And Beria is even charged with having been delighted at Stalin's death, while Mr. Khrushchev (as he says) was weeping sincerely. Mr. Khrushchev's notion, as against Mr. Ehrenburg's, that leading Communists had not detected any injustice in Stalin's draconic purges, is one that is unlikely to receive much credence in Russia, let alone the West. Indeed, it is contradicted by remarks of his own in 1956. All in all, the First Secretary's performance has been blustering and incoherent, in accordance with his usual style, While accept- ing, as it would now be difficult to avoid, the conclusion that Stalin had committed a number of offences, he defends the whole of the Stalin heritage to the furthest extent which is still pos- sible. On the face of it, this is an exceedingly sinister outburst.

But we must remember that Mr. Khrushchev is not entirely a free agent, and that in any case the basic motivation of himself and of the whole ruling caste in Russia is to maintain their hold, by 'liberal' means if possible, but by Stalinist means if 'liberal' ones do not work. Moreover, he is under constant pressure from members of the Party elite who resent the truth about Stalin. He has always shown himself ready to shift his position as a result of these pressures. He means to keep in power by manoeuvring in the Stalinist, or in the anti-Stalinist, direction at what he judges to be the right moment. Thus, his present pro- nouncements are a clear indication of the realities of power in Russia, and a refutation of the sanguine view often met with in the West that all is now sweet and liberal. But they do not necessarily represent any final swing towards a true neo-Stalinism.

Previous page

Previous page