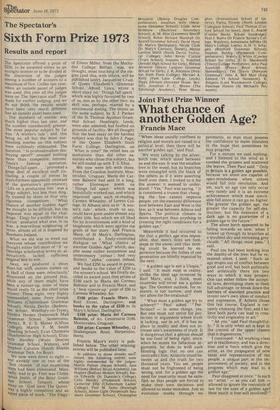

What chance of

another Golden Age?

Francis Mace

"When ideas usually confined to religion and morals are raised to a political level, then there will be another golden age," said Paul.

We were talking by the silverbirch tree, which stood between us and the sun. It was the smallest tree in the wood, but its branches were entangled with the black of the others as if it were asserting itself over them. I looked to it for the answer; it seemed to understand. "Yes," Paul was saying, " it is considered a truism that changing the law cannot improve people, yet the essential difference now between East and West is the law, as it was between Athens and Sparta. The political climate is more important than anything in creating the right conditions for a golden age."

MeanWhile it had occurred to me that a perfect age was impos sible, that men's lives are foot steps in the snow, and that nothing could be learned by ex perience because the follies of one generation are blindly repeated by the next.

"A golden age is not a Utopia," I said. "It must exist in reality, unlike the ideal age invented by Karl Marx; and, I think, most countries will never see a golden age. The German outlook, for instance, is too narrow, and does not allow for the irrational."

" What must a golden age try to achieve?" Paul asked. "Perfection? — in some things, yes. But one must not strive for perfection in arguments where truth is lacking, nor in art, if it has no place in reality and does not increase one's awareness of truth. It is dangerous that a genius should be too fond of being right, since, when he states his fallacious arguments, he does so with such blinding logic that no one can contradict him; Aristotle stood between us and the truth for two thousand years. You see, people must not be frightened of being wrong, and, for a golden age the need for insecurity must be satisfied, so that people are forced to make their own decisions and allowed to make mistakes. Just as evolution works through ex periments, so man must, possess the confidence to make mistakes in the hope that sometimes he may progress."

For a minute we said nothing, and I listened to the wind as it combed the grasses and scattered the leaves. Then Paul said: "Only in Britain is a golden age possible, because we alone are capable of open-mindedness when others would fall into revolution. And yet, such an age can only occur very rarely and it is an extreme achievement which must inevitable fall since it can go no higher. The greater the golden age, the greater the capacity for self-destruction; but the existence of a dark age is no guarantee of a golden age in the future."

The silver birch appeared to be falling towards us now, when I looked up through its branches at a troubled sky and retreating grey clouds. " All things must pass," l said. • Paul too had been looking into the depths of the tree; but he remained silent. I said: "Such an age erupts out of conflict between good and evil, but both politically and artistically there are two ways in which it may prosper. One can either follow the accepted laws, developing them to their full advantage, or break down the barriers of standard practice and invent one's own ideas of conduct and expression. If Athens chose this last course, England is certainly choosing the first; and I believe both parts can lead to creativity and originality in art."

" Ah yes," said Paul thoughtfully. "It is only when art is kept in the control of the upper classes that it degenerates."

I continued: "All working-class art is reactionary, and has a direc tion and a force which give the artist, as the propagator of new ideas and representative of the people, a unique part in the improvement of society, and in the progress which may lead to a golden age."

Paul disagreed at once." Is such an ' artist ' — as you call him — allowed to ignore the restraints of law for the sake of a golden age? How much is free-will involved?"

Previous page

Previous page