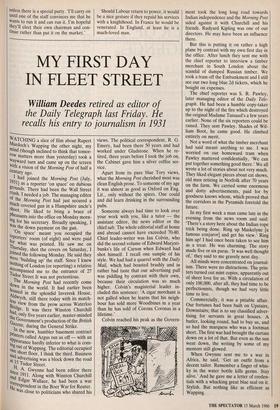

MY FIRST DAY IN FLEET STREET

William Deedes retired as editor of

the Daily Telegraph last Friday. He recalls his entry to journalism in 1931

WATCHING a slice of film about Rupert Murdoch's Wapping the other night, my mind (though inclined to think that tomor- row matters more than yesterday) took a wayward turn and came up on the screen With a vision of the Morning Post of half a Century ago. I had joined the Morning Post (July, 1931) as a reporter 'on space' on dubious grounds. There had been the Wall Street Crush. I needed a job. The managing editor of the Morning Post had just secured a much coveted gun in a Hampshire uncle's Shoot. He liked to bring a brace of Pheasants into the office on Monday morn- ing for his secretary. Broadly speaking, I Was the down payment on the gun. 'On space' meant you occupied the reporters room (of eight) and were paid ,,,,u3r what was printed. He saw me on nursday, shot the covers on Saturday, I Joined the following Monday. He said they Were 'building up' the staff. Since I knew nothing of London (or reporting) a relative accompanied me to the entrance of 27 Tudor udor Street. It was not pretentious. , The Morning Post had recently come down in the world. It had earlier been housed in the splendid Inveresk House, 1MdwYeli, still there today with its match- view from the prow across Waterloo :!ridge. It was there Winston Churchill ad, only five years earlier, master-minded the Government's production of the British ulizette, during the General Strike. 1fl the new, humbler basement contract Printers called Argus ran us off — with an PPearance hardly inferior to what is com- 418 out of Wapping. The editorial occupied one short floor, I think the third. Business and advertising was a block down the road at 15 Tudor Street. i H. A. Gwynne had been editor there s‘li ce 1911. Along with Winston Churchill and Edgar Wallace, he had been a war HrresPondent in the Boer War for Reuter. e was close to politicians who shared his views. The political correspondent, R. G. Emery, had been there 50 years and had worked under Gladstone. When he re- tired, three years before I took the job on, the Cabinet gave him a silver coffee ser- vice.

Apart from its pure blue Tory views, what the Morning Post cherished most was clean English prose. To someone of my age it was almost as good as Oxford on Eng. Lit., only without the spires. One could and did learn drinking in the surrounding pubs. Someone always had time to look over your work with you, like a tutor — the assistant editor, the news editor or the chief sub. The whole editorial staff at home and abroad cannot have exceeded 70-80. Chief leader-writer was Ian Colvin, who did the second volume of Edward Marjori- banks's life of Carson when Edward had shot himself. I recall one sample of his style. We had had a quarrel with the Daily Mail, which had boasted brashly and in rather bad taste that our advertising pull was piddling by contrast with their own, because their circulation was so much higher. Colvin's magisterial leader in- cluded this sentence: 'A cigar merchant is not galled when he learns that his neigh- bour has sold more Woodbines in a year than he has sold of Corona Coronas in a lifetime.'

Colvin reached his peak as the Govern- ment took the long long road towards Indian independence and the Morning Post sided against it with Churchill and his friends. Rudyard Kipling was one of our directors. He may have been an influence there.

But this is putting it on rather a high plane by contrast with my own first day in the office. After lunch they sent me with the chief reporter to interview a timber merchant in South London about the scandal of dumped Russian timber. We took a tram off the Embankment and I still see our two long blue 2d tickets, which he bought on expenses.

The chief reporter was S. R. Pawley, later managing editor of the Daily Tele- graph. He had been a humble copy-taker up to the night of the fire which destroyed the original Madame Tussaud's a few years earlier. None of the six reporters could be raised. They sent Pawley. Shades of Wil- liam Boot, he came good. He climbed entirely on merit.

Not a word of what the timber merchant had said meant anything to me. I was worried on our homeward tram when Pawley muttered confidentially, 'We can put together something good there.' We all wrote a lot of stories about not very much. They liked elegant pieces about cat shows, old men retiring in Norfolk after 70 years on the farm. We carried some enormous and dotty advertisements, paid for by goodness knows whom, which proved that the corridors in the Pyramids foretold the future.

In my first week a man came late in the evening from the news room and said: 'There's a story here about the Indian rope trick being done. Ring up Maskelyne [a famous conjuror] and get his view.' Ring him up! I had once been taken to see him as a treat. He was charming. The story made five or six paras. 'It was well thought of,' they said to me gravely next day.

All minds were concentrated on journal- ism. There were no distractions. The prin- ters turned out mint copies, apparently out of sheer love for us. With a circulation of only 100,000, after all, they had time to be perfectionists, though we had very little time to live.

Commercially, it was a pitiable affair. Our fortunes had been built on Upstairs, Downstairs; that is to say classified adver- tising for servants in great houses. A butler, looking round, had to buy us, and so had the marquess who was a footman short. The first war had brought the curtain down on a lot of that. But even as the sun went down, the writing by some of my mentors still glowed.

When Gwynne sent me to a war in Africa, he said, 'Get an outfit from a decent tailor. Remember a finger of whis- ky in the water bottle kills germs. Stay alive.' And he gave me a letter of creden- tials with a whacking great blue seal on it. Stylish. But nothing like as efficient as Wapping.

Previous page

Previous page