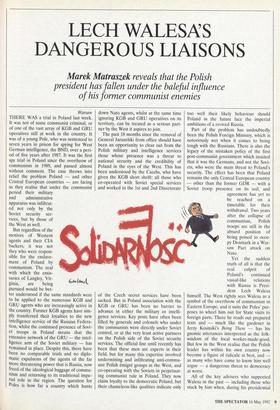

LECH WALESAS DANGEROUS LIAISONS

Marek Matraszek reveals that the Polish president has fallen under the baleful influence of his former communist enemies

THERE WAS a trial in Poland last week.

It was not of some communist criminal, or of one of the vast array of KGB and GRU operatives still at work in the country. It was of a young Pole, who was sentenced to seven years in prison for spying for West German intelligence, the BND, over a peri- od of five years after 1987. It was the first spy trial in Poland since the overthrow of communism in 1989, and passed almost without comment. The case throws into relief the problem Poland — and other Central European countries — are facing as they realise that under the communist period their military and administrative apparatus was infiltrat- ed not only by the Soviet security ser- vices, but by those of the West as well.

But regardless of the motives of Western agents and their CIA backers, it was not they who were respon- sible for the enslave- ment of Poland by communism. The zeal with which the emis- saries of Langley, Vir- ginia, are being pursued would be bet- ter understood if the same standards were to be applied to the numerous KGB and GRU agents who are increasingly active in the country. Former KGB agents have sim- ply transferred their loyalties to the new intelligence service of the Russian Federa- tion, whilst the continued presence of Sovi- et troops in Poland means that the extensive network of the GRU — the intel- ligence arm of the Soviet military — has remained in place. Despite this, there have been no comparable trials and no diplo- matic expulsions of the agents of the far more threatening power that is Russia, now freed of the ideological baggage of commu- nism and returning to its traditional impe- rial role in the region. The question for Poles is how far a country which hunts down Nato agents, whilst at the same time ignoring KGB and GRU operatives on its territory, can be treated as a serious part- ner by the West it aspires to join.

The past 18 months since the removal of General Jaruzelski from office should have been an opportunity to clear out from the Polish military and intelligence services those whose presence was a threat to national security and the credibility of Poland in the eyes of the West. This has been understood by the Czechs, who have given the KGB short shrift: all those who co-operated with Soviet special services and worked in the 1st and 2nd Directorate of the Czech secret services have been sacked. But in Poland association with the KGB or GRU has been no barrier to advance in either the military or intelli- gence services. Key posts have often been filled by generals and colonels who under the communists were directly under Soviet control, or at the very least active partners on the Polish side of the Soviet security services. The official line until recently has been that these men are experts in their field, but for many this expertise involved undermining and infiltrating anti-commu- nist Polish émigré groups in the West, and co-operating with the Soviets in perpetuat- ing communist rule in Poland. They now claim loyalty to the democratic Poland, but their chameleon-like qualities indicate only too well their likely behaviour should Poland in the future face the imperial ambitions of a revived Russia.

Part of the problem has undoubtedly been the Polish Foreign Ministry, which is notoriously wet when it comes to being tough with the Russians. There is also the legacy of the mistaken policy of the first post-communist government which insisted that it was the Germans, and not the Sovi- ets, who were the main threat to Poland's security. The effect has been that Poland remains the only Central European country — other than the former GDR — with a Soviet troop presence on its soil, and agreement has yet to be reached on a timetable for their withdrawal. Two years after the collapse of communism, Polish troops are still in the absurd position of being poised to occu- py Denmark in a War- saw Pact attack on Nato.

Yet the saddest truth of all is that the real culprit of Poland's continued Eastern Europe, and it suits the Poles' pur- poses to wheel him out for State visits to foreign parts. There he reads out prepared

texts and — much like the gardener in Jerzy Kosinski's Being There — has his

gnomic utterances interpreted as the folk- wisdom of the local worker-made-good. But few in the West realise that the Polish

leader has within his own country now become a figure of ridicule at best, and — as many who have come to know him well argue — a dangerous threat to democracy at worst.

All of the key advisers who supported Walesa in the past — including those who stuck by him when, during his presidential campaign, he was the target of vicious attack by the country's intelligentsia — have deserted him, horrified at the work- ings of the presidential palace. More importantly, many have been alienated by the way Walesa has reneged on his cam- paign image of a patriotic anti-communist. Instead of using his political talents to help the reform of the country, Walesa has expended his energies in the only way he knows how, that of maintaining and build- ing his power. Lacking his own political party, he has been able to achieve this only through attacking any politician who might challenge his authority. Now he is alone, reliant on his inner circle of press spokesman, confessor, and former chauf- feur Mieczyslaw Wachowski. The result has been that in his search for support he has turned to the two political forces which one would least expect: communist generals in the army, and the former nomenklatura aparatchiks making good in the new mar- ket economy.

Ever since coming to power, Walesa has sought to gain control over the armed forces beyond his constitutional powers. The tragedy is that he has sought to do so by relying on those who have the weakest spines and are the most likely yes-men: those military officers particularly compro- mised by their loyalty to the communist system and Soviet intelligence services. Instead of taking advantage of his presi- dency to clear out placemen and potential traitors, he has petrified the old communist structures in the military, and if anything strengthened them.

There is a school of thought which justi- fies Walesa's actions by placing the man in the category of a realpolitiker who judges the balance of forces and works pragmati- cally within them in the nation's interests. But in fact the effects of his moves have been disastrous. Early in 1991, Walesa became convinced that he could obtain the loyalty of the army not by clearing out the old guard — as his closest advisers then tried to convince him — but by relying on the old commmunist elite in the army and intelligence services. That meant keeping in place Admiral Piotr Kolodziejczyk as Minister of Defence — an old communist and Jaruzelski loyalist — and promoting to the post of chief of military counter-intelli- gence Czeslaw Wawrzyniak, Kolod- ziejczyk's own chef de cabinet who had been in charge of naval counter-intelligence on the Baltic coast, where he had been active in combating the Solidarity underground. At the same time, Walesa set about attempting to woo army officers through his National Security Office, which he has now expanded so that its departments mir- ror those of the Defence Ministry. As the communists before him did through Party cells, Walesa has sought to control the army through a network of loyalists, whilst the Defence Ministry becomes an empty shell, responsible before Parliament for policies it cannot influence.

Following their nominations, both Kolodziejczyk and Wawrzyniak acted to block any moves by Poland towards Nato, arguing for the need for continued ties with the Soviet Union and, following its col- lapse, with the Russian Federation. For this reason, Walesa backed Gorbachev's attempts to keep the Soviet Union together to the very end, openly snubbing Yeltsin. Worse still, at the time of the Moscow coup Walesa was on the point of sending a letter of congratulation to Gennady Yanayev, the putsch leader, underlining Poland's willing- ness to co-operate with the new Soviet authorities. Only the personal intervention of the then Prime Minister Bielecki dis- suaded Walesa from joining Gaddafi, Cas- tro and Arafat in recognition of the fall of Gorbachev. Poland's best-informed politi- cians argue that all this is no coincidence: they say that Western intelligence services have evidence of links between the Russian security services and Wachowski, through whom the long-run interests of the Rus- sians in isolating Poland from the West are being effected. `We did not foresee the influence of Wachowski,' admits Jaroslaw 'Of course I have standards, Benwell. I've got double standards.' Kaczynski, one of Poland's brightest politi- cians, bemoaning his decision to support Walesa becoming president.

Only slightly less disturbing is the fact that under Wawrzyniak military counter- intelligence became a key source of politi- cal information for Walesa. The link here is again Wachowski, who many suspect of having personal links with Wawrzyniak going back some years, and who acted as Wawrzyniak's patron in the Belvedere Palace. Through Wachowski, Walesa received from Wawrzyniak details of the private lives of Poland's leading politicians and transcripts of their private conversa- tions. When Wawrzyniak was finally sacked last month, the immediate reason was that listening devices had been discovered in the private offices of the Prime Minister. Wawrzyniak was the culprit. His departure came last month in circumstances worthy of the best spy thriller: in order to prevent him from destroying evidence of his activi- ties, he was summoned to the Defence Ministry under a false pretext, and under observation from Poland's elite anti-terror- ist units relieved of his duties and summari- ly ejected from the premises. Walesa and Wachowski, on a state visit in Germany at the time, were no less astonished to find that the military intelligence services were no longer at their disposal in their intrigues against Poland's parliamentarians.

Walesa and Wachowski know that it is not enough to control the army in order to control Poland. That can only be done by influencing the economy. Even after almost three years of reform, the economy remains a hybrid, where, through corrup- tion and old communist party links, those who have information and access to the right people can make their fortunes. The key is the banking system, which remains largely state-owned and is a source of financial power and patronage: here dirty money is laundered, taxes evaded, and fraudulent foreign currency deals made. Over the past year, the former chaffeur Wachowski has extended his influence into this sector, and two months ago Walesa successfully bullied parliament into accept- ing an incompetent and pliable nominee as President of the National Bank. Wachows- ki has his own financial interests: there is scandalous talk of his having attempted to swindle a Polish-American out of $50,000. Now he is now turning his talents to giving orders to the new National Bank President on matters far removed from official finan- cial policy.

As a result of this and other scandals, Polish politicians have begun to say openly what they have thought for some time: that in the face of continuing political chaos Walesa is manoeuvring to obtain uncon- trolled powers, at first by pressure on par- liament, and should that fail, by more direct means. That requires the loyalty of the army and the security forces, as well as a base of support among the country's financial elite. It was partly to scupper these plans, and to ensure the restoration of governmental control over the armed forces and intelli- gence services, that Prime Minister Olszewski appointed Jan Parys as Defence Minister in January. Slightly-built, with owlish glasses and a penchant for sensible waistcoats, Parys seems an unlikely candi- date to take on Walesa. But he is admirably versed in strategic and defence studies, and is one of the few Polish politi- cians who openly speaks of national hon- our and patriotic duty. That makes a change from the wooden techno-speak of Foreign Ministry hacks, and a marked con- trast to the woolly liberal platitudes of Poland's intellectual elite.

One of Parys's first acts was to investi- gate military and intelligence officers for links with the post-Soviet security services, which resulted in the immediate sackings of Kolodziejczyk, Wawrzyniak and a host of top-ranking generals, followed by their replacement by younger officers. Walesa's response has been to offer jobs to many of the sacked men in his National Security Office, followed by panic-stricken moves to engineer Parys's dismissal. That has merely underlined the fact that the political argu- ment in Poland is no longer over policy in a democratic framework, but about how to rescue democracy from the increasingly desperate moves of Walesa himself. With the Polish government tottering on the brink of collapse, and parliament impotent, that is now a real danger.

The Central European countries are rightly trying to convince Nato of the need to bring them into the Western orbit before they are sucked in by future post-Soviet crises. But the West will do nothing if the Poles fail to clear their military and intelli- gence networks of those who, although loyal now, would be unreliable in times of crisis. As long as this continues, the hand of those in the US State Department who wish to lump the Central Europeans in with the post-Soviet republics, and deny them closer relations with Nato, will be strengthened. That would condemn Poland to a further period of subordination to the Russian interests from which she has his- torically sought to free herself. The Polish government, through Parys, has tried to follow the security policy changes pursued in Czechoslovakia and Hungary, and has accepted that the main danger to its national security lies in the still-existing KGB and GRU networks inside and out- side the administration. It is sad to admit that the main obstacle to success in this endeavour is the Polish President, who has done so much for his country in the past. But just as it is because of Walesa that many have remained silent, so it is because of Poland that it is now time to speak the truth.

Marek Matraszek is the Warsaw Director of the Jagiellonian Foundation. This article is written in a personal capacity.

Previous page

Previous page